Aspiring filmmakers attend film school where they become proficient with their craft. It is also important for students in these schools to study the history of cinema so that one can understand their horizon of the possibilities of the art and through this, become one of the greats.

1. A Trip to the Moon (Dir. Georges Méliès, 1902)

At the dawn of cinema, filmmakers didn’t know what the medium was fully capable of. As such, they experimented in cinema based on their skills within other art forms. One such experimenter was magician Georges Méliès who saw cinema as an illusion and dream. In 1902, after making around 100 films, Méliès created cinema’s first masterpiece: A Trip to the Moon.

Inspired by the works of Jules Verne, A Trip to the Moon tells the story of a group of astronomers who voyage to the moon and discover the strange inhabitants of it. After being placed in danger the astronomers escape and land in an ocean on Earth and are treated as heroes.

A Trip to the Moon is a time capsule for the mystery and wonderment that surrounded space. But more importantly, it is an early pioneer in visual effects and an early example of the dreamlike possibilities cinema has by presenting a fantasy that lived in the heart and mind of its director.

2. The General (Dir. Buster Keaton and Clyde Bruckman, 1926)

By the 1920s, cinema had become a commercial art that had gone beyond its vaudevillian roots and discovered itself as a visual storytelling medium. In becoming commercial, the star system was slowly becoming apparent, with actors such as Harold Lloyd, Charlie Chaplin, and Buster Keaton becoming big selling points in regards to the film.

Perhaps the most innovative of the three aforementioned individuals was Buster Keaton, whose acting roles were defined by the stunt coordination and slapstick humor, and therefore made him cinema’s first action star.

The General is Buster Keaton at his finest and perhaps his most influential and most iconic film. It tells the story of a train conductor fighting for the Confederate Army during the American Civil War. The General remains one of the funniest films ever made, showing slapstick and general physical humor at its finest. Looking at it from a technical perspective, it is also one of the most visually inventive films of all time because of Keaton’s use of framing.

It is an essential viewing for those interested in cinema for reasons of witnessing some of the finest stunt coordination and, more importantly, to understand a popular style of filmmaking during the silent era.

3. Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (Dir. F.W. Murnau, 1927)

F.W. Murnau is one of the most visual directors of all time. Which is why, perhaps, he loathed using title cards in his movies, all of which were silent films. He was also a leader of German Expressionism, an artistic movement that occurred as a response to World War I and was defined by its obsession with urban life, use of Chiaroscuro lighting, and symbolically distorted art design.

With his 1927 film, Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans, F.W. Murnau became one of the first mainstream filmmakers to experiment with the sound-on-film system, which refers to capturing sound physically on celluloid and continues to be used to this day on some films. For Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans, Murnau used the system as a means to create minor sound effects, but more importantly to have a definitive score attached to the film.

Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans is one of the finest examples of visual storytelling. For this reason, it is important for all film students to see this film. But it is also a great movie that is still as enjoyable as it was when it was first released nearly 90 years ago.

4. The Passion of Jeanne d’Arc (Dir. Carl Th. Dreyer, 1928)

Like with all artistic mediums, cinema has been influenced greatly by mythos, religion, and history. One of the most popular of these types to be told in cinema is the story of Jeanne d’Arc, the teenage girl sent by God to lead the French to victory in the Hundred Years’ War.

This story has been told in cinema from as early as 1900 when Georges Méliès depicted her execution in his film, Jeanne d’Arc. In 1928, Danish filmmaker, Carl Th. Dreyer created the definitive cinematic version of the story in The Passion of Jeanne d’Arc.

The Passion of Jeanne d’Arc is the cinema at its very best; Carl Th. Dreyer’s film examines Jeanne d’Arc during her trial after being sold out by her people to the British. As with F.W. Murnau’s Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans, The Passion of Jeanne d’Arc is a great example of visual story telling.

Dreyer famously utilized only close-ups and medium shots for his film, creating a cinematic language that exists primarily in facial expressions of his actors, and thus giving the audience an intimate relationship with each of the characters in the film. With his camera, Dreyer studies each of his characters and shows the pain that lies beneath all of them. The use of close-ups also gives a claustrophobic atmosphere, which compliments the subject of the film- preparing for a death.

Watching a film like The Passion of Jeanne d’Arc makes one wish that more films were as intimate and up close and personal as this one. For this reason, film schools everywhere should be showing this film. It is truly a masterpiece of a movie!

5. Man With a Movie Camera (Dir. Dziga Vertov, 1929)

Dziga Vertov begins Man With a Movie Camera by informing his audience that there are neither actors nor story in his film. Instead what is seen is 68 minute long dictionary of cinematic techniques with everything from parallel to continuity editing being utilized in post and every type of shot imaginable being used during production.

Beyond being a dictionary for cinematic techniques, Man With a Movie Camera should also be studied as a propaganda film, as it is one of the earliest examples of this genre. Dziga Vertov was a Russian filmmaker alive during the rise of Communism and he, along with his fellow Russian filmmakers Sergei Eisenstein and Aleksandr Medvedkin, used cinema as a means to promote their political ideology.

Throughout Man With a Movie Camera, Dziga Vertov emphasizes rapid-fire editing while showing different machines working together to quickly create an effective and long lasting product and the potential to propel technology together, by working as a machine. This visual imagery acts as a metaphor for the potential that a communist state could have for Russia, a country that had long been behind the modern nations.

One thing that Dziga Vertov definitely pushed into the forefront of cinema through Man with a Movie Camera was the use of montage. Prior to this film, montage was not an apparent technique within the cinematic community. After this films release, it became a common technique for filmmakers to use and retains its status to this day.

6. Un Chien Andalou (Dir. Luis Bunuel, 1929)

Surrealism was a movement that began in the 1920s as a follow up to Dada. The goal in Surrealism was to “resolve the previously contradictory conditions of dream and reality.” Its leaders were poet André Breton and painter Salvador Dalí. In 1929, Dalí teamed up with filmmaker, Luis Bunuel to create the very first Surrealist film.

The result was Un Chien Andalou, a film devoid of plot or meaning whose sole goal was to create a dream for the viewer to experience. Unlike Georges Méliès, who saw dreams as fantasies with a logical story attached, Bunuel saw them as fragmented observations of the subconscious, showing the dark, inner desires that we as humans want.

The film is a landmark in free form storytelling and avant-garde art. It is also a great example of the possibilities that filmmaking has in terms of mood and atmosphere. It remains one of the most influential films to this day and is a must watch for anyone interested in an alternative style of filmmaking, over the traditional story based one.

7. L’Atalante (Dir. Jean Vigo, 1934)

Jean Vigo made four films before he tragically died from tuberculosis at the age of 29 in 1934. While all four films are worth seeking out, the one that all film students need to watch is his final film: L’Atalante.

L’Atalante is a beautiful example of the human condition being portrayed through cinema. Each character is treated as fleshed out human beings, who are not purely good or bad, making it easy to sympathize with each one of them. The situations are presented in un-objective manner, so that audience members can look at it from a pure third perspective and therefore make the characters that much more real and honest.

It’s a shame that Jean Vigo died as young as he did. But what he left was a legacy of influential and important movies that continue to be studied to this day.

8. Citizen Kane (Dir. Orson Welles, 1941)

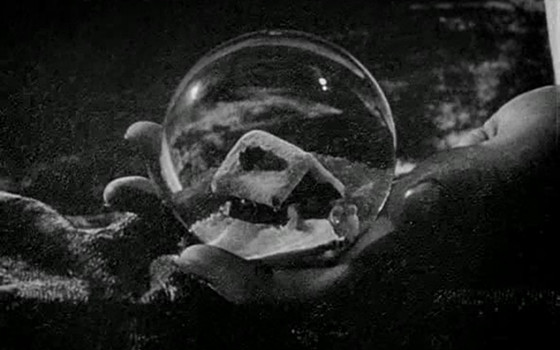

Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane is evidence that it is possible to deserve a cliché. Unlike other films on this list, Welles’ film does not need not much description, as it has a legacy of being notoriously voted as the greatest film of all time- which that too it is deserving of.

Not only is it a great story complimented by some of the finest usage of deep focus photography (that is, in it of itself, innovative and continuously influential), an incredible noir like use of shadows, and features one of the greatest ensembles ever committed to celluloid, it is the film that single handedly changed visual storytelling.

Prior to this film’s release, films were largely shot using either static medium close up or static wide shots and actions and character were presented largely through dialogue. But this film changed that forever. After it’s release, filmmakers started to use tracking shots in the way that Welles did here. They also started using more low and high angle shots to define character and allowed moments of silence to speak for themselves, much like the rest of this film.

If cinema’s dictionary is Man With a Movie Camera, then Citizen Kane is its Hamlet and Orson Welles its Shakespeare.