Since the gangly Count Orlock crept up those stairs in F.W. Murnau’s Nosferatu (1922), horror cinema has relied on stylistic efforts to cause terror in its audience. Contrasts between light and darkness, depiction of true evil, menacing pursuits through confined spaces and stories that convey the supernatural and abnormal have been staples of horror classics since the dawn of cinema.

However, over the decades since Murnau’s feature length horror classic, other works of cinema have used these techniques effectively in non-horror films. Sometimes a dramatic suggestion in a non-horror scene will garner the same reaction as a jump scare in a slasher film, sometimes an unseen (or in many cases non-physical) presence is scarier than a machete-wielding madman ready to emaciate a hapless victim.

This list is focused on those films that convey an air of horror while not being classified as horror films themselves. The selections for this list cover a wide range of genres, some have been put in the suspense category while others creep into dark comedy territory. Each selection contains a key scene or sometimes the entire film works under horror’s guise, lending an effective reading and reaction.

The list has been divided into four parts that fall between horror film and non-horror represented by three film each.

The first section, “real life” horror, is basically a look into the lives of people where the main terrorizing element is what surrounds us in everyday life and the effect it has on families and society. Although the villain is almost always unseen and sometimes not even a physical presence, the choices in this section have obvious approaches akin to horror films ranging from slasher movies to ghost stories.

The second area focuses on substance abuse, where the effects of drugs or alcohol leads to an emotional or psychological downfall for the characters. This area contains heavy imagery-focused horror tactics that are reminiscent of the famous “creature horrors” of yore and psychological horror films of the modern age.

The third area of focus is on “what if” scenarios where science-fiction and horror can meet, yet the science-fiction and supernatural are so toned down that the viewer could indeed be watching a news report or a conspiracy account that has enough truth in it to creep the viewer out like scary campfire story would.

The final area focuses on the “suspenseful into scary.” These selections are some of the more obvious choices yet are effective enough that some of them have been deemed horror films by fans and critics despite not being classified as such. They are so heavily influenced by horror that they bridge the gap between horror and thriller and sometimes even step beyond terror via more realistic actions and minimal effects.

A note on spoilers: There are indeed some crucial scenes that will be talked about in this article. Therefore this list contains spoilers.

1. The Seventh Continent (1989) – Michael Haneke

The horrors of the mundanity of real life are encapsulated in Austrian director Michael Haneke’s first cinematic effort. Set over the course of three years in Austria in the late-1980s, the film looks into the lives of three family members: Georg (Dieter Berner), the patriarch of the family; Anna (Birgit Doll), the mother; and Evi (Leni Tanzer), the young daughter.

Each character represents an area of society that follows the boring tradition of wake up, go to work/school, come home, eat dinner, watch TV, go to sleep. The looming discomforting knowledge of high debts and mortgage payments is ever present and the futility of the constant routines of life begins to affect the family in different ways, Georg becomes cold and emotionless, Anna becomes sardonic, and Evi takes up pathological lying as a cry for help.

Inspired by a real-life event where a family committed suicide, Michael Haneke employs standard horror tactics throughout the film by using long static takes of boring routines such as making breakfast and getting ready for work. It isn’t until an hour into the film where the horrors of boredom become intermingled with destruction. Georg buys a bunch of tools and goes with his wife to take out their life savings, telling the banker that they plan to leave for Australia.

The family then begins systematically gutting their house and destroying everything they own. One would think this would be a liberating experience but Haneke instead has the family perform these actions with the same mindless calculation as getting dressed for work or making breakfast.

The Seventh Continent works as a horror film due to its gradual revelation of what will happen by the end of the film. Basing his story in fact, Haneke crafts a film about a family with a “dreadful secret” that does not answer questions but rather has the audience piece the horrifying conclusion together through the film’s montage sequences.

Much like Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining (1980), it is a slow-boil into darkness. Haneke instead opts for a collective suicide rather than an axe-wielding madman stalking his family through a house and murdering them. Regardless, the unraveling of this plot device is just as scary as any horror thriller.

Haneke knew he would make his film cause terror and disgust in his audience while making the film, particularly during the family’s descent into destruction. In a two-minute long closeup shot of a toilet bowl, Georg flushes thousands of dollars in a jarring fashion. Haneke wanted to show that an audience would find a man flushing his life savings literally down the toilet would prove more disturbing than a family collectively killing their daughter, then themselves. With a looming sense of death and the creepy image of an unobtainable Australian dream life, The Seventh Continent is a jarring and horrific experience into real life problems.

2. Flandres (2006) – Bruno Dumont

In the current decade where the main news headlines cover the War on Terror, a whole slew of war and anti-war films have emerged such as Jarhead and American Sniper. However, these examples, although illustrating the mindlessness of war and its effect on the human psyche, are primarily focused on valor and heroism.

As atrocious as the violence is in these films, they do not have the horror vibe. Bruno Dumont expertly weaves war film with a taste of horror in his fourth film Flandres, where the characters clearly cross the threshold into evil while trying to survive. All the while Dumont’s insistence on realism keeps the horror aspects subtle enough to keep them from exploiting the effectiveness of the film.

The film follows André Demester (Samuel Boidin), a slow-witted French farmer who enlists in the armed forces to fight in an unnamed Middle Eastern country. After a brief scene of soldier camaraderie, he is thrust into the heart of darkness and wanders through the desert with his platoon unsafe and uncertain of his survival.

Back at home, Demester’s girlfriend/sexual partner Barbe (Adélaïde Leroux) mirrors Demester’s pains and sufferings through sheer boredom until she descends into madness. The film alternates perspectives, contrasting the gold hues of the Middle Eastern deserts with the cold blues of the European countryside.

Although this is primarily an anti-war film, it works as a horror due to its randomness of violence. In most war films, attacks are calculated and planned out, in this film the death springs out of nowhere and no character (including Demester) is safe from being killed.

Like the crew in Alien (1979) the soldiers are picked off one by one and begin squabbling amongst themselves, some of them even abandon their troop out of disgust or fear, a common horror tactic of “splitting up” when in danger. Dumont’s use of non-actors is also a great and effective way to evoke terror as none of the characters in the film is associated with a certain celebrity, making their deaths all the more shocking and tragic.

However, despite the audience’s association with the soldiers in the film, Dumont blurs the line between heroes and villains as he does not portray the Middle Easterns as the savage “Other,” but instead questions the heroism of the Europeans on foreign soil. In a truly horrifying scene, Demester and his men find a guard outpost manned by a female guerrilla soldier.

Outnumbered, the female soldier struggles and is eventually gang raped by the platoon. Demester, who at first is an observer, crosses the line into evil by joining in and raping the hapless soldier. Much like group horror films where the protagonists undergo a change of heart and turn into villains, Flandres captures this moment with raw savagery and lack of emotion.

Dumont also employs the descent into chaos tactic with Barbe in the France scenes where she undergoes an Exorcist-like transformation into a violent and self-destructive woman who eventually must be put under psychiatric care. The real life cause of her diagnosis: boredom and neglect. Each storyline in the film seems driven by a supernatural possessor, causing the characters to inflict pain upon anyone they encounter, including themselves.

A former philosopher-turned-filmmaker, Dumont’s films are permeated with brutal violence, sometimes unseen, sometimes in-your-face, but it is always stylized in a horror-influenced manner.

3. Kids (1995) – Larry Clark

Sometimes non-horror films can be treated like ghost stories, and Larry Clark’s collaborative effort with Harmony Korine works as both a cautionary tale and a ghost story both at the same time. The film takes place in the mid-1990s and portrays an unmistakable adolescent nihilism representative of that decade.

The spectre haunting the characters throughout the film: The Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV). Almost as if the film infects the viewer with HIV, the dizzying and gritty visual style almost takes the perspective of the virus causing as much discomfort as a scary campfire story with the moral at the end further solidifies the point.

Being a network narrative of characters, Kids does not have a main protagonist or antagonist per se. However, the main plotline (if viewed as a ghost parable), would surround Telly (Leo Fitzpatrick) and Jennie (Chloë Sevigny). Telly is a sixteen-year-old boy who loves to deflower young virgins, Jennie is one of Telly’s conquests and is the only boy she ever slept with.

After accompanying a friend to the clinic to get checked out, Jennie learns that she contracted HIV from her sexual encounter with Telly, and an oblivious Telly is out spreading the disease among young girls. The plotline is shocking enough, but what follows is 24-hour day that quickly dissolves into chaos, building up to a party where decadence and pleasure take the front seat and Telly and Jennie remain out of contact despite Jennie’s attempts to give Telly the bad news.

The film is a bit dated, and a few anachronisms will be caught (it was an age before cellphones after all), but the suspense in wondering where the film will end up going is just as gripping as a campfire story. Korine’s script oozes with teenage lingo while Eric Edwards’ economic hand-held grainy cinematography gets up close and personal with the exchange of bodily fluids and sexual activity. Despite Kids’ big-city backdrop, it is clearly relayed to the audience that this story could happen anywhere.

4. Trainspotting (1996) – Danny Boyle

Moving on from the real life category of non-horror films, the notion of substance abuse is very much a realistic and horrific take on what can be done to the human body, however substance abuse works on the mind much like a psychological or body horror film would depict. Danny Boyle’s film Trainspotting not only works under a horror perspective, but also as dark comedy, much like An American Werewolf in London did.

Taking place in a slummy area of Edinburgh, Scotland, the film tells the story of a group of young heroin addicts and their own personal addictions. Each one has a different approach to drug use. Some are more conservative while others are full-blown addicts. However, it is through Renton (Ewan MacGregor) do we get an in-depth perspective of the horrors of heroin addiction.

Renton’s journey is fraught with horror and comedy alike and Danny Boyle employs the postmodern tactic of rooting his film in classic imagery surrounding film and music. Mindless conversations about Sean Connery prevail, a bar is adorned with images from A Clockwork Orange and Taxi Driver making Boyle’s references to horror cinema not a surprising addition to the film.

Calling this a dark comedy horror may seem like a stretch but it has many aspects of a bizarro-horror film. The film contains gutwrenching scenes reminiscent of exploitation horror films from the 70s and 80s, where the focus on bodily functions is almost comedic, such as Renton’s unfortunate anecdote in “the worst toilet in all of Scotland.”

Boyle also throws in shock by having the audience witness a baby’s death due to neglect from a heroin addicted mother. Renton suffers from an overdose later in the film and is trapped inside himself while Velvet Underground’s “Perfect Day” drones on as he needs to be revived, leading to the film’s most talked-about sequence where Renton must kick the habit cold turkey.

The latter sequence is where many compare Trainspotting to a horror film. Here Renton hallucinates and screams in terror as memories and characters from his junkie life goad him and taunt him, even the dead baby from earlier on makes an Exorcist-like appearance. It is an eye-opening sequence and lends the film more horror chops than most addiction-based plots.

A further examination of the horror potential this film has is in Robert Carlyle’s character Francis Begbie, a homicidal maniac who is only friends with the group out of their sheer terror of him. In the film he beats, stabs, and stomps on people who look at him wrong or disagree with him. This loose cannon of a character keeps the audience on edge and tensed up every time he is onscreen.

Danny Boyle’s postmodern mixture of all these elements does create a layered and unique horror experience, it has a mix of almost every subgenre there is.

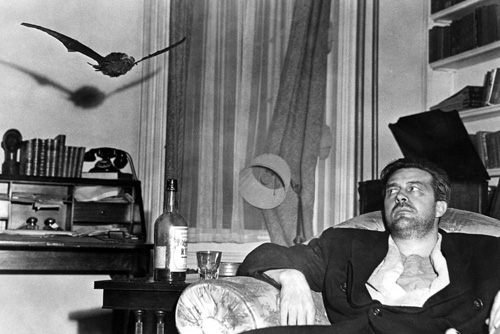

5. The Lost Weekend (1945) – Billy Wilder

The only classic entry on the list is a great progenitor of films like Trainspotting. Billy Wilder’s Oscar-winning film about alcoholism is pretty tame by today’s standards, but stylistically it is one of the outspoken classics of its genre. A mixture of film noir and melodrama by one of cinema’s greatest directors, the film is about Don Birnam (Ray Milland), a struggling writer suffering from alcoholism.

As he tries to write a book about alcohol addiction, he boozes and binges and ignores help from his concerned brother and his girlfriend who want to see him kick the habit and flourish as an excellent novelist. It is a slow and torturous experience to watch Birnam plummet into the depths of drunkenness and Billy Wilder captures it with his trademark dark style.

Borrowing more from the classic side of horror, particularly the work of the Germans (Wilder was Austro-Hungarian after all), The Lost Weekend has the workings of an old creature horror or an Expressionist film like Murnau’s Nosferatu. It all comes down to the clash between light and dark, the first and foremost facet of horror cinema.

Much like Nosferatu’s Hutter with Count Orlock, Don Birnam becomes enslaved by the bottles of rye he keeps hidden in his apartment and he is drawn to the bars as if under hypnosis by a vampire himself. He makes excuses and steals money, he tries to pawn off his valuables to get a sip.

During the day he is sly and helpless, but come nightfall he becomes obsessive and vampiric. The site of a single drop of rye make his eyes like those of sharks at the scent of blood, and it all culminates into a psychological episode like something out of “The Twilight Zone.”

This contrast between light and dark keeps this film on the borders of horror and melodrama. Once again it is more of a real life situation, but the eventual detour into Don’s mind near the end of the film gives the already sharp film even more of an edge.

6. Requiem for a Dream (2000) – Darren Aronofsky

After his quasi-horror debut π (1998), Darren Aronofsky released his second effort, which is the soul-crushing masterpiece that is Requiem for a Dream, taking the form of a funerary music piece, the film is pure horror, right down to Clint Mansell’s influential and sombre film score used throughout the movie.

Excellently performed, and visually heartwrenching, Requiem for a Dream journeys into very personal and dark territory, going so far as to be called a horror film in its own right due to how shocking it is. Although there are many sites and books that cite this, here is a good one.

Based on Hubert Selby’s 1978 novel of the same name, the story follows a small group of characters who each eat the rotten fruits of addiction. Not being based on addiction to a single subtance, the film explores various forms of addictive behavior, whether it be food, dieting, television, sex, and drugs, there is a bit of everything covered in the film.

Each character has a unique voice and endures at least one soul-flattening moment that leaves the viewer sympathizing with them as if they were the victims of an evil force or spectre. Much like Kids, the spirit of the unseen lingers in every scene, only in this case it is sometimes manifested physically. At one point a happy-go-lucky binge turns into a supernatural attack made real by the lucid state of the character, and the results are heartbreaking.

Although the whole cast turns out amazing career-defining performances (especially silly comedian Marlon Wayans who goes against type), the most memorable moments of the film revolve around veteran actress and Exorcist-mom Ellen Burstyn’s character Sara Goldfarb. Her journey is so tragic in the sense that she is thrown into a nightmare by no real fault of her own. She is attacked by old age, media conglomerates, and her own body.

After receiving a call telling her that she will appear on television, her solitary life finds new meaning and she longs to fit into a red dress she once wore years ago. Needing to go on a diet to lose weight, she is prescribed that will allow her to drop the pounds without needing to cut back on the junk food. Throughout her storyline, her physical and mental deterioration become tragic and finally come to a head when she is basically attacked by everything she is working at to achieve.

The rest of the cast do have their own pitfalls too, with consequences ranging from the loss of limbs, to confinement in an unfamiliar setting to group sex and it is all captured under a distorted lens and Clint Mansell’s bleak music. The film also plays to a Japanese anime-horror tune as is clearly evoked in some of the more surreal moments in the film, but one could go on and on about how horrifying this film is.