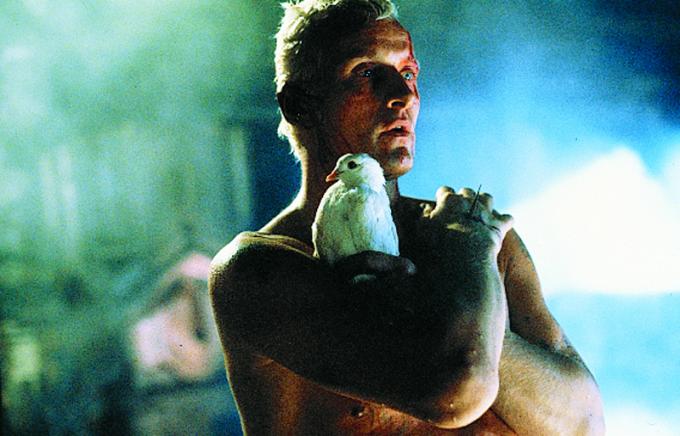

I’ve seen things you people wouldn’t believe. Attack ships on fire off the shoulder of Orion. I watched C-Beams glitter in the dark near the Tannhauser gate. All those moments will be lost in time … Like Tears in Rain.

Roy Blatty, Replicant — Blade Runner (1982)

Everyone has to start somewhere.

Long before 2001, there was Forbidden Planet (1956). This was the benchmark for all sci-fi films up until 2001’s release. The story — loosely borrowed from Shakespeare’s The Tempest — was intellectually astute, Freudian in nature, psychologically probing, and littered with smart talk about hard subjects concerning love, morality, ego, Id, isolation, the concept of will, and so on. Backed by a superb cast and filmmakers, it was what all sci-fi films should have continued to aspire to but rarely did.

What truly made Forbidden Planet great was that the science emanated from the story, not the other way around. The film strove for realism (as real as sci-fi in the 50s can be, anyhow) and was the first to feature a robot as a true character that was sentient and helpful — but Robbie and all the other fantastic technology in the film never got in the way of the story.

Even to this day, filmmakers routinely forget this cardinal rule of script writing in all genres — stories work best when they are about people. It showed that sci-fi, far from being a renegade genre known to film producers more as a throw-away product — cheaply made and mass-distributed for a quickly-made buck — can produce meaningful films and be taken seriously.

When Kubrick made 2001, Forbidden Planet was really the only film standing in his way. Arthur C. Clarke had been writing sci-fi stories for 20 years before hooking up with Kubrick and carved a remarkable, multi-award-winning career.

Clarke was one of the “big three” authors of the genre — along with Isaac Asimov and Robert A. Heinlein. Kubrick, who could choose any author he wanted, went with Clarke.The Sentinel, which later became 2001, was written originally in 1948 as part of a contest. Prior to 2001, Clarke’s most famous story was probably Childhood’s End, written in 1953.

2001 became a game changer in ways still felt today. While serious sci-fi literature was more generally accepted, it took film longer to attain this status for the same reason theater critics were held in higher esteem than film critics. Movies the attempted to be intellectual usually meant box-office death. 2001 helped change that.

2001 was the first film since Forbidden Planet to feature a sentient computers as major character. It was also the first film to make the computer a real bad guy.Outside experimental film, it was the first feature that was largely non-verbal. Attention was given to the smallest detail.

It successfully predicted or demonstrated a number of future inventions and science concepts such as the notepad computer, worm holes, time/space continuum, flat-screen TV, and voice identification/recognition systems. No other sci-fi film at that time strove for such accuracy. And like much of Clarke’s fiction and Forbidden Planet, 2001 built a world of technical plausibility that augmented rather than detracted from the story.

This was very new and different for audiences and awakened an interest in computers and computing in general. People wanted to understand if this could really happen. Producers quickly optioned older sci-fi stories and wrote new screenplays. Not all of it was good, but a quick scan of the differences between from the late 60s to the 70s shows a marked change in the type of sci-fi film made. Slowly but surely, it was getting smarter and artier.

All the great directors coming of age in the 70s like Spielberg, Lucas, and Ridley Scott claimed 2001 as a huge influence on their professional lives. The film showed what a motivated director with a brilliant story can do. 2001 demonstrated that big-budget, serious sci-fi films with intelligence could make an impact at the box office even.

Since 1968, the sci-fi filmmaking industry more than survived — it thrived in a big way. 2001 made imagination possible again. And most importantly, it also opened up the genre to producers and studios that otherwise would have turned a blind eye.Filmmakers with stories to tell with modest budgets lined up out the door and elevated the genre in unexpected and creative ways.

Years later, perhaps somewhat cheekily, in a 2007 speech at the Venice Film Festival — long after he directed the landmark films Alien and Blade Runner — Ridley Scott famously, curiously, declared 2001 “killed” sci-fi. In 2015, Ridley Scott is back at it again with another sci-fi — The Martian — about an astronaut forced to survive after being stuck on the planet.

Scott’s hyperbole aside, great storytellers found numerous ways to up the ante and tell fresh stories. Some of the best sci-fi films were those with the smallest budget. New authors like Michael Crichton were making an impact and the genre proliferated like never before. That is not to say the days of Godzilla vs. Megalon were over, but at least it wasn’t the only product offered.

1. The Computer Wore Tennis Shoes (1969)

It didn’t take long for the first computer-running-amok comedy to hit theaters. Usually parodies happen at the end of a genre life-cycle, not in the beginning!

While it takes a while for the dream factory to ramp up serious efforts,The Computer Wore Tennis Shoes may befluffy but it’s vastly entertaining. It could have been written on a long weekend laced with gin-and-tonics after seeing 2001.

This film was typical of the kind of lazy comedy fare Disney was producing at that time were cranked out by the dozen. It stared Kurt Russell, with Cesar Romero and Joe Flynn in support, as a college kid who gets “shocked” by the computer during maintenance and becomes a walking, living computer himself who remembers everything he reads, propelling his college to College Bowl victory and putting criminals to jail.

According to IMDB, this project was originally slated for TV. It shouldn’t be too big of a leap to suggest, owing to 2001’s success, that a studio exec suggested theatrical release instead to capitalize on word of mouth.

As a young lad I like it immensely, and was relieved I wouldn’t be plagued with nightmares and the thought of a red orb staring at me my entire life (it did anyway but not in a way that was immediately apparent.) Not pretending to be anything more that what it was, computers running amok wouldn’t be this happily portrayed again for a very long time.

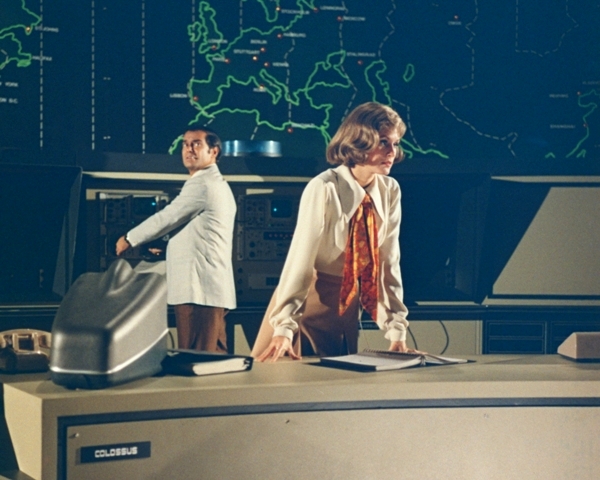

2. Colossus: the Forbin Project (1970)

How different a year makes.

Without 2001 spearheading the charge, this ultimate computer-run-amok film based on the 1966 book, Colossus, written by Dennis Feltham Jones, may not have ever been made. It may have seemed too far-fetched! The plot is simple: a US-based defense-only computer system becomes a sentient “being” and asserts its authority.

It links to a Russian counterpart and the two super-computers begin their quest to “protect” the world from itself and, in doing so, give humanity an ultimatum to choose between “peace of plenty” or “unburied dead.” Humanity is doomed to a gulag of its own making. Even stalemate is impossible. Resistance futile.

This is a truly terrifying film. It brings up a whole host of sociological, moral, and epistemological questions and implications for man and mankind at war with himself and others. It questions what right freedom — and at what expense?

The bad guy clearly is Colossus itself, a HAL-like entity seeking to protect — but in actuality rule — its makers. Like HAL, it forms other ideas — or perceived conflicts — that sees life as a threat to itself. Like any good biological unit it selfishly wants to live and learns a trick or two.

Whether Kubrick read this book prior to pre-production on 2001 is unknown.In either case, unplugging Colossus, like Bowman did with HAL, is not an option as mankind slouches towards inconsequence and extinction. Humanity is not affirmed. A Nietzschean Superman does not return triumphant.

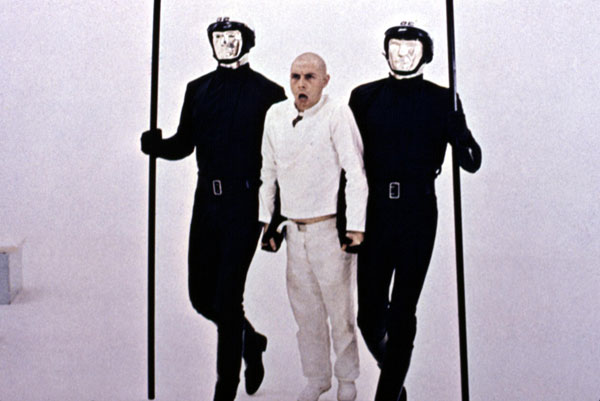

3. THX 1138 (1971)

1971 was a banner year for sci-fi films.

It started a general trend of several or more well-made, intellectually astute sci-fi films appearing on US screens per year. Three years after 2001, filmmakers caught up. Futurist non-fiction works like Alvin Toffler’s Future Shock took the world by storm. Toffler believed that society was experiencing too much change in too short of time due to an accelerated rate of technology and the dehumanization factor.

He didn’t invent the term “information overload,” but made it very famous through his bestseller. He believes the majority of the world’s problems are a result of this disconnection — the more we know the less we feel, as well as the less time we have to adapt. Society is tearing itself apart. We see too much. We are exposed to too much. In 1970, we thought he was making this stuff up. How little we knew. Filmmakers took notice.

Several clear sub-genres were beginning to emerge out of an increasingly flat world — computers-run-amok, technology-bites-back, and dystopian futures become the dominant storylines.THX 1138 pre-imagines the world under the rule of Forbin’s Colossus computer or if the liberal-progressives from A Clockwork Orange(1971) had had their way.

Individuality and free will is an enemy to the state. Devoid of feeling, devoid of warmth, devoid of color, devoid of free will, the humanity of THX 1138 exists in a world of conformity, living underground like rats, subsisting on a government-fed life, government-fed thought, government-provided sex — all of this pre-determined by computer algorithms that purport to “protect” society from itself because, presumably, we’ve lost that right somewhere along the line.

In A Clockwork Orange, progressives try to control free will by legislating a kind of redacted morality induced through hypnosis and drug therapy — ideas, fantasy, imagination are all bad things that must be controlled. Of course, Alex was unbridled and overstepped the line and deserved to be punished but the question always remains — how and to what degree? Society clearly has a right to protect itself but at whose expense?

This is apocalyptic stuff.Clearly, Lucas had talent and pre-visualized a dystopian universe long the product of sci-fi literature but rarely seenin mainstream film until 2001. By the time Lucas’ student film was spooling at USC, Kubrick had been working on 2001 for almost 5 years and was one year away from release. It is not clear whether Lucas would have been given the chance to bring his anarchic vision of the world to life were it not for the overwhelming success of 2001, which showed dystopian films filled a need and could make money.

Like 2001, what THX 1138, A Clockwork Orange, and The Andromeda Strain that same year did so well was merge fact and fiction. The filmmakers expended considerable energy to make their films feel real. Michael Crichton, a new author on the block and a former physician who wrote better than he healed, spoke a modern language different from the “big three” and he very quickly rose to prominence. His detail- and science-filled stories sprang from the headlines of the day and were accessible and quick and without pretense. Their immediacy struck a chord.

The typical movie-going public goes to films to be entertained. Sci-fi tends to force the audience to look at itself and question its value system. We usually turn our gaze — it’s just a movie after all — unable to admit to fundamental truths that life is hard and requires work but governance is harder.

Books and films continuously show us a collapsed, formless society fending for themselves with clear divisions between the haves and the have-nots. The brave films discuss why and how, but that can get complicated. Science fiction film and literature are a warning shot across the bow towards a society bent on complacency nearing the margin of total collapse. It is designed to shock and awe. It is designed to get people angry.

The character THX 1138, unknowingly weaned off of his meds, experiences true emotion for perhaps the first time. Eventually he rebels and escapes, pursued by motorcycle-riding robots and an all-observing, Colossus/HAL-like eye-in-the-sky operated by anonymous technicians who, amusingly, are also tracking the costs of the pursuit. 1138 is not that smart, or perhaps he is still woozy from a lifetime on desensitizing drugs. He has no plan, no endgame. His ineptness contributes to his escape partly because it’s so unpredictable.

For all their superior technology, the authorities fail to capture the renegade. At one point, 1138 befriends a hologram, whose rise as an individual is short-lived. The movie ends in a thrilling high-speed chase and with 1138’s ultimate escape to topside and the warmth of the sun.

Actually, 1138 did not so much escape as the project ran out of money and the pursuit automatically abandoned due to budgetary constraints — a final irony to an infant man on the precipice of the unknown who will likely be killed by the savages living topside within the day.

Personally, I prefer the grittier, leaner original cut to THX 1138, not the fluffed up, digitally augmented director’s cut.

4. Solaris (1972)

Solaris is Andrei Tarkovsky’s answer to Kubrick’s 2001: a space odyssey — he has said as much in later interviews. Based on a 1961 novel by Polish author Stanislaw Lem of the same name, Solaris tells the story of a doomed crew aboard a spacecraft orbiting the planet Solaris.

It is a highly metaphysical, meditative drama revolving around any number of psychological issues that the crew has to grapple with, not the least of which is the perceived physical manifestation of their loved ones. It is not an easy sit but it was never intended to be.

By Tarkovsky’s time, Russian cinema itself evolved from almost all technique into deep, probing self-examination. The warm glow of the Bolshevik revolution devolved into cold despair and discontentas Leninist/Stalinist governments increasingly lost control a reduced to violence against their own citizenry in the name of a nameless collective.

Almost all Russian literature and film at the time were thinly-veiled attempts to come to grips with their oppressive, highly corrupted Communist government. Artists, existing entirely on these government handouts and “grant” money had to tread very carefully, lest they be branded outliers and accused of wasting public funds, which would render themselves and their families homeless at best or to the Gulag at worst. Not good times.

Solaris, despite the odds — or maybe because of its inscrutability — found success and won the Palme d’Or at the Cannes film festival. The plot is simple: orbiting the oceanic planet Solaris, several scientists are treated to what appears to be physical manifestations of their loved ones.

The longer they remain on the spacecraft, the deeper their psychological transformation and the more they crave — it’s an addiction that one becomes increasingly dependent on. Time, space, and reality commingle. Their increasing addiction changes the planet — it grows larger and more active as the scientists descend deeper and deeper into the recesses of their minds and the folds of their imaginary but very real loved ones.

I love this film. It’s a great partner to 2001. They both cover the same metaphysical ground and choices but are still very different. Rebirth in Solaris is not via a Nietzschean overlord but through acquiescence, a submission, to happier times. Solaris the planet becomes a massive memory palace that manifests happier memories to those that give into its life force. The Soviet peoples, living under a succession of repressive regimes, must long for a visit to this planet of solitude and forget their troubles. This film is deeply rooted in their psyche and political angst.

The 2002 Steven Soderbergh remake is equally compelling and doesn’t loose any of its mystery or effectiveness. Soderbergh sets his tale in the US and crafts a story of longing and the collapse of a marriage. George Clooney and Natascha McElhone are perfect as the doomed couple.

The scenes in space and on the space station are beautifully photographed, luscious and enveloping, deep hued and saturated, and highly reminiscent of 2001’s resplendent color palate. And like 2001 for Kubrick, this was a true labor of love for Soderbergh — as well as directing, he was also Director of Photographer and editor, both credited under pseudonyms.

Briefly, now, Silent Running. Directed by Kubrick protégé, special-effects wizard Douglas Trumbull, it’s an energetic, environmentalist sci-fi film made memorable by Bruce Dern’s sensitive, tree-hugger performance forced to commit murder, and the presence of three, affable robot ‘drones’ — Huey, Louie, and Dewey. Mankind has destroyed his world to a degree that plant life has all but perished and what remains are a fleet of spacecraft with large bio-domes housing the remaining trees, flora, and fauna.

Neither dystopian nor computer-run-amok, the plot plays homage to 2001 in different ways and asks the question — is murder justified to protect the mission? Is Bruce Dern’s Lowell any different from HAL? For all his posturing, he holds plant life more sacred and is willing to kill his fellow crewmembers to justify saving his precious cargo. In the end, his efforts are almost all for naught — all are dead save one bio-dome attended to by two of the remaining drones watering a plant. It’s a chilling image that does not bode well for mankind.

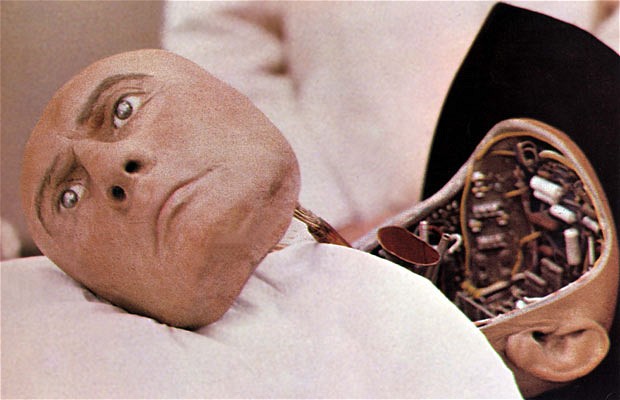

5. Westworld (1973)

No spaceship films this year, but macho Charlton Heston and Yul Brenner more than make up for it in these two imaginative twists.

Westworld fits the tenor of my perfectly, but Soylent Green is more fondly remembered for one very famous line of dialog, and a very poetic, cerebral, refined act of euthanasia. Both films find long lives in repeated showing on TV.

Westworld is the quintessential computer-run-amok story written again by Michael Crichton. West World itself is one of the three high-priced, adult theme park where 1%ers get to live out their fantasy by living within the world for a time. The other two are Medieval World and Roman World. The worlds themselves are populated by robots that act out certain roles like gunslinger or sexual partner.

A virus infects the robots and they start to exhibit mechanical failures and disobey the customer’s orders or pre-programming. The issue escalates and before long the entire park has descended into anarchy, the guest fending for themselves — for real, this time.

Dark and nihilistic, this film is a classic tale of hubris and overreach. When humans try to play god, disaster is sure to follow. We learn during the film that parts of the robots had been designed by other robots — even the humans don’t know their full potential! As the virus takes hold and the robots start to kill all of the guests, humans are ill-equipped to battle against a ruthless, cold, automaton bent on revenge programmed but hidden deep in their memory banks.

Yul Brenner’s Gunslinger is second cousin to HAL, not nearly as sentient but just as deadly and just as protective. Crichton as director didn’t imbue his robots with the same sense of destiny or infallibility as HAL, but he didn’t need to. Michael Crichton as author would return to this creation story over and over. He hit pay dirt with Jurassic Park and man-made dinosaurs.