The invention of the camera dramatically altered human perceptions and began a debate about, “the truth?” All art, from the dawn of man onward, is artificial and inherently subjective to some degree, but the technology invented in the 1800s was truly new and different in a meaningful way.

Beginning with still photography, then audio recording, and finally moving pictures, all recording devices capture an impression of the world that is mechanical and inherently objective to some degree. Media experts often casually dismiss the assertion that, “the camera doesn’t lie,” because any change in lighting, or slightly different cropping of the frame, etc. may dramatically alter the viewer’s understanding of what is being shown.

In a way this is a valid point but it is also a bit of intellectual trickery, because the camera has no intentions and therefore it is incapable of lying. It can only perform a mechanical function and it will do it the same way, under the same conditions, consistently.

The Lumière brothers were the first to publically exhibit films they had shot and from the outset their work raises questions about the “truth” of what we are seeing. One of their earliest shorts, Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory (1895) appears to be a straightforward record of their employees leaving work and walking past the camera; a “true” moment preserved for future generations.

If you look deeper into the Lumière archive, however, you will find that they shot multiple takes of this, “leaving,” looking for the timing and overall composition they liked best. It is unclear how much of the film was staged but it is commonly seen in hindsight as a, “documentary,” nonetheless, because it documents reality more than it manufactures a fiction.

Documentary filmmaking was relegated to a small niche market and its practitioners were generally little known until the invention of videotape and cheaper, more portable film equipment in the late 1950s. The 60s became identified with a new, semi-journalistic style of filmmaking, that is part historical document and part high art. The umbrella label commonly applied to this era is, “cinéma vérité” (cinema truth), despite the fact that the films it lumps together were not made with a coherent understanding of what “truth” they were aiming to show the audience.

French filmmaker and anthropologist, Jean Rouch coined the term, “cinéma vérité,” after the Soviet newsreel series, Kino-Pravda (Film-Truth). Rouch was fond of saying, “Glory to he who brings dispute,” and his work very intentionally mixed fact and fiction, documenting spontaneous reality and provoking improvisational scenes. His most interesting film is Chronique d’un été (Chronicle of a Summer), which begins with a discussion about how true the camera can capture reality, or how true people can act in front of a camera, then it moves into a serious of discussions with non-actors on a number of topics.

At the end these same people watch the footage constructed from their conversations and then discuss the degree to which the film is true. It’s a fascinating, somewhat surreal perspective on reality, or the reality of filmmaking, which argues for a new “truth” being created by cinema, more than cinema capturing a preexisting “truth” in the world.

For some Rouch’s conception defines the “real” cinéma vérité, which should be experimental, playful, and push the boundaries of film’s unreal nature. The term, “cinéma vérité,” has also been extended by some to the anti-cinema, cinema of Andy Warhol, who made movies like Sleep (1963) and Empire (1964) that challenge the conventions of filmmaking and make viewers very aware of the fact that they are sitting in front of a screen.

In the former we watch Warhol’s friend and occasional lover, John Giorno, sleep for more than five hours. In the later we watch the Empire State Building, as seen from the forty-first floor of the Time-Life Building, for more than eight hours. The “truth” here is that movies are inherently boring.

The most common view of what cinéma vérité means, however, comes from its application to the, “direct cinema,” movement popular in Canada and the United State, which takes a, “fly on the wall,” unobtrusive, detached perspective. The goal here is to record the real world as it might be without a camera. This is a controversial proposition, since most people are very aware of any cameras around them and tend to act up or downplay their normal behavior when they are being recorded.

To use a great fiction film example, there is a scene in Apocalypse Now (1979) where the director of the movie, Francis Ford Coppola, appears in the film playing a documentarian or journalist, shooting footage of U.S. soldiers in Vietnam. As we watch each trouper pass in front of the on screen cameraman they can’t help but look at the device in their face while Coppola yells at them: “Don’t look at the camera! Just keep moving!”

It is a clever depiction of the difficulties involved with getting people to, “act normal.” If you need to tell them to, “act,” then it’s not normal. Nevertheless, there are documentarians who have taken this approach, and successfully navigate the pitfalls of film’s limitations to show us something genuine through the medium.

What these journalist-historian-artists create is not just a profound truism about life, which many fiction films accomplish, or a uniquely cinematic truth, as Rouch and Warhol did, but a profound experience that resonates on another level. You feel as if you have travelled back in time and been present with the people on screen, at the moments you are privileged to witness, because somebody really was there with them, recording it.

You leave these films feeling that you know the subjects in a way that books and fiction films cannot match. There are many great works that might appear under this definition of, “cinema truth,” but the following list are the essentials that anyone interested in the genera must see.

1. Nanook of the North (1922)

Robert J. Flaherty lived with Inuit Artic natives for many years prior to taking a camera into their community. His first attempted version of the film, made in the nineteen teens, burned up in a fire, but this proved serendipitous, because it forced him to rethink the project.

Flaherty felt his film had been too much of a, “travelogue,” similar to most of the documentary work done since the Lumière brothers. For his second version he chose to focus on a single man, Nanook, and his family. It made this into a story with characters the audience cared about and rooted for. The end result is commonly considered the first feature, “documentary.”

John Grierson, a Scotsman who would go on to become the, “father of documentary,” film in Canada and the U.K., coined the term, “documentary,” in a review of Flaherty’s second film, Moana (1926). For that production Flaherty lived on a Samoan island in the South Pacific to create another portrait of native live. Critics of Nanook, Moana, and Flaherty’s work in general, point to his staging of events as a huge mark against him and the truthfulness of his films.

Some of Flaherty’s staging was out of absolute necessity, like building half an igloo and using it as a set to show how the Eskimo slept. Given the large size of the camera he had to work with and its inability to operate in low light conditions, this simulated shot was the only thing he could get, “inside” an igloo.

Some of his other choices are more questionable, like getting Nanook and his friends to hunt with spears, the way their forefathers had, rather than rifles, and calling his protagonist, “Nanook,” rather than using his real name, Allakariallak. In defense of Flaherty it is necessary to step back and think long and hard about what he accomplished and how he had no guidebook to tell him what would later be considered proper documentary behavior.

As film critic Roger Ebert once said, “[Nanook is] one of the most vital and unforgettable human beings ever recorded on film [and this documentary] has an authenticity that prevails over any complaints that some of the sequences were staged. If you stage a walrus hunt, it still involves hunting a walrus, and the walrus hasn’t seen the script.

What shines through is the humanity and optimism of the Inuit.” The film also set the standard for how many great documentaries would be funded, by nontraditional film investors, rather than big Hollywood Studios. In the case of Nanook, the funding came from a fur company.

2. Primary (1960)

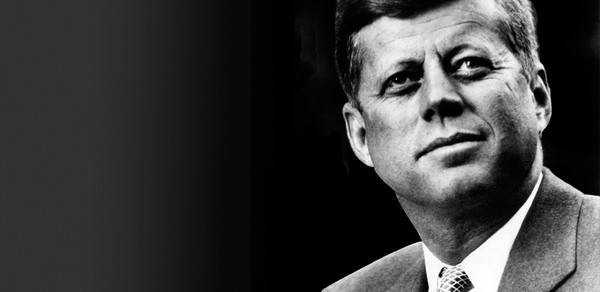

Made by Robert Drew, Richard Leacock, Albert Maysles, and D. A. Pennebaker, this groundbreaking production follows Senators John F. Kennedy and Hubert Humphrey through a Primary Election battle in the State of Wisconsin. Leacock started out working for Flaherty as a young man in the 1930s and all of these filmmakers continued on to notable careers. Advances in technology allowed them to get up close and personal with the candidates and the crowds.

Like all Kennedy footage, Primary has taken on a special significance ever since the young President was murdered before completing his first term, but this footage in particular speaks to the rock star magnetism that put him in the White House. Humphrey, who would go on to be President Johnson’s Vice President, is largely forgotten these days, but Primary also serves to remind people about this great and kind man. He was no match for the celebrity of Kennedy but he was an equal in intellect and a pioneer in moving the Democratic Party from Segregation to Civil Rights.

The narration at the beginning of Primary says that this could be any election, at any time, and lists several, older politicians before 1960, but in many ways the film could still be about the primary fights of today. It is a wonderful record of what has and has not changed about electioneering.

3. Crisis: Behind a Presidential Commitment (1963)

Even better than Primary is Robert Drew’s film inside the Kennedy Administration during the June 1963 standoff over school integration in Alabama. The state’s infamous Governor Wallace vowed to, “Stand in the Schoolhouse Door,” at the University of Alabama and not allow two, “Negros” to enroll. He was openly defying a court order with the old refrain of, “States Rights” as his defense.

We have a place in the crowd as Wallace faces off with the Assistance Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach and a front row seat back in Washington with Attorney General Robert Kennedy, trying his best to resolve the conflict without losing his brother the Southern Democratic support he would need for reelection.

One of the great moments is a very simple one, as Robert Kennedy talks into a primitive speaker phone and can’t get any clear word about what is going out. You understand in moments like this how all power has its limits and even great power can be severely limited by the simplest obstacles.

The best part of the film is the ending, when we watch part of the President’s landmark Civil Right address, hastily constructed in the hours following the resolution of the crisis and delivered to a national TV audience. The editing is very clever, cutting to Wallace looking up suddenly as President Kennedy asks what white person would want their skin turned black and suffer the mistreatment that, “Negro” Americans live with?

Obviously, this cut, and others, is not completely honest to the exact sequence of events, but it truly represents the conflict and the time. The President was speaking to men like Wallace and may have even had some affect on them. Many years later, after surviving an assassination attempt, Wallace would apologize to the African American Community for the man he once was.

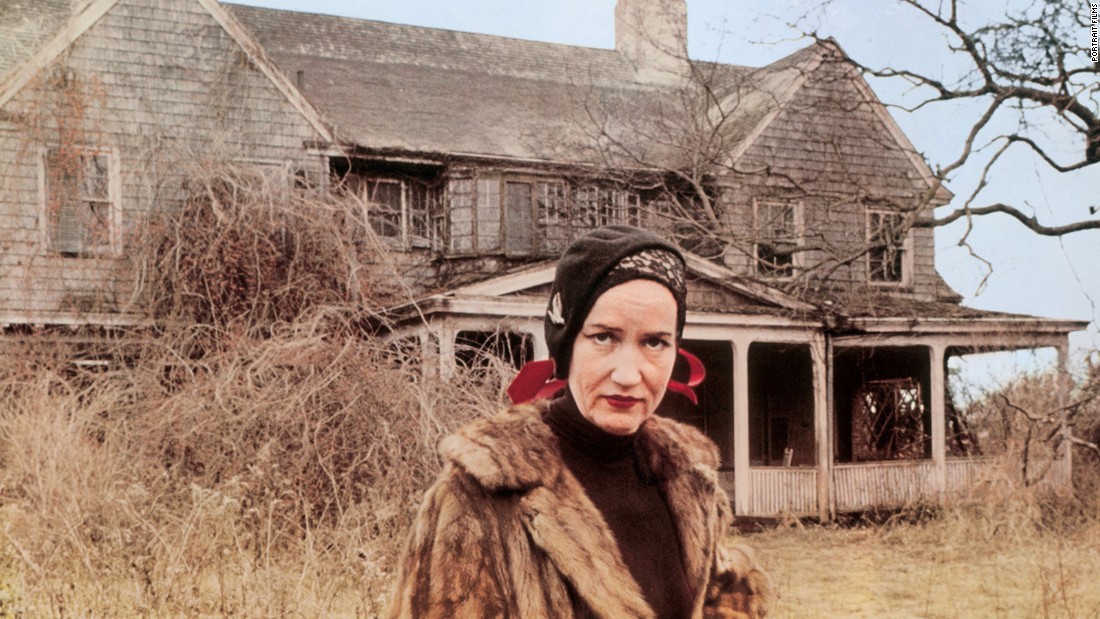

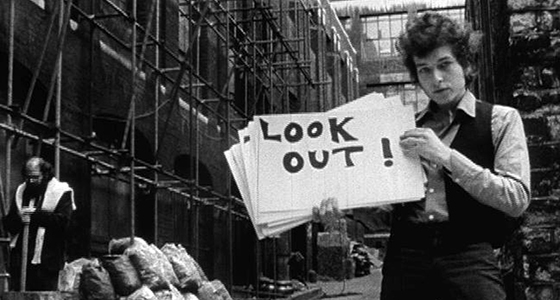

4. Don’t Look Back (1967)

D.A. Pennebaker headed up this production, which followed Bob Dylan on his 1965 tour, mostly in the U.K. Dylan is known for being cagy figure, who often seemed to be performing, no matter if there were cameras around or not, so it is hard to judge the reality of the film, but it feels true.

The one clearly staged scene is the legendary opening, where Dylan flips over cue cards somewhat in time to the music of his song, “Subterranean Homesick Blues.” This sequence would be used as a trailer for the film and it is now seen as a precursor to the music video revolution that would come more than a decade later.

Two decades later INXS would homage this in their music video for the song, “Mediate,” which still felt fresh at the time and still feels fresh today. Other noteworthy figures make appearances in Dont Look Back, include Joan Baez, whose romantic relationship with Dylan was clearly coming to an end at this point and cult Beat Poet Allen Ginsberg. This is a record of the hip 60s that people born too late feel they missed out on.