The nature versus nurture debate has troubled philosophers across the world since the days of Aristotle. The world of cinema is the perfect medium to settle the score; cinema holds up a mirror to society; the camera won’t hide a terrible parent from the truth. So here is conclusive evidence to settle this age old conundrum.

Most parents in this list are from the world of horror; other, comedic movies present acidic satire on the perils of being a child when your mommy or daddy has a few screws loose; one movie features parents who are terrible because…well, they’re just not all that smart. Both genetically and in the way you’re (horribly) raised, if you’re the unfortunate child of any of these mamas and papas, the debate has been settled: you’re simply cursed! Please note this list is ranked in no particular order.

1. Jerry (The Stepfather, 1987)

The opening sequence in this suspenseful thriller shows the butchered corpses of a mother and her young daughter; it’s no surprise that homicidal stepfather, Jerry (Terry O’Quinn) is up near the pointy end (sorry) of this list. In a decade flooded with commercially successful horror franchises featuring crazy men hacking up innocent youths (A Nightmare on Elm Street, Halloween, Friday the 13th) Stepfather carved (sorry again) its own niche and became a sleeper hit.

O’Quinn’s chilling performance is the major reason the film hits the mark. He very effectively underplays the part of a mild-mannered, congenial real estate agent, who preys on widows and inevitably kills the entire family. Jerry’s charm and well-balanced dependability don’t fool 17 year old Stephanie (Jill Shoelen); there’s something not right about her mother’s new beau.

The cold-eyed man we saw washing his blood-stained hands in the slain family’s basin in the opening sequence is merely one imagined “disappointment” away from snapping again. Stephanie’s also had some serious troubles at school. With the support of a psychiatrist, she is mourning her father’s death and — along with her best friend, Susan — finally has someone in which to confide her grave fears. But will the truth about Jerry be revealed before he claims his next victims?

While The Stepfather is clearly a mainstream genre film, there’s a reality to the notion of a stepfather – essentially a stranger — imbedding himself in family that evokes unease, if not out-and-out fear. While most don’t turn out to be serial killers, the horror of this situation for a vulnerable young woman dealing with the death of her father is very relatable.

O’Quinn’s latent rage — quiet and cunningly amiable to the unsuspecting – is all the more frightening for its believability. But when Jerry decides to fully unleash, he is truly the Stepdaddy of terror!

2. Jack Torrance (The Shining, 1980)

Nicholson’s ultra-psychotic performance is one of the most fearsome displays of unhinged parenting ever committed to film. Just check out Nicholson’s extraordinary “ axe murder warm up” on YouTube if you need further proof.

All hell breaks loose for Torrance’s wife (Shelly Duvall) and son, Danny, soon after Jack – a writer – accepts a winter caretaker position at the Outlook Hotel to peacefully work on his manuscript. Young Danny’s telepathic ability to “shine” inflicts upon him nightmarish visions of evil forces that have possessed his father.

Some critics (and Stephen King) denounced Kubrick’s vision of King’s novel; citing Jack Torrance’s too swift descent into madness. The film didn’t develop Torrance’s malevolence in a controlled “slow burn” manner. But “slow burn” was never Kubrick or Nicholson’s intent. They set out to create a cinematic villain — inspired by some of Kubrick’s favourite bad guys in movie history, chiefly James Cagney — that would send shockwaves through the conservative households of America.

Thanks to Jack Torrance in The Shining we’ll forever cast one eye over our fathers; just in case they start obsessively tapping on their typewriters or decide to redecorate the bathroom with an axe.

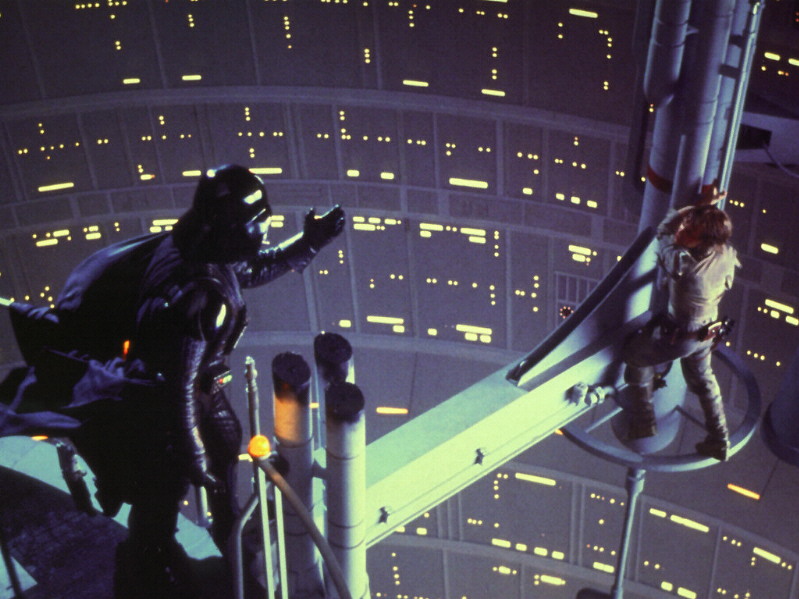

3. Darth Vader (Stars Wars, 1977 – 83)

Over this phenomenal, ground-breaking trilogy, Darth Vader became synonymous with Machiavellian and controlling parents. His final death scene in Return of the Jedi (1983) was intended to make us sympathise with the Sith Leader of the Dark Side of the Force; but the damage had already been done.

What father would plot to firstly kill his son’s mentor (Obi-Wan Kenobi, in Star Wars: A New Hope, 1973); build a death star to destroy all forces of good in the galaxy; then – as icing on the evil cake — plan on a deadly collision course with his son?

The ultimate light saber battle between Darth Vader and Luke Skywalker in the darkest film in the franchise, The Empire Strikes Back (1980) ends with Vader punishing Skywalker for refusing to join the dark side; chopping off Luke’s hand and watching him plunge into an abyss. Father of the year, indeed.

Director George Lucas’ abominable prequels laboured over a hackneyed back-story that justified Vader’s transformation from Jedi, to leader of the Dark Side of the Force, because of a lost love. Die- hard fans never bought this weak explanation. Darth Vader will fondly and forevermore be thought of as the paterfamilias of evil throughout a galaxy far, far away.

4. Mom and Pop (Bad Boy Bubby, 1993)

Billed as an outrageous black comedy, Australian independent director, Rolf De Heer’s film is a horror show; a grotesque display of degradation and abhorrent parenting.

At thirty-five, Bubby (an extraordinary, AFI winning performance from Nicholas Hope) has endured the worst kinds of mental and physical abuse. Kept locked in a dark, wet, windowless basement by his foul Mam, (who warns him of the “poison” infecting the outside world) Bubby sees life differently, like a child. He keeps a pet cat locked to a chain by the neck, until the inevitable happens; then he simply wraps the cat in cling film like a hideous ornament; never emotionally registering the cat’s demise.

Concepts of morality, life and death are completely warped in Bubby’s mind, so that when he sees a chance to escape his abusive mother and pop — a lecherous priest who calls Bubby “retard” and yells obscenities at him — Bubby uses that same roll of cling film to kill his parents and escape into the big, bad world, where he is ironically accepted by a travelling blue-grass band.

Incest, deprivation of liberty, frequent beatings and mentally and emotionally crippling insults are just some of the parenting tools inflicted by Mom and Pop in this cult Aussie film. It’s a jet black, brutal and warped study of how devastating nature and nurture can be when you’re unlucky to end up with parents like these.

5. Mr. and Mrs. Wormwood (Matilda, 1996)

Danny DeVito must have taken perverse delight in gifting him and his wife, Rhea Perlman, the most despicable roles in his directorial adaptation of Roald Dahl’s children’s classic novel, Matilda. As the miserable, conniving, selfish parents of child genius, Matilda (Mara Wilson), DeVito and Perlman have a field day being horrible.

DeVito’s shyster used car salesman — aptly named Mr Wormwood — is a moustachioed, BS spraying terrier; brazen in ripping off his customers, and disgusted when his daughter Matilda calls him out on his deceitful deals.

Matilda’s exceptional intellect and voracious appetite for reading is a danger to the shrill and fluffy haired, Mrs. Wormwood; the child must know her place. But, seen through Dahl’s delightful story, it’s clear that you can’t keep a good young lady down. Discovering untapped telekinetic powers, Matlida uses her smarts to teach her parents (and nasty school principal Trunchbull) a few lessons.

Matilda wisely retains Dahl’s mature tone; never condescending to children or being too moralising. The darker edge makes Mr. and Mrs. Wormwood’s loathing for creativity, decency and basic duty of care for their child, even sharper. We really do look forward to these naughty parents getting their comeuppance at the hands of their precocious and clever daughter, Matilda.

6. Norman Bates’s Mother (Psycho, 1962)

Alfred Hitchcock’s adaptation of Robert Bloch’s novel is a notorious and brilliant masterpiece. It made an entire generation give up showering in favour of a bath, killed off its leading lady after a mere half hour, and was the first film to show a flushing toilet. But for all the film’s notoriety (remarkable in the restrictive Hayes Code era), it is especially so for its final, shocking twist.

Surely, over fifty years later, the world knows the “big reveal” of Norman Bates’ transformation into his mother. But even to this day, after repeated viewings, Norman’s psychological damage is disturbing. Hitchcock superbly implants an understanding of Mrs. Bates in our minds, though we never see her alive. We only know a figment of her by the snippets of anguished “conversation” Norman has with her in that famous, dilapidated home adjacent to the Bates Motel.

We think we hear a woman’s voice cruelly putting her son down, harassing him and making him emotionally fragile. That fragility — and Mrs. Bates’ stifling influence on her son – is evident in the parlour room scene dinner with Marion, where Norman snaps at Marion and defends his mother. We even feel sympathy for Norman and want him to succeed in covering up Marion’s murder in that shocking shower scene.

The spine-tingling element to this twisted classic horror film is that Norman’s psychosis is entirely based in truth. Norman Bates is based on real-life serial killer, Ed Gein. To reflect upon that horror is to confront the horrific notion that evil can be manifested through upbringing. The actions of a serial killer like Ed Gein and Norman Bates could be caused through cruelty, neglect and abuse of a child by their parent. Or maybe, as Norman says, “we all go a little mad sometimes”.

7. Ed Wilson (Natural Born Killers, 1993)

The word despicable is far too lenient to describe Ed Wilson. Played to sweaty, bug-eyed and slobbering perfection by comedian Rodney Dangerfield (in his only dramatic performance), Ed is the father of serial killer, Mallory (Juliette Lewis) who embarks on an extreme killing spree throughout Texas with her lover, Mickey (Woody Harrelson).

Oliver Stone’s jaw-dropping, provocative and wild approach to this blood-soaked story is a million miles away from subtle. Stone deploys a veritable arsenal of filmmaking techniques – black and white in internalised scenes; sickly green for a hypnotically woozy, crazed aesthetic; wild jump cuts; flashes to demon faces juxtaposed against advertisements for Coca Cola. This visual cornucopia is potent satire; highlighting how as consumers we are manipulated by media images and the sensationalised cult of celebrity that the news creates to glorify serial killers on our TV screens.

Stone’s controversial and satiric intent is especially uncomfortable, brave and raw in a scene when we learn about Mallory and her horrifying past. Stone shoots the family scene in the style of sitcom, replete with fake house set, broadly comic performances and a laugh track. Except that Mallory’s father Ed is an abusive, drunken pervert.

Stone veers towards exploitation (intentionally so) when Ed’s disgusting, sexually leering “performance” is played for (and receives) audience laughs. As Hitchcock did with Psycho, Stone is making the point that the abuse Mallory suffered at the hands of her father, and the length of time she endured it, created the killer she would become; inflicting death against all men for the sins of her father.