In the beginning decades of cinema, there was no set language, no decided poetry, and no formal structure or grammar in filmmaking: there were no rules. The Lumière brothers experimented with realism (“Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory” (1895)), emotion (“Train Pulling into a Station” (1895)) and colour (“The Serpentine Dance” (1899)). Georges Méliès, another avant-garde filmmaker, trained his focus on narrative (“The Haunted Castle” (1896) and surrealism (“A Trip to the Moon” (1902)).

It was not until Edwin S. Porter’s 12 minute short, “The Great Train Robbery” (1903), that cinema starting developing its basics, such as cross-cutting and composite editing, which are now staples in filmmaking.

Once these rules were made, they became ingrained in filmmaking culture, championed by the likes of D.W. Griffith, Charles Chaplin and Sergei Eisenstein, all of whom developed cinematic tradition in many ways.

This list will be about the films by directors who rejected the ideals of their contemporaries by challenging the norm, or completely disregarding it.

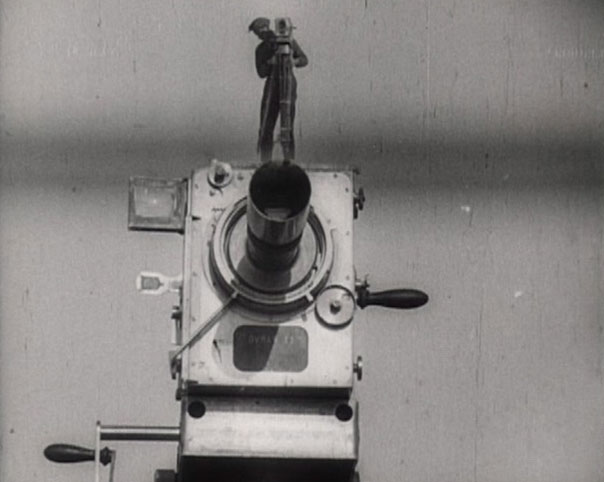

20. Man With a Movie Camera (1929)

The documentary’s documentary, the epitome of observational filmmaking, and sometimes regarded as the greatest achievement in the history of all documentaries, “Man With a Movie Camera” (1929) is no film to be taken lightly. Although director Dziga Vertov would otherwise make countless forgettable propaganda films, this effort midway through his career is not diminished.

With no sense of plot, no major characters or development, the film is a simple one: a documentation of a Russian city. Such a basic idea avoids the possibility of being weighed down by convoluted plotting or biased politics, and the result is a remarkable study of everyday life in 1929.

This exercise in social realism has never been repeated to quite the same level of success, though it is often imitated. This film breaks the rules of conventional cinema by barely qualifying as a film; rather, it is life in 1929 Russia, distilled on celluloid.

19. Oslo, August 31st (2011)

Rapidly gaining a cult following, acclaimed director Joachim Trier’s film is a realist study of drug addiction. Using a similar style to Agnes Varda’s “Cleo from 5 to 7” (1963), following the protagonist through a series of everyday encounters, the film compiles a comprehensive look at the disheveled character, Anders (Anders Danielsen Lie).

The film is bleak, though insightful and profound. The contained style of the film, all set over the course of one day, has been experimented with and mastered by some arthouse directors, though this style often comes first to the substance of the film.

In “Oslo, August 31st” (2011), however, a transcendental take on drug addiction counterpoints the understated, minimalist structure of the film. Probing into the mind of Anders with such conviction and unexpected efficacy, whilst avoiding contrived morals and melodrama, is so delicately handled that it eschews mainstream conventions and feels completely natural throughout the whole film.

18. Bicycle Thieves (1948)

The term “Italian neorealism” is thrown around a lot when describing a lot of social realist films nowadays, as gritty cinematography and down-to-earth characters with realistic problems are commonplace in cinema. Never was the case preceding “Umberto D.” (1952) director Vittorio De Sica’s “Bicycle Thieves” (1946). The now heralded classic was a groundbreaking cinematic endeavour upon its release.

Unlike many of the films on this list, “Bicycle Thieves” was almost instantly appreciated as one of the all time greats, topping the prestigious Sight and Sound greatest film poll of 1952.

17. Jules et Jim (1962)

Sometimes labelled the masterpiece of François Truffaut’s extensive oeuvre, it is also his most paradoxical film. Utilising tropes that would come to define his films, “Jules et Jim” (1962) features an array of filmmaking techniques that give the film a light quality, such as montage, narration and sentimental sequences fuelled by cheerful music.

Despite these, the dialogue and character relationships strike the right balance to propound a deep melancholy in the story. The film is made like a shallow romantic comedy, but achieves deep emotional resonance.

“Jules et Jim” is the story of the friendship between two young adults, Jules (Oskar Werner) and Jim (Henri Serre), and their emotional turmoil when presented with a ménage à trois of dissatisfying proportions. Neither of them want to share Catherine (Jeanne Moreau), though neither of them is enough on their own to hold the interest of the turbulent Catherine. As well as using conflicting styles of filmmaking, the film was sexually transgressive at the time, challenging and changing cinema forever.

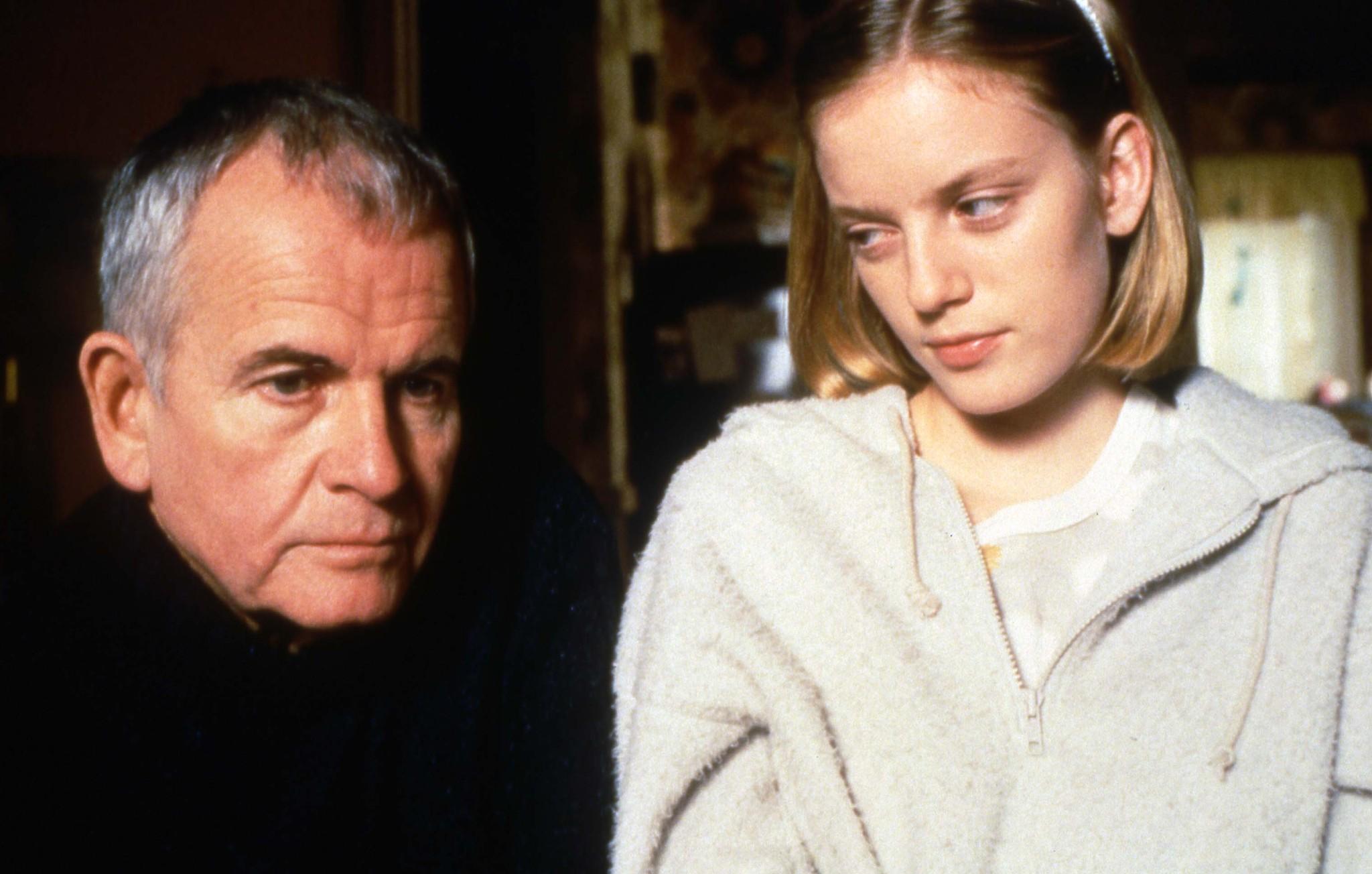

16. The Sweet Hereafter (1997)

Reverse-chronology became big after Christopher Nolan’s “Memento” (2000), bringing the plot device to the fore of the film. In “The Sweet Hereafter” (1997), however, the reverse-chronological structure of the film is seamless and so natural that it is near unnoticeable.

The film finds a small town rocked by a harrowing accident in the form of a school bus crash. The members of a once tight knit community are at odds with each other, some blaming the bus driver, others faulting the weather. The community is partly pulled closer together, and partly torn into bitter disarray, arriving at an uncertain conclusion.

Directed by Atom Egoyan, this Canadian film features standout performances from Sarah Polley and Ian Holm as tragic and conflicted characters. The depth of their inner conflicts are never quite revealed until the film’s finale, which is chronologically the beginning of the story. “The Sweet Hereafter” avoids the potential confusion that this plot structure could collapse into, displaying the deftness of Egoyan’s direction.

15. Polyester (1981)

Any film that automatically renders the image of the infamous “Scratch-n-sniff” cards ought to be recognised in a list like this. To be entirely honest, John Waters’s entire oeuvre could compile this list, though “Polyester” (1981) is his most fully realised. Waters has made a career out of eschewing convention, and this film is his least conventional yet.

The film finds a housewife, Francine Fishpaw, played by Waters regular Divine, as she uncovers her pornographer husband’s multiple affairs, her teenage daughter’s pregnancy, and the growing suspicion of her foot-fetishist son’s involvement in the recent crime spree centred on breaking the feet of local women.

Fishpaw’s world is crumbling amongst colourful, creative and repugnant characters. Loaded with criminals and disrepute, Waters manages to create real sympathy for Fishpaw, somehow creating real, honest emotions in the most artificial of worlds.

14. Dogtooth (2009)

The film that shot Yorgos Lanthimos to international attention, “Dogtooth” (2009), is a seminal film in a unique career. Though some critics found the characters and plot to be underdeveloped and overly bizarre, many have championed the film’s minimalistic approach and cited it as the harbinger of a Greek New Wave of sorts. Though there are noted criticisms, these are marginal in comparison to the praise the film has received.

“Dogtooth” is about a couple who have imprisoned their children within their estate under the guise of protective parenting. The children are unaware of the outside world and put all their trust in their parents, who guide them through life with lies and bizarre tenets.

For example, they teach their children that cats are deadly creatures that killed their brother who supposedly lived in the outside world. This “lesson” teaches the children that the world is a dangerous and terrifying place. Ideas like this make the film very unique.

13. Andrei Rublev (1966)

Tarkovsky elevated cinema to a new level of poetic awareness, changing filmmaking forever. “Andrei Rublev” (1966), his second film, was his first true foray into challenging and rejecting narrative conventions. Even today, his films have become no less difficult to understand, though repeated viewings can provide clarity, particularly in “Andrei Rublev”.

The film is divided into six chapters with a prologue and an epilogue. The main chapters explore several different aspects of the titular characters life, with varying involvement of the character; in one chapter he is altogether absent. The chapters are loose in connection and at times seem entirely arbitrary in their placement in the narrative.

However, when analysed, it becomes clear that their is an emotional arc to the film, and each chapter is designed to evoke these emotions. The film is not structured by story or characters, but rather by the oscillating mood portrayed onscreen.

12. Au Hasard Balthazar (1966)

Not many directors can make a film entirely about a donkey and keep the story entirely captivating for every second. “Au Hasard Balthazar” (1966) is Robert Bresson’s crowning achievement in a history of minimalistic, honest films. On top of being unremittingly captivating, the film has also gone down in history as one of the bleakest and most depressing films ever made.

The life of the donkey, Balthazar, is explored, as it goes through torments and mistreatment, the film is considered very similar to another popular Bresson film, “Mouchette” (1967). Apart from shattering the axiom, “never work with animals”, the film is so stark and seemingly limited by its minimalism and use of a donkey as a lead, yet the emotional depth is never in question. “Au Hasard Balthazar” is a tragic film that defies expectations and is never dull.

11. L’Age d’Or (1930)

Director Luis Buñuel was no stranger to absurdity by the end of his career; his confused detractors had thinned over the years, becoming familiar with Buñuel’s work and coming to understand it, and some of his fans had become tired of following a man who sought to confound.

On top of this, filmic legend and avid Buñuel consumer Ingmar Bergman conceded that Buñuel became a repetitive director. Despite his final tendencies towards the predictably bizarre, Buñuel’s first feature length film shocked audiences and transformed cinema.

Lesser known than his earlier short film, “Un Chien Andalou” (1929), “L’Age d’Or” (1930) is Buñuel’s initial foray into social satire, blending the surreality of “Un Chien Andalou” and his own real life experiences. Being about the relationship of a couple who try to consummate their marriage but are constantly thwarted by bourgeoisie society, the film prefigures Buñuel’s most famous film,

“The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie” (1972), with similar themes. “L’Age d’Or”, other than creating surrealism in filmmaking, was also ahead of its time in sexuality, being deemed outrageous and offensive for a scene that insinuates fellatio, as it is performed on the toe of a statue.