Every now and again, a film is released where we witness the magic of a new performer. It takes a level of bravery and a commitment through uncertainty for a director to cast young, unknown actors. More often than not, at such an early age, these actors are inexperienced. That’s why it’s so impressive when child actors are thrown into adult situations and deliver remarkable performances.

Most of the films listed below have children in substantial, principal roles. It adds to the astonishment of a talented youth when their responsibility is to carry the film. Moreover, the performances below aren’t intimidated. They’re largely dealing with difficult themes: loss of innocence, absence of family, grief, or destitution. They convey such themes with a lot of nuance and tact.

About 1/3 of the list centers on a child during or directly after a war. These films are taking the regularly subservient and callow presence of a juvenile, and making them come-of-age in the most extreme of circumstances. Some of the other films explore how children can find the courage within them to survive a bleak and battered environment.

Please note the list below is ordered chronologically.

1. Rinaldo Smordoni in “Shoeshine” (1946)

The director, Vittorio De Sica, is known for his neorealist films that centralize on social issues, using non-professional actors and genuine locations. Shoeshine is about two boys, played by Smordoni and the similarly great Franco Interlenghi, who are impoverished by postwar Italy.

Despite their economic struggle, they remain resolute because of their friendship and loyalty to each other. When they’re sent to a reformatory—a provisional prison for juveniles—their relationship becomes rattled and strained in the face of systemic corruption and betrayal. They lash out against the other crummy inmates who seem, for no good reason, to want to tear apart their friendship.

Smordoni is the brawn between the two, and the officials treat him better because of his slightly higher social status. But his performance slowly peels away to reveal the sadness and regret behind his tough exterior, making it all the more emotional when he’s met with tragedy.

2. Enzo Staiola in “The Bicycle Thief” (1948)

Vittorio De Sica’s most famous film is another from the neorealism movement. Enzo Staiola plays Bruno, the son of Ricci, who scrounges for a job. Bruno’s character helps add a little charm to this somber classic.

Viewers ride on the emotional wavelength of Bruno, who looks up, doe-eyed, at his father with alternating awe and sorrow. He innocently appreciates his father’s small triumphs, like getting a bicycle or eating at a restaurant. But he also bears witness to his father as he succumbs to economic strife and the shameful consequence of his desperation.

Staiola never plays the role too cute. Instead, he rounds out the rapport between him and his parent, which is essential for the ending to have its parable-like impact.

3. Brigitte Fossey in “Forbidden Games” (1952)

René Clément directed this timeless film, which focuses on the deeply moving journey of little Paulette, played by Brigitte Fossey, during WWII. After just having lost her family to the Nazi bombings, Paulette wanders around until she befriends a young boy, Michel, and moves in with his peasant family. Georges Poujouly plays Michel with sincerity and compassion.

Fossey was five when she filmed Forbidden Games, and later recalled her control to cry more or cry less, depending on what Clément wanted. Her face often bubbles with tears, but only when she’s away from Michel, her seeming savior. Paulette is entranced by the little games they play, especially when tending to their cobbled-together cemetery for insects and small animals. Her innocence doesn’t wane immediately after her family tragedy, but hits when her imaginative way of coping is taken away.

This makes her journey even more devastating. Poujouly a few years later played the car thief in Elevator to the Gallows (1958). Fossey later appears in Going Places (1974), a role that you have to see to believe.

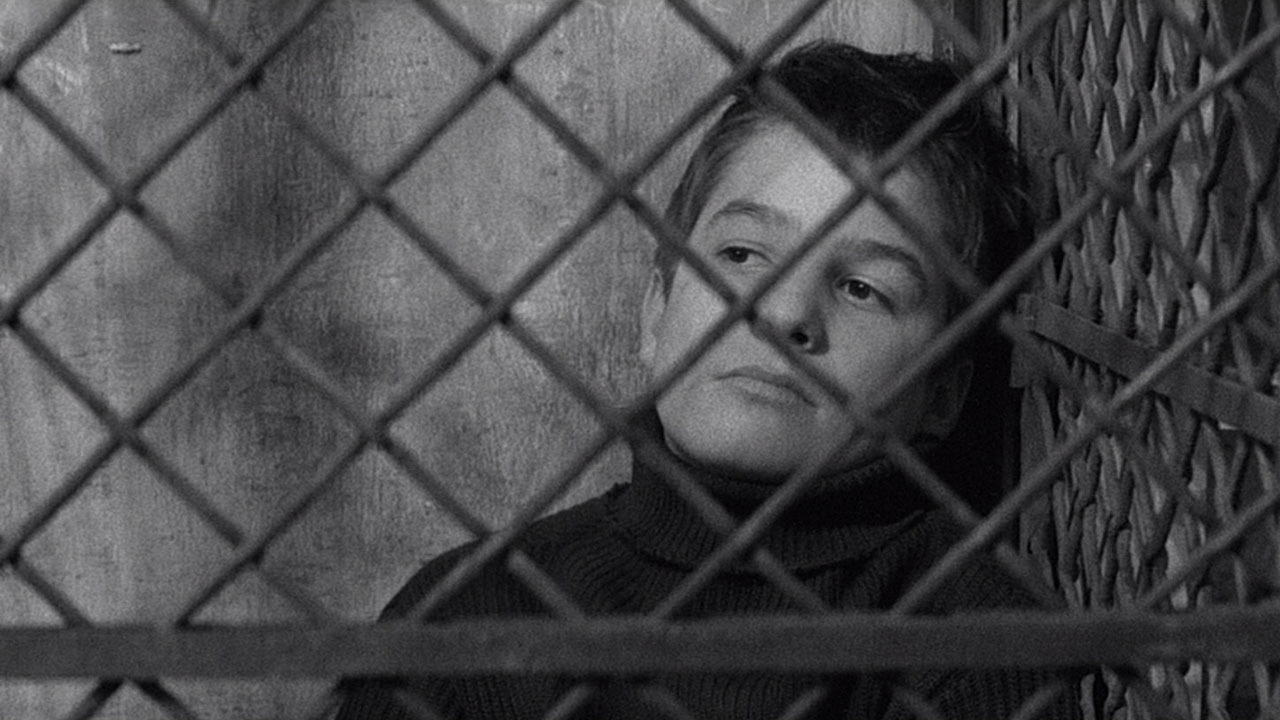

4. Jean-Pierre Léaud in “The 400 Blows” (1959)

One of the quintessential films of global cinema, The 400 Blows was not only pivotal in the birth of the nouvelle vague, but was a hugely influential study of a juvenile delinquent. It also began the close collaboration of Léaud, who plays Antoine Doinel, and the director, François Truffaut, who went on to make five films featuring this character, who is full of contradictions.

Antoine constantly lies, but he sees nothing wrong with that. His skewed logic comes from the void of guidance in his life. He rebels against what he views as an oppressive educational system and botched home life.

The scene where the psychiatrist questions him is a testament to Léaud’s performance. The scene, told from one angle, captures his intelligence as well as his misguided sense of the world. His dour visage masks what’s behind the surface—a lost soul, out of place, with nowhere to go. He fidgets his hands and smirks abashedly when asked if he’s a virgin. He has bold intentions but remains a fickle child.

In the end, Antoine runs to the end of world, and feels utter freedom, but doesn’t realize the consequence of his rebellion is complete isolation.

5. Martin Stephens in “The Innocents” (1961)

This superbly crafted gothic horror was co-written by Truman Capote, based on the novel The Turning of the Screw. It also contains a brilliant and unsettling child performance. Martin Stephens plays Miles, one of the children to be looked after by a newly recruited governess, played by Deborah Kerr. The black-and-white CinemaScope aptly covers this Victorian setting, and allows for the performances to thrive at the center, while obsidian ghosts lurk at the corners of the frame.

Miles returns to the mansion abruptly after being expelled from boarding school. Prepared for the worst, the governess is surprised when he arrives, finding him to be incredibly conscientious and charismatic.

Stephens’ performance begins delicately but grows to be more and more insidious. His role is slowly implicated little by little with disturbing detail, from a glance to the governess, to the chilling recital of a poem (“Gone is my lord and the grave is his prison”). Martin Stephens also had a decent role in Village of the Damned (1960) as a terrifying, telepathic kid.

6. Nikolay Burlyaev in “Ivan’s Childhood” (1962)

Andrei Tarkovsky’s debut, and most accessible film, features a boy who boldly takes on WWII as an amateur spy. Having lost his family to the Germans, Ivan is fueled by revenge, and steamrolls through war-torn landscapes with reckless abandon.

Burlyaev needs to play the role fearlessly, as he’s the courageous spy among older, trembling comrades. Because he meddles with adult affairs, he’s treated with a similar harsh reality. And it’s a testament to the actor’s control that he doesn’t cower. He wants to avenge his family, but still feels the brunt of their loss in a few emotionally charged scenes, which he handles with the maturity of an adult.

A year before, Tarkovsky was still a student and directed a short film (“The Steamroller and the Violin”) about a little boy who intensely practices his violin instrument. The result is quite different, tonally, from Ivan’s Childhood.

7. David Bradley in “Kes” (1969)

In the squalor of Yorkshire, England, lives a young boy, Billy. He’s the runt of his classmates, none of whom treat Billy with any respect. Due to his low societal status, he has a difficult time moving up in the school system. He doesn’t find any repose at home, as even his family treats him awfully, brutishly. Billy finds the calm and comfort he deserves only when he’s with his pet falcon.

David Bradley’s performance is tremendously raw, full of intuitive feeling. He’s pitted against every obstacle imaginable and outlines his character with an unbending diligence. There are times he looks so mucked and mangy (and alone) that you feel compelled to look up the actor to make sure he’s made it out okay. Ken Loach is distinguished for his social realism and often casts unknowns for a more natural touch. This unknown deserves the lion’s share of credit for making Kes a must-see film.

8. Tetsuo Abe in “Boy” (1969)

Japanese director Nagisa Oshima was considered the subversive answer to Yasujirō Ozu’s equanimity. Oshima takes a simple narrative and adds layers of symbolism and experimental design around Toshio, the titular “boy.” He’s the son of a con-artist family, who put him in increasingly dangerous schemes (like purposely getting hit by a car, and pleading for money from the driver).

Not only does Toshio risk his life, he’s otherwise completely at odds within Japan’s pressured society. He’s often alone at the edges of the frame and Tetsuo Abe gives his character an attitude of rebellion. In one slow-motion sequence, he destroys a perfectly built snowman, madly, as if he’s tearing down the entire world.