“It’s no use talking to me about art, I make pictures to pay the rent.”

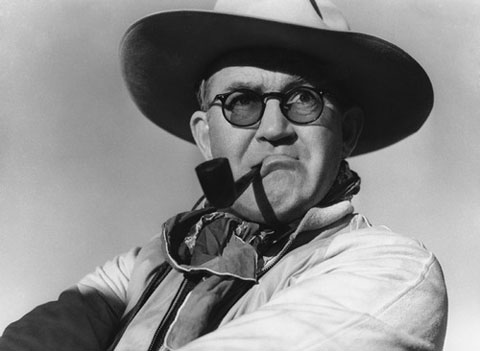

With all due respect to a legendary filmmaker, that famous quote from director John Ford is complete and utter hogwash. Ford may have been openly resentful of any analysis of his works and distrustful of intellectualism but his copious collection of films betrays a passion for cinema that all the Hollywood sheen in the world can’t bury. And yet there may be no director more acclaimed than Ford who remains more uncool.

It’s not uncommon to see the same modern day film schoolers drawn to the eccentric disposition of Orson Welles and overt intellectualism of Ingmar Bergman also dismiss Ford as a naff sentimentalist fit only to provide cheap nostalgia fodder. Nonetheless, the director was idolised by Welles, Bergman, Godard and just about every other respected auteur (with Bergman going as far as to name him the best director in the world).

Perhaps the difference is that Ford, even at his most artful, was never exactly ‘artsy’ – his films were as warmly unpretentious as their maker was socially belligerent and reluctant to discuss his work on any serious level. Of course, it may also be that after several decades of gritty revisionist westerns, Ford’s outlook on history has started to look a tad naïve.

It’s obvious from any one of his pictures that literal-minded documentation of the past was hardly the point. But while we could nitpick factual errors in his films all day, it is his habit of racial caricaturing that will likely elicit nervous collar-tugging in many a modern film fan.

The Native Americans generally got it the worst (a problem that Ford himself would admit in his later years). For every picture like Fort Apache and Autumn Cheyenne that offers a more sympathetic perspective on the Native American plight, you’ll find several others in Ford’s filmography that show us only a faceless, barbaric enemy, often undermining Ford’s frequent promotions of tolerance, community and compromise (of course, it also doesn’t help that regular star John Wayne has been quoted as saying some pretty appalling things).

In that respect, Ford could certainly be considered a product of his time. Yet to dismiss his work for its sometimes dated and underdeveloped depictions of certain groups is to dismiss not just his technical mastery but also the sincere compassion and insight that sustains at the core of his art, even if its context doesn’t always suggest the most informed of worldviews. Ford’s films were never meant to succeed on a historical level and they can be creaky, awkward creations on a sociocultural level but they can succeed spectacularly on humane, spiritual and political levels.

Anyway, onto the list. With more than fifty sound films and a good number of surviving silent features under the director’s belt, you wouldn’t be blamed for feeling that some real gems were overlooked in the culling process (here’s hoping the comments section will fill in the blanks) but the fifteen you see below should provide firm evidence for the unique artistry of one of American cinema’s greatest poets.

15. 3 Godfathers (1948)

Things start out simple enough in this Christmas-themed western, drawing you in with its vibrant Technicolor visuals, warm humor and an exciting bank robbery sequence. John Ford rarely threw an action set piece into his films so early in the running time but, in retrospect, it’s clear that this briskly established gunplay wasn’t intended to set the tone for the rest of the film but to get the combat out of the way quickly, establishing an early peak from which the titular trio can be gradually worn down.

Running out of water and wandering the desert with an increasingly vengeful sheriff on their tail, John Wayne, Harry Carey Jr. and Pedro Armendáriz stumble upon a dying pregnant woman and, from here, the religious symbolism shifts to the forefront. The old story of the three wise men is reborn as a tale of redemption and responsibility to the next generation, presenting a model of masculinity embodied by the nation’s fathers, rather than its violent gunslingers.

And then the film’s final third comes along and the picture takes a turn for the surprisingly dark, going one step further than It’s a Wonderful Life in its implications of Christmas Eve suicide. So 3 Godfathers is very much a film of three distinct sections, each of which are liable to turn different viewers off for different reasons but all of which bring something new and engaging to the table. Taken as a complete piece, it’s an unusually effective religious picture of secular relevance and a refreshing change of pace from the typical yuletide fare.

14. The Quiet Man (1952)

When Ford wasn’t indulging in the mythology of North America, he was doing the same for the old world. The Quiet Man sees the director going back to his Irish roots via John Wayne’s Sean Thornton and, since the filmmaker deals in romanticized memories, the country that Sean rediscovers is just how he left it, preserved in time. Of course, the Ireland of The Quiet Man has about as much to do with the real Ireland as Fargo does with the real Midwest.

Even How Green Was My Valley acknowledged that its nostalgia was for a Wales that no longer exists but the small fictional town of Innisfree is still the sort of quaint, spirited place where customs are paramount, alcohol and fistfights solve everything and a tearful woman will stop discussing her marriage problems to cheer on the catching of a big fish. Out of all the entries on this list, this is the one that looks and feels the most like an outright fairy tale.

That being said, to describe this film as any kind of ‘tale’ might be a little misleading. Ford had been valuing place over plot for a while already but, armed with a glorious new landscape to work with, The Quiet Man sees the element of story almost entirely edged out of existence.

With the euphoric buoyancy of a musical without the musical numbers, the film jumps between instances of romance and humor with the loosest of connections, save for the unifying themes of tradition, heritage and old-fashioned pride. You could say that this a film whose personality is indistinguishable from its substance. The stakes never feel particularly high but Ford’s gift for pacing and balancing of tones lets it all amount to something surprisingly potent.

The most wondrous sequences are those without dialogue between Wayne and love interest Maureen O’Hara. E.T. didn’t need to sample that famous scene of the two of them swept up in the winds of passion to make evident the influence that Ford’s dramas have had on Spielberg’s sentimental side.

Spielberg, however, has never possessed the same classical grit that runs through films like The Quiet Man and lends the picture a mature spirituality right up to its rapturous punch-up of a finale. Never has a film with so many spouse-beating jokes been this profoundly exuberant.

13. The Iron Horse (1924)

One of the highest grossing films of the 1920s, this silent classic is not your typical Ford blending of the personal with the historical. Clocking in at two and a half hours in its full version, The Iron Horse sees the artist go big with a grandly composed story of progress amid the absurd chaos of 19th century America.

Set before, during and after the period of the Civil War, the construction of the first transcontinental railroad is a coming together of the east and the west that parallels a coming together of the north and the south. The structure’s completion holds weight as a tribute to the nation’s big dreamers and as a testament to the power of a nation in cooperation, from the riders who travel 800 miles to bring cattle to the workers, to the workers themselves who span a range of nationalities.

Along the way, Ford shows early signs of his gift for lyrical, romantic imagery and charming details. The director’s films would become emotionally richer and more complex with time but The Iron Horse stands as a potent example of Ford using an abnormally large canvas to paint his vision of a changing nation.

12. They Were Expendable (1945)

Made shortly after Ford’s return from the South Pacific as a documentarian for the Navy, They Were Expendables displays levels of restraint and low-key ambition seldom seen in a Hollywood war film. The picture maintains an ongoing awareness of the large scale conflict, presenting frequent ominous and sorrowful reminders of the bloodshed taking place off-screen and elsewhere.

But Ford is much more in the mood for people-watching than wartime bombast, progressing towards the combat through a series of revealing micro-interactions. For the first third in particular, the meaning of solidarity in trying times finds expression in the film’s form as Ford remains, even by his standards, unusually democratic in his juggling of characters (this is that rare feature where even John Wayne can occasionally blend into the crowd).

It is through these patient methods that Ford deconstructs the nature of wartime comradery, showing how bonds must be quick to form and quick to dissolve amid an environment of death and dislocation. While every life has a value, this value is shown as one that can be grimly factored into military calculations of loss vs. gain. With bitter acceptance and perhaps even a little personal guilt, Ford reveals the inevitable tragedies that arise when cold strategizing directs human life and its expenditure.

11. Wagon Master (1950)

Wagon Master is the standard John Ford western in its raw and rugged form: no big name stars, no swooning romanticism, no larger than life hero, just straight up storytelling told at a relaxed enough pace for you to get to know the characters and for Ford to further explore his pet themes of violence, masculinity and the formation of communities.

The community in this case is a wagon train made up of an assortment of nomads and outcasts, the bulk of whom are a group of Mormons who choose not to carry guns on principle. Kicked out of their old town and searching for a fresh Eden at the end of a potentially hazardous route, the Mormons (arguably compromising on their ethics a little) hire a couple of armed horse traders to protect them.

Whereas Stagecoach drew a distinct line between the inhabitants of the coach and the dangers of the landscape they traversed, Wagon Master depicts the land as a place of hope, redemption, restoration and chance meetings. It’s a warm, accommodating post-war picture that looks forward idealistically to a time where weapons are no longer needed, while acknowledging how they may be a necessary evil in treacherous times.

And while treacherous times most certainly do come up in the form of a gang of sinister outlaws, action and bloodshed largely still takes a backseat to the rich, inclusive humanity of the film’s world. John Ford often cited Wagon Master as his favorite of his westerns and it’s easy to see why it’s so close to his heart. Rarely was he allowed to do what he does best with such little in the way of big studio flourish.