Editing is one of the most important steps in any filmmaking process, and yet, if it is done well, it will often be ignored. Hollywood taught us that a good montage was “invisible,” impossible to notice.

These 20 examples defied the idea of montage as a passive construction and instead developed techniques to make this aspect not only visible, but emotionally impactful. From mastering old techniques to bringing “mistakes” purposely to a scene, editing has developed and enlarged its codes through time. In chronological order, here are 20 revolutionary works in film editing.

1. The Great Train Robbery (Edwin S. Porter, 1903)

“The Great Train Robbery” features many of the early silent cinema codes. These films didn’t have the knowledge or consciousness of a wide variety of shots and angles and were, in fact, shot in studios, which necessitated minimal camera movement and virtually no close-ups. At the time, the act of cutting was a utilitarian narrative transition, merely a way to get from one scenario to another.

Porter’s film broke these rules. He shot outside of the studio and included camera movement in his shots. His main contribution, however, was in terms of editing. In these early films, all the action occurring in a scene was shot in that same scene: if the protagonist was running from a train, that “train” was in the same shot with him. Porter is the first registered case of dispensing with this traditional wisdom and employing cross-cuts.

Cross-cutting means to intercut actions on different locations, essentially enabling the film to show two different actions at the same time. Porter’s use was primitive, but it explains why the film was such a success in its time. Having two actions at the same time gave a new sense of thrill and tension. Porter presented for the first time what would be the basis for action cinema editing.

2. Battleship Potemkin (Sergei Eisenstein, 1925)

Some of the themes in “Battleship Potemkin” have aged, but its editing techniques certainly have not. A mandatory film for anyone studying montage, the great thing about the editing is how much Eisenstein himself wrote about his techniques.

He was a theorist as well as a filmmaker, and in his films, he put his theories into practice. He was even influenced by the works of Karl Marx. Marxist dialectic contributed to new editing techniques, which consisted of clashing two disparate images together to generate a new mental idea.

Eisenstein expanded upon these theories. He identified five different kinds of editing: rhythmic, metric, tonal, overtonal, and intellectual, and he employed these methods on “Battleship Potemkin.”

For example, he used meditative shots of ships (metric), but he also used a series of close-ups and wider shots repeated on a patron (rhythmic), and the intellectual method is obvious in the famous “Odessa steps” scene. Eisenstein’s influence is still salient today. Even if filmmakers do not directly credit him, his techniques are now so well-ingrained into filmmaking that they are impossible to avoid.

3. Napoleon (Abel Gance, 1927)

At a time in which it was uncommon to move the camera, Gance’s inventiveness is hard to believe. The film itself had many problems, largely because its length made it a difficult sell, but the issue was never resolved and there are now several versions of “Napoleon” available.

Most of these versions overlook the film’s experimental appeal at the time. Polyvision, for instance, was one of Gance’s inventions and it consists of three images from the same scene projected on three different screens. This new technique also made the film difficult to project.

Gance wasn’t shy about moving the camera, and there are a lot of innovative angles in the film, including some subjective shots from a horse, or from the point-of-view of a snowball falling. The same inventiveness was used in editing. Multiple exposure, split-screen, or even mosaic screen are first seen in Gance’s masterpiece. All these elements were combined with different levels of success, but the braveness of Gance’s decisions is still visible.

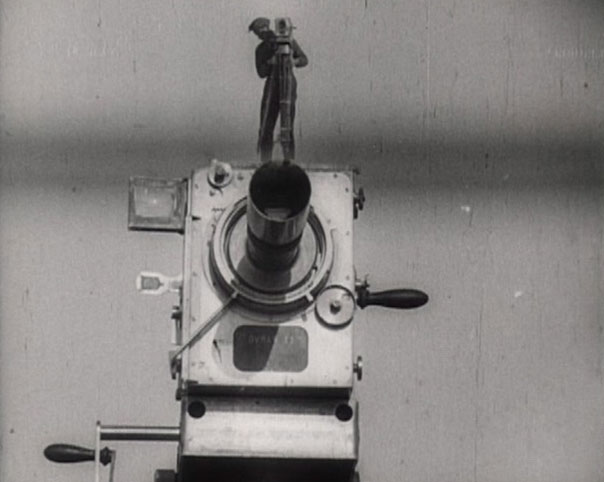

4. Man with a Movie Camera (Dziga Vertov, 1929)

Dziga Vertov and his wife Yelizaveta Svilova were two cinematic radicals. Fiction was the new “opium of the people”, and, according to them, their new “kino-eye” project was the only way to make real socialist cinema. Although he learned from Eisenstein’s theories, Vertov had one major issue with his films: the notion of narrative as the backbone of a film.

In Vertov’s film there is no narrative, but instead, the film is an enormous, abstract portrait of a city told through a montage of images of Soviet people working and performing routine activities. “Man with a Movie Camera” is not a film with groundbreaking editing techniques. It is a film in which the editing is everything. Instead of a run-through of random images, we have an intellectual exercise about a city and its political future told in the way the film was cut.

The film also used several special montage techniques, such as the use of double exposure, fast and slow motion, picture-in-picture, re-framing, stop motion, and backwards footage, among others. A lot of these techniques would later be credited as novella vague or praised in avant-garde cinema, but they were already here in the late 20’s.

5. Meshes of the Afternoon (Maya Deren and Alexander Hammid, 1943)

Deren’s collaboration with Hammid is still regarded as her most famous work. “Meshes of the Afternoon” is a later surrealist work, arriving almost two decades after Dali and Buñuel. Deren’s work has enough bravery and experimentation to prove its own worth, even if this extremely psychological approach didn’t have a lot of respect for space or character continuity.

For example, there is a shot/reverse shot between Deren’s face and a man, and then suddenly, another thing will replace one of the faces. In another scene, a mirror breaks inside a house, and in the next shot its pieces are falling on a beach. “Meshes of the Afteroon” is full of these weird ellipses where space and time are interpreted very freely.

Deren discovered how to achieve this through editing. She used the rough cut at strategic moments to change the background or character, but she also made thoughtful use of the swish pan to jump from one place to another.

There is also some pixilation animation, and Deren plays games with subjective camera angles. All of these techniques (and more) are displayed in 13 minutes in a short cut made in 1943, so it is easy to understand why her work is still so important.

6. Rope (Alfred Hitchcock, 1948)

“Rope” may seem poorly placed on this list, but there is good reason to consider it revolutionary. Consisting of only 10 shots and 10 cuts, the film was intended as something similar to a continuous long-shot. Most of the cuts in “Rope” are hidden: putting the camera in front of a black coat to block the lens, or going behind a piece of black furniture to make the cut unnoticeable, thereby tricking the audience.

This all came from Hitchcock’s mind. He established a new approach to editing: choosing not to cut is just as important as choosing when or how to cut. When the editing doesn’t come from the cuts, the viewer has to force himself or herself to complete the editing with his or her eyes.

Depth of field becomes more prominent and requires an active eye to understand what is going on. This idea was taken to the extreme on Sokurov’s “Russian Ark” (2002), and the influence is actually visible in the hidden cuts of “Birdman” (Alejandro González Iñarritu, 2014).