With the golden age of television looming large over not only modern cinematic practices but exerting an omnivorously outward reaching hand toward film directors like never before, the time seems right for a look back on the film directors who have, pre-fame or post-fame, looked to the smaller screen as either stepping stone or sabbatical from the intoxicating lure of cinema. Here are 15 instances, organized by show, of small screen projects that successfully found artistic certainty in the hands of past or future film directors.

Note: in an effort to broaden the list, preference has been given to often overlooked older projects. More modern television has been included only when a director has exerted a notable grasp over the material (directing multiple episodes or an entire season for instance). Thus, the likes of Martin Scorsese and Neil Marshall, usual shoo-ins for similar lists, have been excised for either older entries or more modern affairs with more singular directorial visions.

1. Alfred Hitchcock Presents; Alfred Hitchcock

Alfred Hitchcock patently redefined the state of classical cinema on multiple occasions, not only surviving the rise of the independent thrillers in the 1950s that savagely cut-down classical Hollywood’s reign but even seeing Classical Hollywood along through to the modern era himself with his singular melding of cinema’s past (his ruthlessly implacable formal precision) and future (his nearly avant-garde fascination with cinematic experimentation).

Due to this cinematic proficiency, it is often easy to forget that Hitch spent nearly as much of his most potent decade – the 1950s – in the television studio as on the film set. His anthology show – fittingly titled Alfred Hitchcock Presents for such an monomaniacal director – was a weekly outlet for terse televised anti-social behavior and dementedly warped social critique.

There’s a natural stylistic limit to television in the ’50s and 1960s, but the multitude of Hitch-directed episodes saw the master of the macabre loosen up a little and play around with the mores of the day in ways that transcend the literary origins of many of the stories.

For instance, “Lamb to the Slaughter”, Hitch’s most famous episode – and the most famous episode of the show altogether – boasts a winking screenplay by Hitch’s kindred spirit Roald Dahl, but the episode would be a paltry watch if not for Hitch’s playfully stagebound sitcom-style directing. In visually recalling the welterweight populist television of the day, Hitch twists the knife a little further into a story that gleefully imitates and perverts the golly-shucks Americana epitomized by the very sitcom style Hitch mocks in his framing choices.

Elsewhere, Hitch directs a stinging, cruel indictment of vigilante justice (“Revenge”), a palpably physical tale of the slow menace of stillness (“Breakdown”), a descent into unbridled malice (“The Perfect Crime”), and a cunning rural comedy (“One More Mile to Go”), all of which shake their head at society not with a slab of concrete but scalpel and Hitch’s trademark stalking-panther wit.

The extent to which the show barely hides its discontent toward conventional television niceties is bracing even by today’s standards; Hitch’s post-tale monologues openly mock the need for well-served justice, with Hitch dryly remarking in one episode that, although the killer seems to escape, “his dog was a detective in disguise and turned him in”.

The show is almost heretical, even anarchistic, in its debasement of the arbitrary qualities of televised happy endings, and elsewhere Hitch scabrously slams down the hammer on the very moral parable nature of the show, gloomily perusing a hall of potential morals and recalling that, no matter what, “one of them is bound to fit”.

2. Berlin Alexanderplatz; Rainer Werner Fassbinder

Almost definitionally less perfect than many of Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s more concise – and thus more conspicuously constructed – cinematic offerings, Berlin Alexanderplatz nonetheless feels like his magnum opus, and maybe his resting place. It wasn’t his final cinematic offering, mind you, but this made-for-German-television masterpiece from the cocaine-addled demon of the German New Wave feels like Fassbinder giving in, giving up, and laying his soul bare with a work perched somewhere between a dying man’s last breath and an adolescent’s first anti-social fit.

This 15 hour long polemic of contorted, interstitial growth and flatlining stagnancy, both personal and anthropological, personifies the descent from Weimar era pandemonium to Nazified fascist pseudo-clarity in the Germany public, locating all of the nation’s foibles and woes in Franz Biberkopf, a drone turned Nazi turned shell of nothing who appends masks to himself like a public looking for any external identity to dissolve or at least mask its internal inability to cohere as a people.

Fassbinder expends countless hours perusing Biberkopf’s internal vexations with a scalpel, and yet the sublimity of character belies Biberkopf’s fundamentally totemic status as stand-in for a nation torn apart at the roots. Perhaps this isn’t meaningful or even thoughtful anthropology, rooting an allegorical web of turmoil and political strife in the bleeding heart of one man with a trauma in his past. But it is, alas, intoxicating cinema with an undeniably rolling thrust of sheer detail and, importantly for any Fassbinder production, a surfeit of capital-A Angst.

Biberkopf’s constant exchange of identity is mirrored in Fassbinder’s countless, always reckless, often hyperbolic, occasionally jumbled and self-sacrificing implosion of stylistic trade-offs, jostling realism, deliberately presentational symbolism, impressionism, and, in the discomfiting two hour finale, out-and-out psychedelic horror show.

Berlin is prone to a meandering slacken quality, carrying little of Fassbinder’s usually intricate precision across its 15 hour trudge of clemency and dissent; stylistically and tonally, the mini-series is almost never in homeostasis, least of all in its misshapen fever-dream of a finale. Its imperfections are part and parcel with the sheer concrete-slab leviathan of oppression and character that makes up the mini-series, though.

Flawed as it is, brilliance abounds in Berlin, a work that intentionally shuns the clarity of character growth for a casual, funeral procession of ominously devouring insanity as Biberkopf, and implicitly the German people, lose their minds over a span of time that tellingly defies the notion of linear progress. It is not nearly Fassbinder’s most stylistically audacious work, but when it hits, even bricks are thrown by the wayside.

3. Breaking Bad; Rian Johnson

It’s no surprise that the television show du jour of the first few years of the 2010s could throw down with Hollywood when it wanted to. Nothing was stopping it from crashing Hollywood’s party. But with more than a little of its central character’s obsessive charisma and egomaniac swagger, it decided to throw its own party and invite Hollywood instead.

Rian Johnson swung around pre-A-list for the show’s most singular episode and returned for the after-party with two conclusive, concussive final-season episodes. But Johnson’s skill at balancing weighty thrills with existential woes – honed, Looper in the back-burner, by the final season of the show – has nothing on one of television’s finest bottle episodes, and the single greatest achievement of the show: “Fly”.

It is the double-edged sword of television that the expanded length, and thus the theoretical potential for probing sunken treasure in the little, out-of-the-way moments of human life that cinema doesn’t have time for, is usually crushed under the all-knowing weight of the network ratings machine.

Put simply, if a show wants to attract a continued audience, it has to replace the in-between spaces with moment-to-moment bangs and a surfeit of event. What one loses are the interstitial regions: the time spent lingering, doubting, questioning, or more importantly not thinking at all, but simply surviving for another day or two in the everyday hustle-and-bustle of another-day-on-the-job.

For a show that hinges on a pair of inadvertent business partners, precious little time is devoted to the nitty-gritty of Breaking Bad: life as a meth producer. All the backroom deals and murders would be for naught without the good stuff, after all, and the heady rush of action, reaction, and consequence seldom afforded time for the show to simply wait around a little with its characters and sink into their shoes for an episode. “Fly”gives us what no other episode of the show does: a day on the job, a little lazy-day downtime that quickly evolves into a tactile, tactical two-character play where words mean less than silent physical gestures.

“Fly” attains a critical mass of congealed rolling thunder despite its ostensibly low-stakes circumstances. Johnson’s camera excavates the nooks and crannies of the lab, the forlorn spaces of barren décor that serve as the home base of so much carnage that unfurls across the Southwestern United States during the show.

And the camera too traverses the unspoken physical crevices of the character’s personalities, like Jesse Pinkman’s shell-shocked trauma, Walter White’s discordant monomania, or the malleable psychoanalytic hothouse that is the wayward father-son relationship between them.

When a fly weasels its way into the office, White’s anxiety, and his dictatorial ruling fist, both turn to 11; his inability to shut himself off, his reluctance to admit to the chaos of the world, his my-way-or-the-highway authoritarianism, never felt so immediate, omnipresent, and all-encompassing. This is the Breaking Bad episode you feeling breaking bone.

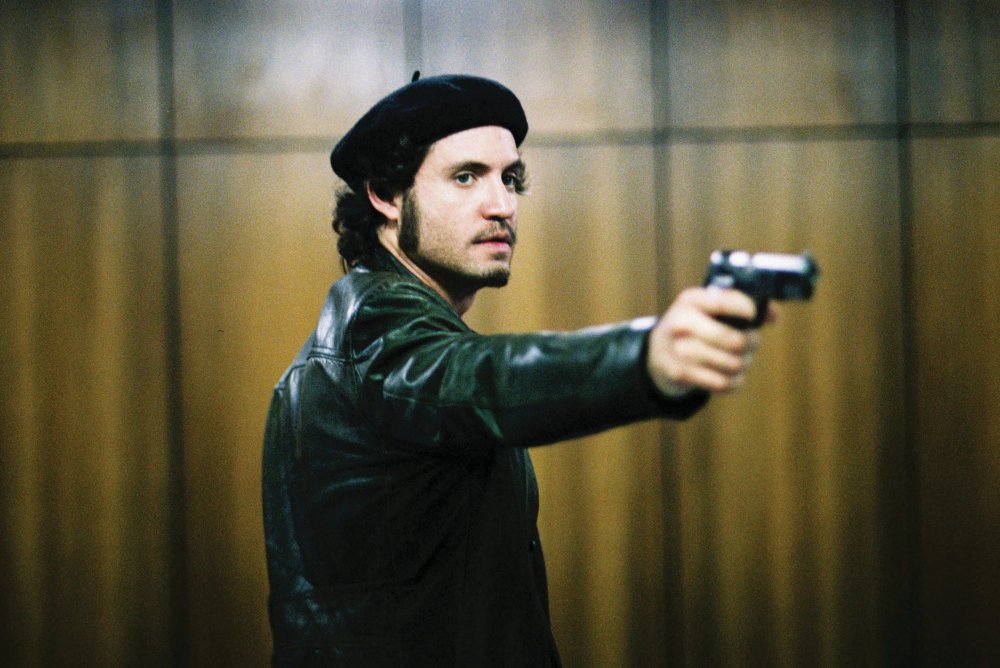

4. Carlos; Oliver Assayas

Oliver Assayas’ Carlos, a miniseries tracking the rise and downfall of terrorist troubadour Ilich Ramirez Sanchez (Edgar Ramirez), may have been made for television, but it sparkles with the bravado and swagger of classic live wire cinema. Yorick Le Saux and Denis Lenoir contribute hyperventilating camerawork and breathlessly maximalist cinematography that mixes glitz and grit into a hard charging revolution of a film, 5 ½ hours on the tin but a punch to the gut, a roller coaster, and a fever dream in effect.

All that the film reveals about Carlos the Jackal – the celebrity icon Sanchez pronounced himself in his early days – is secondary to its achievement as technically ambitious, mechanically bodacious cinema (Luc Barnier and Marion Monnier could not edit with more impact throughout, and the cuts seem to lose their mind as Carlos grows more insane with the cluttered web of conflict encircling him like a vulture throughout the film).

This is from-the-hip filmmaking that dives when you expect it to waltz, skips when any other depiction would march, gargles when lingering would be more coherent or respectable, and from beginning to end it never spends a second not fuming toward a cathartic conclusion.

Co-written with Dan Franck, Assayas’ film is his grandest and arguably most conventional, but he ameliorates charges of superficiality by down-tuning and upending the process-oriented story with an expressionist tilt located in his subject’s head: the rip-chord thriller that is Carlos is a hall of mirrors, all of them pointing not only at Carlos, but from within him. He sees himself less as an ideologue than as a cowboy, a male model, a punk rocker, or a Biblical figure with the coiled tenacity of a phantom and the sangfroid and staying power of a scarecrow.

His vision of himself is as action hero, and Assayas puts him through the motions of hero-dom until the action and the heat that satiates him end up destroying him. Edgar Ramirez, in a firebrand performance of tectonic malady, hedonistically envelopes himself in his own swagger until he suffocates on it.

Assayas’ series is character study of the highest order, showing us who Carlos is by becoming who he is, adopting his persona and pursuing his distinctly mercurial, temperamental nature. The ostensibly superficial, iconographic nature of the piece becomes a heartbreaking dissection of a man who views himself as a superficial icon.

5. Columbo; Steven Spielberg

Episodes of Columbo were necessarily cemented by scraggly Peter Falk’s whimsical, ramshackle performance as the titular detective, but the television-movie format of the material always afforded aspiring visualists a say behind the lens. Many of the best episodes are surprisingly experimental, especially the ones fixated on then modern technology and intrigued by the possibilities of introducing the technology to the celluloid medium. But one of the best, the first episode of the show in fact, is more drawn to the classical technology of the typewriter.

Nor does it hide this fact, opening with a bold zoom-out from a traveling car to a high-rise LA window and a writer furiously tickling the metal of his keyboard, the harsh, monochromatic metal of the businesslike piece cutting through the silence and making it all the more rusty.

The vertiginous ascent of the camera is exponentially uncomfortable, for one, but it pulls double duty in establishing the literal import of the man typing – he asserts himself above the city, after all – and the perfect symmetry of the man at the end of the zoom-out, blocked on either side by vacant windows of disinterested city life, already clues us into his individuality, as well as his lone wolf status.

A cut to a magazine cover boasting a pair of writers is a harsh contrast, and one that announces the central turmoil of the episode with nary a word: two men, a pair in public, are secluded souls in private, and the one doing the typing does his best work alone.

Nothing fancy filmmaking, surely, but it’s a masterclass in efficient storytelling. The filmmaker behind it: one Steven Spielberg, not nearly besting his sensationally riveting work with the television film Duel released in the same year but still announcing his presence, without sapping energy from the material at hand, right from the first scene. “Death by the Book” is about as nice an appetizer as you could ask for.

6. Decalogue, The; Krysztof Kieslowski

For the connoisseur of world cinema, Krzysztof Kieslowski’s Dekalog (The Decalogue, in English) must be confronted. For the late-blooming, early-to-the-grave director whose most fertile period lasted for less than a decade before his untimely death, Dekalog was not only a harbinger of things to come (his Three Colors are sometimes considered the defining films of the 1990s) but a domineering, tectonically oriented brew of the existential, the intimate, the epistemological, and the anthropological.

For a series nominally exploring the Ten Commandments, Kieslowski’s work is remarkably, breathlessly light on fire or brimstone, instead providing us an anthology of primarily humanist tales that don’t so much implicate as inquire. The open-faced nature of the piece, more focused on questions than answers, is epitomized in the introductory sequence, a primer for not only Kieslowski’s morality but for the fluid, malleable nature of film as it exists in the palms of viewers.

In the sequence, a boy’s father relies on a dogmatic disciple of reason – his computer – to statistically analyze whether local ice is safe enough for his son to walk on, but the entropy of the world has other plans. The dogmatic “Thou shalt have no other gods before me” is willed into a manifesto against dogmatism of any variety.

On dogmatic subscription to one style, Kieslowski heeds his own advice; this is a miniseries of “buts”. Kieslowski’s style is an insatiable question mark, often neo-realist but cocooning that neo-realism in an abstract, cosmic outer shell. An impressionist milieu permeates in the devoutly ugly color choices that malignantly invade corners of the screen, but the film is frequently subjected to traumatic expressionist bursts and seizures of dour comedy (witness how the light philosophizing of the first episode curdles into a shadowy wail of a horror film by the end).

Each episode is nominally tethered to a commandment, but several of the episodes apply to multiple commandments and some even contradict each other in a display of the messiness of life and morality – a fact that finds Kieslowski playfully questioning the very implication behind producing a television series “of” the Ten Commandments to begin with.

Most notably, it’s easy to reduce the show to a philosophical tract, but the piece is so lushly sensory in its imagery and distressingly intimate in its characters that it aims for the gut and the heart as well as the head. With nine cinematographers across ten episodes, Dekalog has long towered above conversations on world cinema. Yet it is no monolithic slab of unconditional cinema. It couldn’t be; it feels like a rejection of unconditional anything, or a celebration of conditions.

7. Knick, The; Steven Soderbergh

If we are truly entering a golden age of television, Steven Soderbergh’s The Knick may be a harbinger of bold, deliciously unsanitary directorial experiments to come, although hopefully it is more of a prelude than the main course.

The name Soderbergh looms large over this dissection of the flesh-eating circus that was the Knickerbocker Hospital in New York, and fittingly so; created and written by Jack Amiel and Michael Belger, The Knick’s writing is fittingly blunt but sometimes prone to fits and spasms of explanatory dialogue that undersell the hectic bottle-neck of racial and class tension unspooling amidst the technology and industrial revolution.

It is no Great Man biopic level failure, but John Thackery’s (Clive Owen) tale is sometimes perilously close to the classically-ordained “bitter racist is enlightened by black man, learns how to be a better person in the process” strain of Western individualist storytelling. Worse, the occasionally obvious, exsanguinated writing sometimes explores the foibles of Thackery’s character in a programmatic, “good Thack”, “bad Thack” fashion that is a little too Robert Louis Stevenson for its own good.

Yet unlike most television shows – where the creator or writer takes precedence – Soderbergh is the domineering iconoclast at the core of this drug-warped Grand Guignol of theater and performance in early medicinal practice and American life more broadly. Discounting numerous finite, single-season miniseries dotting television history, The Knick may be the most significant display of cohesive directorial bravura ever to grace the small screen.

Soderbergh was one of the first mainstream directors to experiment with the perilous world of digital cinematography, and here the hazy alienation of the medium abstracts the haggard labyrinth of backrooms in New York. The city is buckled into a hash-work of antiseptic, alienating aqua and feverish red interiors that almost single-handedly bend the geometry of idle place in New York into an unforgiving gutter of lost spaces.

People walk without purpose or determination, instead suffocating and stumbling around in a haze of opium-fueled delirium and manic-depressive viscosity; New York as a city feels both tangibly sensuous and otherworldly, like a vacant planar hell nonetheless occupied with enough sweaty, swampy human discontent to make the mere act of standing up a belabored struggle.

The chilly apprehension and shredded panic attacks of the toxically decadent synth score stabs into the characters like a scalpel into an abdomen in a show that perilously, dangerously slides from spectral, nihilist noir to European cinematic horror show. With Soderbergh at the helm, the potential sentimentality of the tale is vacuumed away, leaving a show that can take the form of both zombified cadaver and live-wire slug-fest.

Period pieces on both the big and small screens are often markers of respectable, staid technique and cloying stylist conservatism. The Knick’s period details are not merely period accurate; they are transcendent, not playing down to the time and place but applying that time’s physical features to introduce us to a more elemental human malaise.

Soderbergh isn’t merely transporting us a hundred years back in time; he’s becoming a void walker, and he’s taking us all with him. Call it an impeccable period-piece, but the show feels like a riposte to the arid qualities of period-piece fiction. In another of Steven Soderbergh’s sublime directorial shuck-and-jive moves, The Knick is the anti-Downtown Abbey.

8. Playhouse 90; Sidney Lumet, John Frankenheimer, Arthur Penn, and George Roy Hill

Television was simultaneously at its wooliest and most ascetic in the ’50s and ’60s, prior to the small screen even establishing an identity of its own outside of the cinema’s shadow. Playhouse 90 was the most overtly cinematic small-screen concoction during the early days of the medium, and fittingly, it served as a jumping-off point for not only future television writers (Rod Serling, most notably) but directors of the cinema such as John Frankenheimer, Sidney Lumet, Arthur Penn, and George Roy Hill.

Although none of the show’s episodes are likely to be confused for French New Wave style disintegration of cinematic girders, the TV-movie factory of Playhouse thrived as a surprisingly dexterous toybox for the equivalent of the non-auteur “studio directors” of the ’30s and ’40s in the more independent days of the 1950s and ’60s, when the studio system was in decline.

For directors like Frankenheimer, who directed 27 episodes of the show, the rough-and-tumble, scrappy settings were a showcase for a lean-and-mean, harshly clipped cinematic storytelling style that could ambidexterously flip-flop between noir, Western, melodrama, or any other kind of picture required for the week. The show was a little like a palette cleanser, with each episode beholden to no episodes but itself.

The terseness of the show proved a buttress for narratively-minded directors who knew how to stretch a budget, with the grimy immediacy of the low-budget quality serving as a counterpoint for the haughty pompousness of Hollywood at its most corpulent and self-important in the late ’50s and early ’60s.