The history of the Italian film industry is so rich that it makes these types of lists quite difficult to write. Although I have the opinion that after 1980, Italian Cinema almost “died” and wasn’t able to renovate its staff, quality and influence.

I agree there are a handful of films quite worthy of attention in the 90s; the industry itself completely lives by its classics. For that reason and to increase the degree of difficulty of the list, this list only concentrates on the films released before 1980, so any comments asking me, “why isn’t Cinema Paradiso featured?” or any other movie, it’s because these are only from before the 1980.

I’d say this is a list of classics with over 30 years of existence since they were released. It tries to diverse featuring several genres: Commedia All’italiana, Giallo, drama movies, war movies, crime movies or neorealist movies, among others.

The Spaghetti Westerns were considered, but to be honest, most of the greats in that genre are English-language, and after their shooting they are dubbed in Italian. Still, some of them were considered. and at least one of them is mentioned in the short list below. Only ITALIAN-SPOKEN movies are featured!

1. Bicycle Thieves (Vittorio De Sica, 1948)

It’s De Sica’s greatest release, and many may contest me on that, but I’ll stand my ground on this one. It’s the most representative of Italian cinema and mixes a great contemporary depiction of Italy after the loss in World War II, but also has an emotional plot and exquisite performances.

Again, De Sica uses a child as the protagonist alongside an adult, mixing two different generations of life and suffering. The adult may represent the old life battling for survival in an unfair Italy, and the child is the symbol of good and hope, much represented toward the end of the film with the child playing a very important role in the father’s actions and consequent regret and salvation.

The most emotional component of this film is Italy’s “state of mind” and a high degree of humanity imposed by the father and son relationship, and by the simple fact that such a trivial object is so vital for the survival of one’s family. After a long search, a poor man gets a new job where a bicycle is a mandatory prerequisite.

Despite not having one, he buys a bicycle after selling a pair of sheets. After a few hours of work, the bicycle is stolen, beginning a long search with his son for the stolen bicycle. Its dramatic ending, dignified yet so difficult to bear, gives this release a sort of perspective of the post-war disaster Italy was living in those days.

2. Amarcord (Federico Fellini, 1973)

It’s, by far, one of the top comedy-dramas of all time and one of the most influential. It is Fellini’s best comedy and clearly one of most eccentric movies filled with a bunch of eccentric characters that may serve as symbolic for most of Fellini’s interpretations. It’s a highly satirical and intelligent account of fascist Italy, and contains a high degree of sexual content and innuendo that is symbolic in Fellini’s eyes.

Although classified as a comedy-drama, I personally find it to be a comedy with dramatic bits here and there, and even those comedic moments have a sort of magical humoristic flair that beautifies and aggrandizes this masterpiece. Amarcord contains also some autobiographical and somewhat surreal elements.

Titta is a young man who lives in the small town of Borgo San Giuliano, Italy. It is set in the 1930s with the rise of the fascist regime and autocratic powers. Mussolini is often mentioned, satirically, as a savior and beloved by most of the town. The story of Titta has seen by him and his view toward his family and set of strange and eccentric characters living in the town.

3. The War Trilogy (Roberto Rossellini, 1945-1948)

I emphasize the trilogy itself, although knowing the third film, “Germania Anno Zero”, isn’t Italian-spoken. For that reason I refer to it as the trilogy, especially as it gained enormous critical reception and attention from critics. Also, it’s one of my favorite ‘sagas’, mainly for its controversial and difficult theme (the war), but also because it was so courageously released and made in 1945, 1946 and 1948, being one of the first (or the first) series of movies to portray such a theme.

Rossellini’s genius plays a big part in this trilogy. He not only shows the reality of the war and its consequences, but also ‘builds’ some sort of hero in each of his movies, creating a spirit of hope in the viewer while never letting aside the true reality of the events.

Actually, “Germania Anno Zero” is my favorite movie of the trilogy and, not wanting to specify each one, I’d dare say that “Germania Anno Zero” shows a sort of innocence that the other two movies don’t have, or at least don’t appear to have.

The trilogy is seen as one of the greatest neorealist efforts, portraying the destroyed Italy like never before. “Rome, Open City” is his most successful release, both in storyline and plot, and occurs when the Nazis were starting to lose the war but still had a rational chance to win; then “Paisà”, which is divided into six episodes and occurs when the Nazis are losing the war to the Allies; and finally “Germania Anno Zero” (my favorite) which portrays the destruction of the war and its aftermath to the German people.

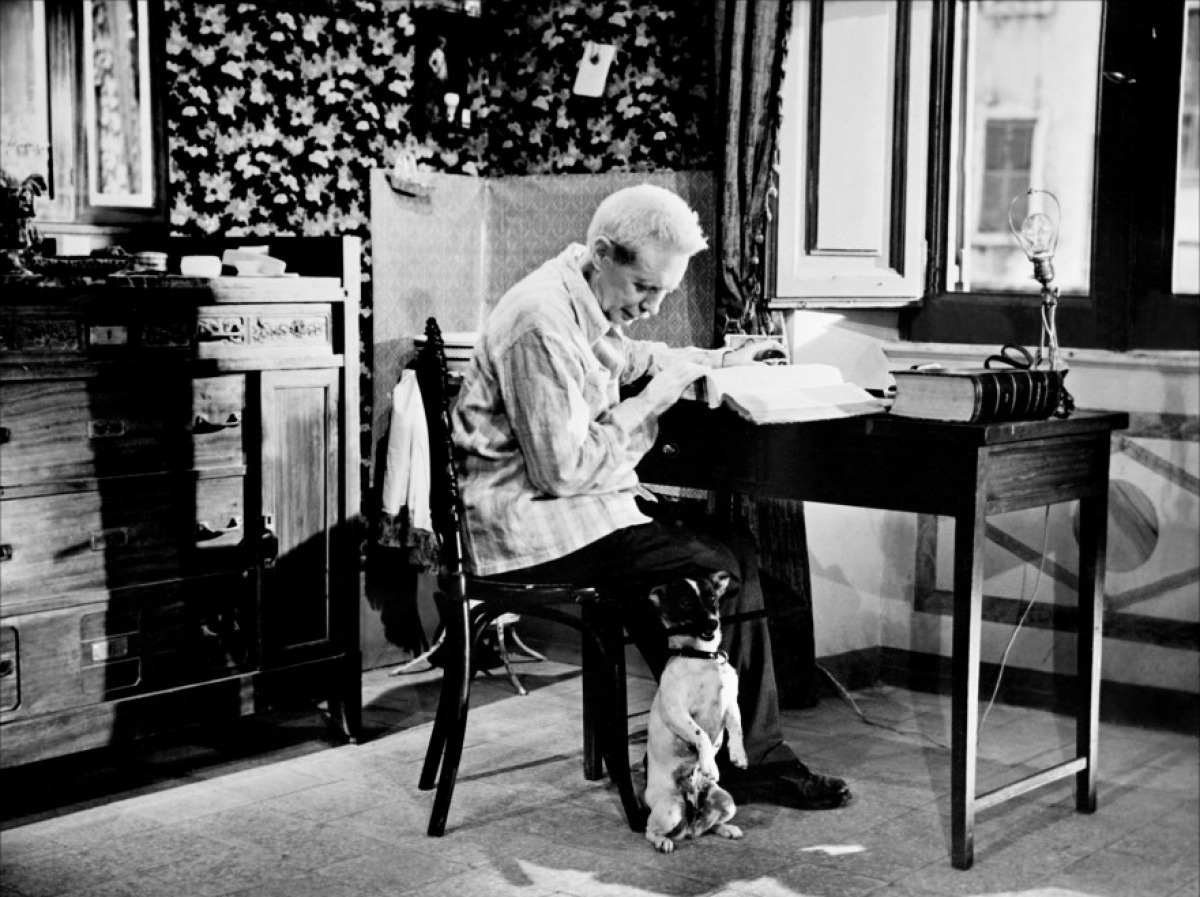

4. Umberto D (Vittorio De Sica, 1952)

It’s another one of De Sica’s releases on this list, where he dissects the worst in Italian society, not only for its treatment toward old people, but also for its lack of conditions, economically, socially and financially, in keeping a healthy nation where everyone could live happily and equally.

Also, the use of non-professionals elevates the movie, mainly in its performance and the quality of its acting environment. It’s widely regarded as a must-watch movie and a true favorite of most of the great directors of their time, including De Sica’s special favoritism for this movie.

It tells the story of an old man who desperately tries to maintain his room. He is in “open-fire” with his landlady and his only friends are the housemaid and his dog, actually maintaining a beautiful friendship with him until the end. De Sica’s genius is evident for the way he shows the contrasts, most evident toward the end.

It’s evident that the thought of committing such a horrendous act actually contrasts with his own personality throughout the movie, exposing the lack of will to continue, but also his own desperation. Also, the apparent innocence of the housemaid contrasts with her true reality. Her lack of help may denounce the unwillingness to help others, despite her seemingly true concern.

5. La Dolce Vita (Federico Fellini, 1960)

“La Dolce Vita” is still one of Fellini’s masterpieces and remains one of the greatest depictions of the Italian “sweet life”, much famous throughout the end of the 50s and 60s. It’s one of Marcello Mastroianni’s finest acting performances, and one of Fellini’s longest movies at 180 minutes.

It follows Marcello Rubini over seven days and seven nights. Rubini is a journalist for a gossip magazine, and it was in this movie that the word ‘Paparazzi’ became notorious and famous. The movie is structured in seven different episodes, divided into sections. The episodes depict the struggle for purpose, love and happiness of this seemingly occasionally out-of-place journalist.

It’s highly expressive and one of the most symbolic of the neorealist style. It may also be seen as a very strong critic to the so-called Italian jet-set full of glitter and glamour. I also see “La Dolce Vita” as a bit erotic, at least psychologically speaking, bringing one’s inner feelings out and exposing them to the world, despite his or her status in life.

The final scene is a great example of that; the famous, beautiful and blonde actress who redeems herself to Rubini’s infatuation; and the children exposed to some quackery stunt are some examples of that exposé. That is the worst side of the Italian “sweet life” often described as full of life, glitter and glamour. Fellini had the courage of criticizing that part of Italian life that appeared after the defeat in World War II.

“La Dolce Vita” was a highly censored movie for its highly graphic, expressive and realistic account of a forbidden and sometimes hidden life. Still, “La Dolce Vita” remains as one of Fellini’s greatest masterpieces, immortalized for its brilliant filming and structure, and excellent writing and acting.

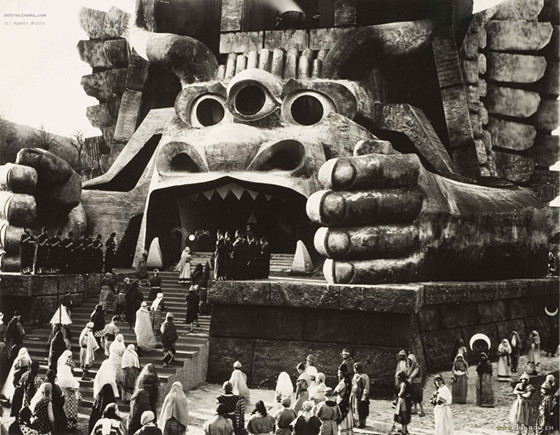

6. Cabiria (Giovanni Pastrone, 1914)

“Cabiria” is the only silent movie on the list, but it’s one of those movies I had doubts regarding its position. I even considered placing it in second place, due to its fantastic and stunning shots with amazing and realistic stunts that would be the envy of most movies shot after World War II.

It’s a highly influential film for many of the renowned directors of our time. Independent of its political influence, which helped the creation of the fascist ideals in 1914, the film is extremely important for the movie industry, both in Italy and rest of the world.

The movie deals with Italo-Turkish War, written by an ultra-nationalist, and therefore created some sense of fascist idealism, considering the fact it was released in 1914 in the beginning of World War I.

The film is divided into five episodes and mostly deals with the war itself, alongside the rescue of Cabiria, a little girl who was taken by Turkish extremists and has to be saved from their hands by a Roman soldier and his ever-trusting servant.

I highly recommend this release for its fantastic imagery and great action, while creating a highly involving storyline. Although the performances aren’t that good, the setting, wardrobe and visual effects are just perfect (10/10). “Cabiria” is one of Martin Scorsese’s favorite movies and the restored version was introduced by the director at the Cannes Film Festival in 2006.

7. Il Posto (Ermanno Olmi, 1961)

Nothing will ever change my idea about Domenico, the main character of this film. Although it was not the intention of the film, Domenico is a very “comedic” character, if you think about it. He portrays the typical Italian young adult who, thanks to the poor economic conditions of his parents, has to start helping them and making a living for himself by applying for a new job. He’s ambitious without showing it and falls in love with one of the other candidates.

The company he is applying to is industrialized and symbolizes the new Italy of the 1960s, which after the Second World War is starting its economic development. He almost never smiles and when I say he is a “comedic” character, it is due to the fact that he seems a bit lost and hopeless in his new conditions and situation.

The movie has its humoristic moments, despite being a dramatic movie. Olmi’s vision of a satirical Italy and its industrial future completely does the trick in this movie, completing the credibility of the film.

It is definitely a satire of the “job for life” ideal, contrasting with a young adult who seems to predict the situation in his future knowing he will be stuck to a desk for the rest of his life, leading the same boring and saturated life the other workers lead.