Every ten years, the British film magazine Sight and Sound asks critics around the world to choose their ten favourite films of all time. Everyone is familiar with the old warhorses that regularly show up in this poll – your Citizen Kanes, your Tokyo Story. But we forget that it was not always thus.

Time was when Pudovkin’s Mother and Flaherty’s Louisiana Story made regular appearances in such lists. Now they are all but forgotten. What’s even more intriguing is the films that creep up on those old classics and overtake them, films at first ignored or seen as mere entertainment, that build up a momentum of critical approval that snowballs into the declaration of a masterpiece.

Who, in the 1950s, would have thought that a Hollywood thriller, Vertigo, would eventually be crowned the finest work in the medium’s history? And in the modern culture of mass home media, with more and more movies being dug up to feed the burgeoning Blu-Ray and streaming markets, there’s always the potential that a film already many decades old – a contemporary of Louisiana Story, even – may be rediscovered afresh and take its place in the pantheon.

So let’s take a trip in a time machine and hop forward, say, 50 years to see which films already made, and which currently languish in the outer margins of cultdom or obscurity, could grow in appreciation and speak more strongly to an audience of the future.

1. The Borderlands (Elliot Goldner)

No classics of the future are so eagerly anticipated yet so difficult to spot as cult horror movies, those obscure delights which get seen in passing and make an unforeseen impact, which later builds into a shared point of reference for a whole generation.

In 2013, another candidate trickled out quietly across selected cinemas and was casually ignored – because it has the misfortune of being a found-footage flick. It’s a genre which has fallen foul of viewer fatigue – a great pity, because The Borderlands is actually the first film since The Blair Witch Project to really develop the format and make it an intrinsic part, not only of the “being there” experience, but also of the thematic development of the story.

It follows three investigators employed by the Vatican to research an a apparent miracle in an English country church. For the purposes of their inquiry, they must wear headcams to record all their evidence-gathering.

It’s terrifically scary – a rarity itself in modern horror cinema – but also warm and funny, with well-written interplay between the very different leading men. But where it really scores is in its exploration of the “seeing is believing” attitude towards faith, one investigator pointing out that pagan religions at least worshipped something that was demonstrably there.

The visual phenomena picked up by the camera therefore become signposts on a path to belief, leading to the ultimate revelation of Truth, in an ending so unexpected and so ingenious, it will have you believing there is life in the found-footage genre after all.

2. Bellamy (Claude Chabrol)

Chabrol’s last film plays like a Sunday night TV detective drama; in a cosy, gorgeously photographed corner of the French countryside, an amiable, respected police inspector (Gerard Depardieu at his cuddliest) gets involved in a case while on holiday, all the time suspecting his wife may be cheating on him with his wayward brother when he’s out on duty.

It all seems a world away from the spiky psychological thrillers with which the director made his name. And yet, there is a troubling sense throughout the narrative that we are not seeing the whole story, that really this is a tale told in its absent scenes rather than those witnessed; as the WH Auden epigram at the end has it: “There is always another story, There is more than meets the eye.”

In fact, the viewer is left reeling at the realisation that a seemingly straightforward tale might be wholly reversed in meaning and still be absolutely true. And so, an apparently quiet coda to an impressive career is revealed as being one of its most subversive entries, an enigmatic gem whose mysteries await discovery by a wider audience.

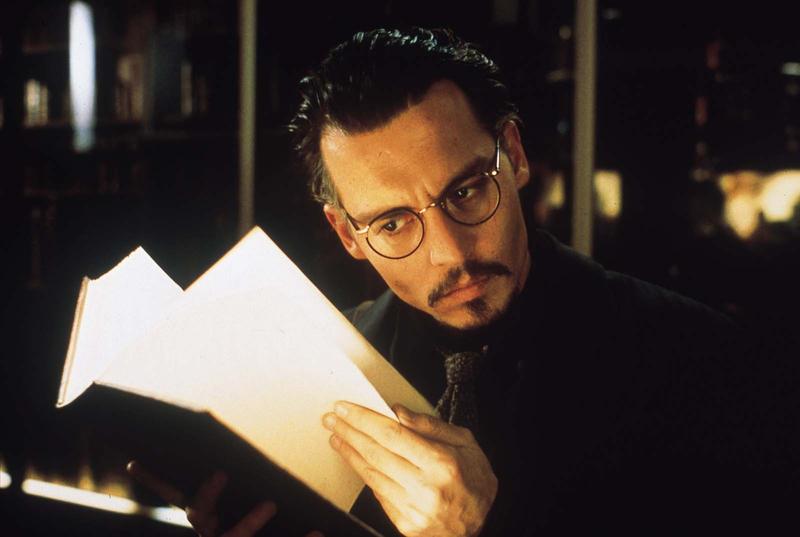

3. The Ninth Gate (Roman Polanski)

Polanski is, of course, best known for his work in the ’60s and ’70s, such masterpieces as Rosemary’s Baby and Chinatown. But will future generations be more interested in what John Orr described as “a millennium film…one of the most disturbing of cinema’s end of century features”?

The popular reputation of The Ninth Gate is of a kooky black comedy, starring Johnny Depp, that anticipates the daftness of The Da Vinci Code, in its tale of a bookseller tracking down copies of an ancient tome that, if deciphered, leads the reader to a meeting with the Devil, and which has Emmanuelle Seigneur as a succubus flying on Kirby wires and Lena Olin vamping it up in suspenders.

But it’s precisely Polanski’s taste for ironic humour that offsets the horrors within the story and prevents the whole collapsing into farce; because we are encouraged not to take it too seriously, there is no pomposity or po-facedness to puncture, and the aura of the occult remains intact.

The result is a film in which evil is relentlessly seductive, where the hero’s journey towards greater amorality feels like emotional progress rather than a temptation into darkness.

All complemented by one of the most haunting and criminally neglected soundtracks in movie history, the end-of-credits wordless aria powerfully evoking the strange beauty of corruption.

4. Zelig (Woody Allen)

When Woody Allen finally gives up his director’s chair and the prurient interest in his sex life dies down, only the films will remain, and future generations will rediscover Zelig as one of the great American allegories, a technical marvel years ahead of its time, and a coruscating self-portrait.

A pseudo-documentary about a man whose personality and even physique change according to who he’s with, it was seen by those who liked Woody as another amusing comedy, and identified by his detractors as a personal confession about his inability to cohere as an artist, forever copying Bergman or Fellini (which is possibly true).

But once “Woody” is removed from the equation, what is revealed is a sharp and very funny comment on modern liberalism, the cowardice of not confronting opposing views, of allowing everyone their reasons, no matter how heinous or ridiculous.

Put next to Forrest Gump, which it anticipates in its use of newsreel and old footage, it seems far more politically astute and cinematically nimble.

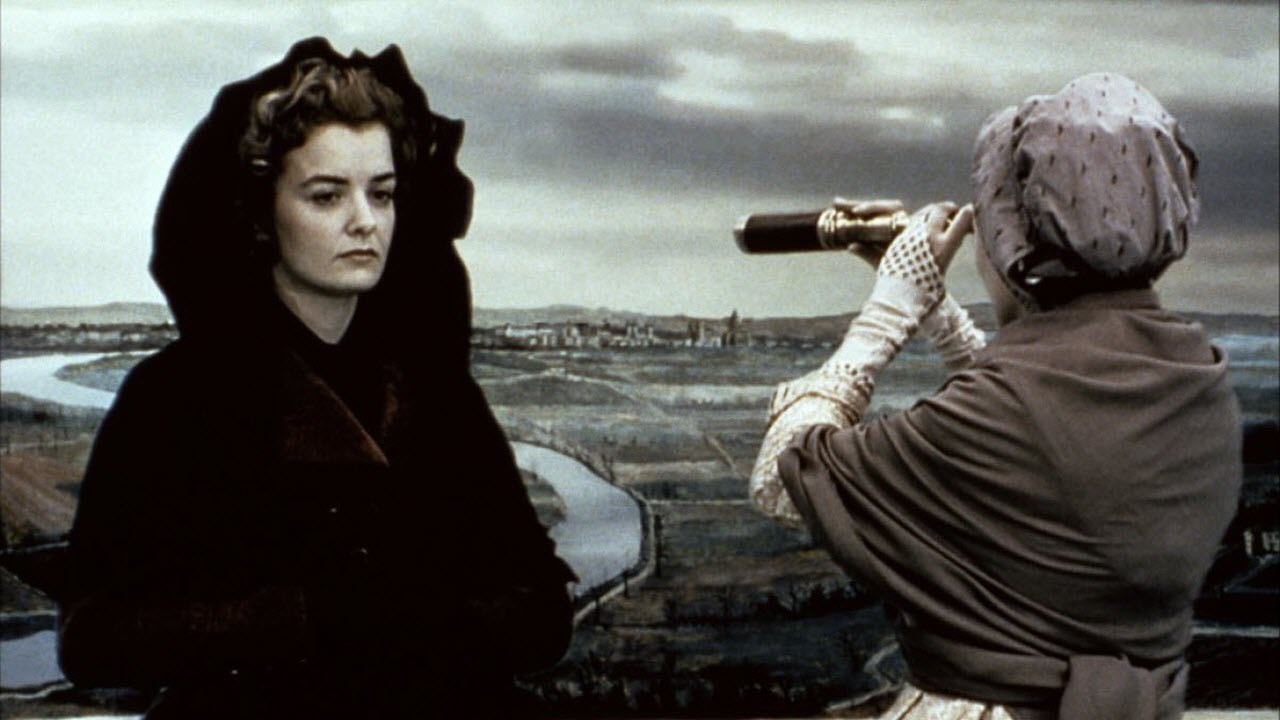

5. The Lady And The Duke (Eric Rohmer)

If a film archaeologist of the future were to look back over the early history of CGI and digital manipulation in movies, one would expect their main focus to be on the Hollywood blockbuster.

But it was Eric Rohmer, of all people, French purveyor of chatty relationship dramas, who provided one of the most stylish demonstrations of the new technology in this stunning period drama set during the French Revolution.

The story concerns a Royalist Englishwoman living across the Channel as the uprising begins, whose love for a pro-Revolution aristocrat puts both their lives in danger. Lucy Russell’s central performance and the intelligent depiction of social change at a time of political upheaval are reason enough to seek out this film.

But it’s the way Rohmer recreates the time, with digital backdrops based on paintings and maps, that should secure this film its reputation, and help prove that bravura technical progress belongs as much to the art film as it does to the multi-million dollar spectacular.

6. A Scene By The Sea (Takeshi Kitano)

Once described by critic, Tony Rayns, as having the best editing since Bresson, this film, like its director, seems to have vanished into obscurity. In the ’90s, Kitano was rated as one of the most important figures in new world cinema.

But even then, he was predominantly celebrated for his idiosyncratic take on the gangster genre, and so it was that this beautiful antecedent of the (depressingly named) Slow Cinema movement was largely ignored on first release.

The story couldn’t be more simple – a deaf-dumb boy wants to surf, he gets a girlfriend, he learns how to surf. Kitano instead concentrates his energies on his peculiar stripped-down style, razor sharp cutting, and innocent pathos mixed with schoolboy humour.

The result is a film that appears to be about virtually nothing, yet has a huge emotional undertow, and leaves the audience feeling they have absorbed more then they’d realised.

If rediscovered, it would re-establish Kitano’s reputation in a shot, and be recognised as one of the first steps towards an approach to film that has so far defined the 21st century arthouse.