By the 1960s, the golden age of Hollywood was dead and buried. The studio systems were failing, productions were not gaining as much clout as they had been in the war years. The image of the wholesome family entrenched in white picket fences and jaded happiness became stale and was reflected in the anti-establishment movements popping up all over the United States.

On top of the fall of the studios, the Vietnam war was in full effect by 1966 and through portable cameras was able to be broadcast worldwide, raising the ire of pacifists who would decry the violence and governmental mandates in foreign policy.

The decade saw the hippies, the Black Panthers, the homosexual movement and a new wave of feminism lead the public in various directions, allowing broadcasting and social gatherings to connect everyone nationally.

In the midst of this new page in history, the studios, under pressure to regain an audience, gave the keys to the kingdom to film students. Shirking the executive constraints of the studio system, these mostly young directors brought their knowledge of the greats and infused them into their own unique style, creating classics that have been both influential and iconic in their time.

In many of the productions, the influences of Godard and Truffaut, Rossellini and De Sica, Bergman, and Eisenstein ran rampant, giving the perfect amount of flavor to the productions. On top of the New Hollywood system, a series of underground and independent productions also were made, giving rise to genres explored by social groups and rights activists.

These productions also took the social disarray into account. Many films of the era (from roughly 1967 to 1980) reflected the times America was living in, creating metaphoric masterpieces that still hold socio-political weight to this day. It is through these films that this list is focused on.

Author’s note: Despite these films being labeled as icons and classics, they are not representative of New Hollywood cinema entirely, as some of the titles here are not deemed “New Hollywood” for their lowers budgets and disassociation with Hollywood itself. These are films from the era, not necessarily the institution of New Hollywood itself.

1. The Graduate (1967) – Mike Nichols

In 1967, two films marked the apparent start of the New Hollywood era in cinema. The first was Arthur Penn’s Bonnie & Clyde, a violent yet stylish mythologization of a gang of Depression-era bank robbers; the second was a polarizing tale of young ambition and confusion, delving deep into sexual liberty and the horrifying vagueness of what the future holds. From then on, Hollywood and American cinema would never be the same.

Labelling The Graduate as a starting point for the New Hollywood era is sometimes mired in controversy, but its lasting impact on directors of that time is present. It was a breath of fresh air in an era marred by studio traditions trying to keep an old system alive with outdated with an outdated formula giving rise to the New Hollywood auteur.

Both a mixture of bizarre drama and subtle comedy, The Graduate marked a turning point in the studio system Hollywood had traditionally underwent since its golden age.

With The Graduate, the unforgettable story of the young man trying to find himself in a sea of confusion and the pressures to make something of himself by elders and institutions was on the tip of the American youth culture’s tongues in the 1960s and even served as a great metaphor for where Hollywood cinema would go in the next 13 years.

Seduced by an older, well-established system, a younger generation managed to project their hopes and fears on the big screen, leaving an ambiguous uncertainty about the future, much like the young Benjamin Braddock in Mike Nichols’ landmark film.

2. David Holzman’s Diary (1967) – Jim McBride

Both a love letter to and a critique of cinematic obsession, David Holzman’s Diary, a faux-documentary about one man’s personal struggles with the need to chronicle his life, brilliantly captures the psychological distress of an over-ambitious artist while also perfectly taking a look at his everyday New York City environment.

Part-comedy, part-awkward drama, David Holzman’s Diary plays with the viewer’s perceptions in thinking it is really a story about a complete nutcase when the reality of it is more about one’s obsessions and inability to tell the difference between ambition and caring.

Despite not being an overt political film, the images of the gangly David Holzman attempting to document passersby on the sly with an oversized camera rig and recording equipment is at times ridiculous and uncomfortable. His drive is inspiring but also serves as his downfall, mirroring the struggles of many an artist in an age of mass production and the shrinking window of recognizable self-expression in the late-60s.

Despite the social pariah image of its protagonist, David Holzman’s Diary is a lesser-known but informative portrait of the obsessive filmmakers who would eventually emerge in the coming decade with equal amounts of tedious work ethic.

3. Night of the Living Dead (1968) – George A. Romero

Horror films have always had a political subtext behind their initial stories, whether it be the Red Scare, nuclear testing gone wrong, or general promiscuity. The underlying themes of horror cinema give the genre more weight through its metaphors. George Romero’s early low-budget zombie film is just one of those perfect examples of horror cinema that makes a political statement, firmly rooting itself in its historic time.

Set in rural Pennsylvania, the film takes place at the dawn of a zombie apocalypse. With multiple characters barricaded inside a large farm house, the chaos and confusion of what is happening and what to do is ever present. As hordes of reanimated corpses crowd toward the promise of living flesh to eat, the survivors are eventually picked off one by one either through valiant efforts to rescue their fellow victims or out of their own sheer stupidity.

Night of the Living Dead has added weight to its overall message especially since it was shot and released in 1968, a tumultuous year for the United States. A year of political assassinations, an escalation in Vietnam War carnage, and riots wrought havoc on major cities.

This film is a welcome compliment to the violent social climate undergoing one of the worst years in history. The shocking violence and disturbing content of Romero’s unique zombie film plays on the fears heaped upon the American people in such a dark age, questioning its values and abilities to cooperate with their fellow citizens.

Along with the themes of social fears, yet another political comment was made through the inclusion of African-American actor Duane Jones as the main protagonist of the film. His role as Ben is an excellent metaphor for America’s racial tensions in the 1960s. In a decade that saw the assassinations of two of Black America’s most iconic leaders, the eventual fate of Ben at the end of the film adds a lot of cultural importance to an otherwise independent production.

Ahead of its time and virtually untopped in its horror, Night of the Living Dead went on to become one of the most influential low-budget films ever made and allowed Romero to revisit his theme of zombies-as-political-statement ten years later with Dawn of the Dead.

4. Rosemary’s Baby (1968) – Roman Polanski

While Night of the Living Dead was an excellent low-budget horror film commenting of racism in the United States, Rosemary’s Baby took a subtler approach with the horrors of the unseen, giving a sense of paranoia that helped build into an era of distrust, degradation, and ultimately acceptance of the inevitable.

Despite its comfy interior, Polanski sets his horror film up as a melodrama issuing a generation’s dealings with marriage, careers, and social anxieties in their given time. However, Polanski shifts these themes on their heads when Rosemary, the wife of a struggling actor has a nightmare rife with political and satanic imagery.

Essentially sacrificed to the devil as a sex offering by her husband in order to further his career, Rosemary soon becomes pregnant with the Antichrist, and as the birth of the child approaches, Rosemary must make the choice of whether to destroy an evil that will be wrought upon the world or accept her motherly duty.

Polanski tells this story with expert precision by showing the audience next to nothing in regards to horror imagery. More like the ghost stories from the previous era, Rosemary’s Baby is subtle, but speaks about women’s liberation and the debate about abortion quite clearly.

The film also represents a naivety of 1960s culture breaking from the puritanical post-war culture that had been around for 20 years previous. A culturally significant film, Rosemary’s Baby proved to be one of Polanski’s outspoken masterpieces, made even creepier by the shocking murder of his wife Sharon Tate merely a year later by the Manson family.

5. Faces (1968) – John Cassavetes

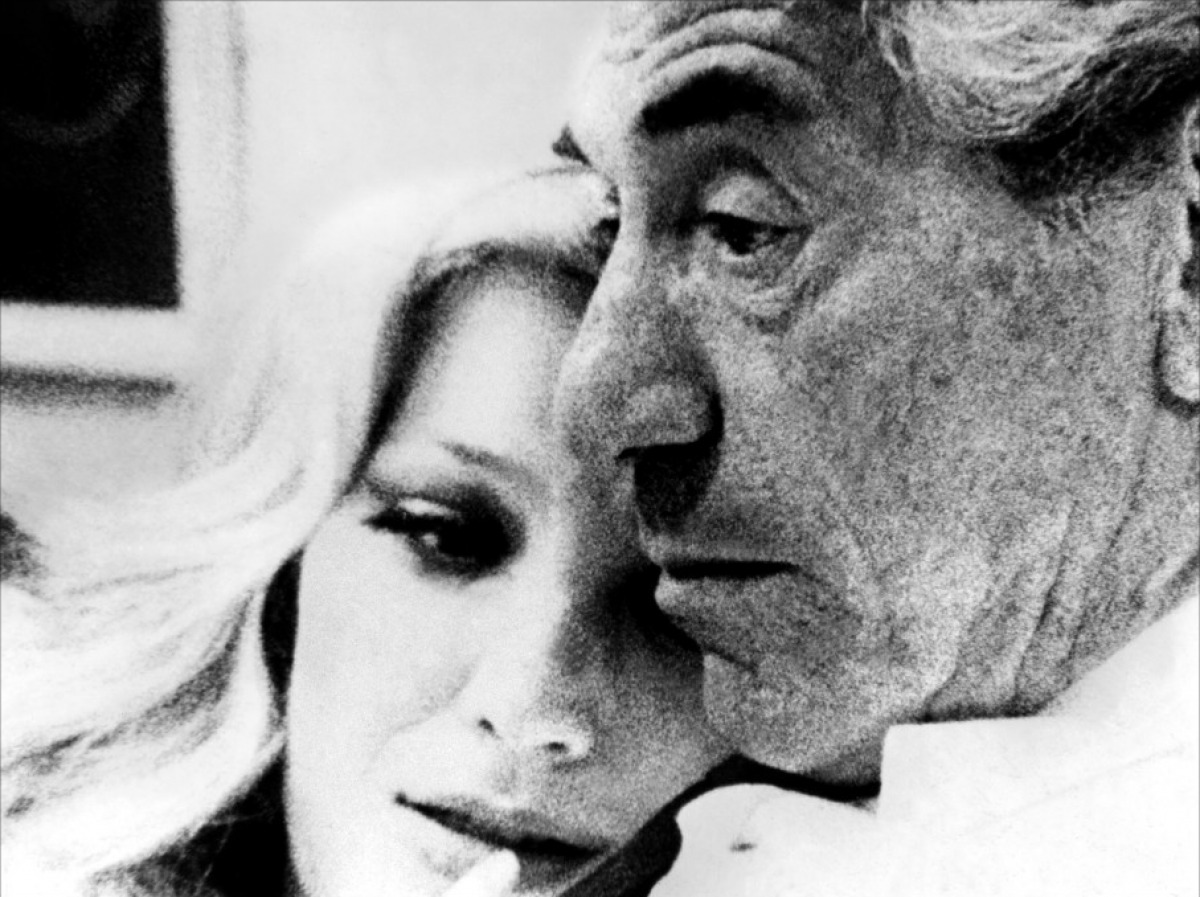

One of the New Hollywood underground’s most poetic voices was John Cassavetes. His films portrayed dissatisfaction, heartbreak, and love in ways not many filmmakers were capable of in his day. Along with a bare-bones DIY ethic, Cassavetes’ self-financed and acquaintance-cast films have stood the test of time and are lauded by many major filmmakers and actors to this day.

Financed with the money from a series of film roles made in the 1960s (one of them being Rosemary’s Baby), Faces is a drama that doubles as an exercise in cinematic form and unique performance. Shot mostly in close-ups on grainy 16mm film, Faces has a unique cinema-vérité style where details are meant to be read in the expressions and not just the performances, where the smallest distraction could lead to a gigantic misunderstanding on the part of the viewer.

The story is simple enough, a married couple’s life is shattered when the husband suddenly wants a divorce. Although mutually unhappy, the couple respectively go out that night and become embroiled in affairs that yield different results and reactions from the significant others ultimately forcing the characters to live with the decisions they have made.

Cassavetes’ knack for sudden plot twists is frequently seen in Faces. The divorce announcement, ever-shifting mood swings, suicide attempts, and situational violence quickly resorting to realistic tenderness are all present in this film and are worked into an art that could only come from the mind of Cassavetes.

While 1967’s The Graduate may have been a comment on the youth’s uncertain future in the 60s, Faces manages to transpose this same uncertainty onto the faces of the older generation who seemed to be just as dissatisfied despite their accomplishments.

6. The Wild Bunch (1969) – Sam Peckinpah

An ode to the classic Western and a heavy comment on violence, Sam Peckinpah’s most well-known film The Wild Bunch is a bloody coup-de-grâce for a bygone era. Much like John Ford’s The Searchers (1956) and Sergio Leone’s Dollars trilogy (1964-66), The Wild Bunch eventually became the norm for Western-film style while uniquely representing the archaic values of both the Old West on cinema and the studio system itself.

Peckinpah took a page from the classics in representing the aging group of outlaws attempting to stay true to their ways amid the social and technological advancements of the 20th century.

The Wild Bunch, set in the Texas-Mexico border area of 1913 contains imagery unfamiliar to most Westerns. Cars are driven, the characters fire Colt 1911 pistols instead of revolvers, and talks of World War I in Europe are mentioned. It is uneven terrain for the group of rugged thieves who simply want to continue to stick to the old way.

With carnage galore, this layered film broke records in onscreen violence. The final showdown where the Wild Bunch take on a Mexican general’s battle fort is one of the most superbly-shot action sequences of all time, mastering the art of slow motion camera usage and bullet squibs. Shocking and violent, but with a lot of heart and soul, it is no wonder why The Wild Bunch is so highly regarded almost 50 years after its release.

Not a stranger to Westerns, Peckinpah managed to create a requiem for his beloved genre while paving the way for many Westerns to come in the future decades. However, with maybe a few notable exceptions, his film was never topped and provided much ammunition for the eventual cynical explorations Westerns would later delve into.

7. Little Big Man (1970) – Arthur Penn

After the smashing success of Bonnie & Clyde in 1967 and the social protest film Alice’s Restaurant in 1969, Arthur Penn carried on the theme of American folk heroes and mythological figures with Little Big Man.

Based on a picaresque novel about a 121-year-old man named Jack Crabb, who claims to have survived the famous Battle of Little Big Horn, a massacre that left no white man alive. From the outset the credibility of the film’s narrator is called into question, but the romanticism and depth of his story captivates the audience perfectly.

Starting in 1859, Crabb’s parents are killed by the Pawnee, eventually brought up and raised among the Cheyenne, Crabb finds new identity among an indigenous people group despite his being different from them. What follows afterward is an epic chronicle of Western and Native lore, systematic violence, and adventures both high and low where Crabb (the titular “Little Big Man”) brushes shoulders with American historical figures like Wild Bill Hickok and General George Armstrong Custer.

Predating Forrest Gump by almost 25 years, Little Big Man makes comments on America’s shady history with the Native Americans as well as makes overt comments on America’s involvement in Vietnam, turning a critical eye toward the government’s strategies surrounding violence and unjust treatment of entire people groups for White Anglo-Saxon gain.

Although the film is a comedy at its core, some of the imagery in Penn’s film is heartbreaking, giving it a perfect balance of the uplifting and the tragic, making it one of the greatest satires of the New Hollywood era.

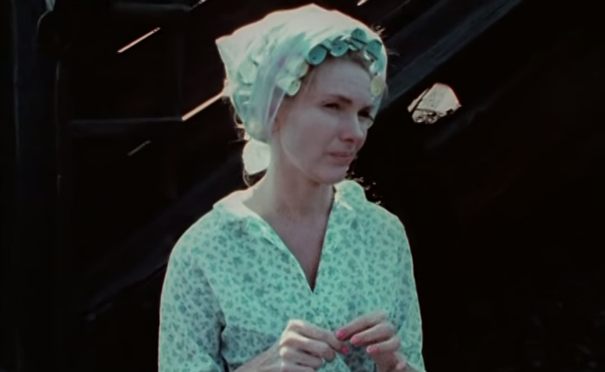

8. Wanda (1970) – Barbara Loden

One of the greatest examples of female directorial prowess, Barbara Loden’s only feature-length film Wanda is an exploration in women’s struggles and desires for independence from oppressive male-dominated society.

Starring herself in the titular role, the grainy camera captures one woman’s journey in dire times. This mostly silent character observes and takes in every pitfall, night alone, and raw deal she experiences with an almost zen-like attitude, ultimately falling in with a criminal on the run.

At times harsh, Wanda also has an unmistakable charm in its characters, especially Loden’s Wanda who balances the fast-paced world around her with quietness and slowness.

Definitely inspired by works of the auteurs like Truffaut and De Sica, Barbara Loden became one of the foremost examples of female filmmakers at the time, producing a stellar work that has become highly influential.