We all know about the directors who only make one good film or one masterwork, we enjoy listening to their brief time in the spotlight and lament at what might have been if every entry in their filmography was as critically acclaimed as their singular masterpiece. But some directors go a step further, where they only make one film, period.

Forget M Night Shyamalan and his gargantuan decline after The Sixth Sense, or John Singleton’s failure to reach the same dramatic heights he did with Boy’z n the Hood and never mind the fact that Richard Kelly has never struck gold since his spectacular debut, Donnie Darko.

While those directors gradually faded into obscurity and never achieved the same success with any of their subsequent projects, they nonetheless continued to make films and were placed behind the camera many times since. The films on this list stand as the only ever effort by their directors, the only foray into the profession that ultimately makes you wonder what might have been to an even greater extent.

For whatever reason, these directors chose to leave their career as a director with just one entry in it. Maybe they had the sense to quit while they were ahead, perhaps though their work was well received, the ordeal of directing it had been too much of a trial for the filmmaker to attempt again or maybe their film was looked upon unfavourably at the time and subsequently discouraged them from directing only for their work to be re-evaluated years later?

Regardless of the actual reason, here are ten films that still stand as the only directorial effort from their filmmakers.

10. Phase IV (Saul Bass, 1974)

Saul Bass was one of the most prolific graphic designers of the 20th Century, having worked on movie posters, title sequences and various logos. It should be considered little surprise then that his only directorial outing was full of engaging and innovative visual wonders. At the time, the film itself was heavily criticised for prioritising its effects over its story, but today it is admired as a visually inventive marvel and has attracted a significant cult following as a result.

The story centres on a group of scientists facing off against a legion of super intelligent ants in the Arizona desert. As well as being the first film to depict a geometric crop circle, in this case created by super-intelligent ants, it has influenced a number of recent science fiction filmmakers.

Phase IV is by no means a perfect movie, but it still stands as a contemplative view of humanity’s relationship with the unknown and has been recognised due to its innovative use of various pioneering visual techniques, such as rear projection effects, and geometric designs and macro close ups. At the time, however, its low box office gross and unfavourable critical reception led Bass to never direct another movie.

9. Kotch (Jack Lemon, 1971)

Jack Lemon was a legend in front of the camera, having starred in countless classics such as Some Like it Hot and The Apartment, Lemon received eight Academy Award nominations for acting, winning two for Mister Roberts and Save the Tiger. But all of this success behind the camera only equated to one effort behind it, the 1971 comedy-drama Kotch.

Adapted by John Paxton from the 1965 novel of the same name by Katharine Topkins, the film tells the story of an elderly man who runs away so as not to be put into a nursing home, and strikes up a friendship with a pregnant teenage girl.

The film partnered Lemon with his regular collaborator and best friend Walter Matthau, who despite playing a character twenty years older than his actual age, delivers a wonderfully light yet heartfelt performance, earning him an Academy Award nomination for best actor.

Despite the fact that Lemon held a passion for directing, he found the process of helming a feature film, even one with a fairly minimal scale and somewhat simplistic story as Kotch, emotionally and physically exhausting, as well as immensely time consuming. Given that both his true passion and true talent was undoubtedly in front of the camera, Lemon returned to acting soon after and did not pursue another project as a director.

8. Venom and Eternity (Isidore Isou, 1951)

If you have never heard of this 1951 film, then I can’t say I blame you. It is one of the most directly confrontational and aggressive films ever released. It is not aggressive through action, but through words as Venom and Eternity was the only film directed by Isidore Isou, a Romanian-born French poet, film critic and visual artist. He is also credited as the founder of the avant-garde movement known as Lettrism.

Venom and Eternity was Isou’s experimental and revolutionary film that upon its release was deemed revolting by many critics. It was one of the biggest talking points at the 1951, as it was a film that had not been invited, was never properly screened and went on to win a made up prize. It was only due to the barrage of requests from Isou’s followers that a screening was finally arranged.

Including a reflexive discourse on the making of a new cinema, it became a virtual Lettriste film manifesto. Attacking many film conventions by chiselling away at them throughout his film, Isou introduced the concept of “discrepancy cinema” where the sound track has little or nothing to do with the accompanying images.

The sound track of Treatise consisted of jarring and unpleasant human noises, which continued in low volume throughout the spoken dialogue. Furthermore, the celluloid on which the film was recorded was deliberately attacked with destructive techniques such as scratches and bleaching. Both were used to make Venom and Eternity a direct assault on the image and sound of film itself.

Having been impressed by the daring nature of the film, Jean Cocteau created an award to bestow on the director: the Audience Prize for Avant-Garde Film. Given the tumultuous and highly experimental nature of Venom and Eternity (which was later dubbed “the anti-film”), it was unsurprising that Isou never returned to directing.

7. Quick Change (Bill Murray, 1990)

Few actors have as much experience in both the indie and mainstream film circuits as Bill Murray, having been in big budget blockbusters such as Ghostbusters to small indie gems such as Rushmore or Lost in Translation. With all of this experience, it should not be very surprising that Murray has ventured into directing his own film, the surprising thing is that he has only done it once, and even then it was in partnership with Howard Franklin.

With Franklin writing the screenplay and Murray starring and producing, they bother undertook the role of director together. Quick Change was a unique and highly innovative crime comedy caper, in which the perfect heist has the most disastrous and convoluted getaway one could imagine.

Under his own direction, Murray turns in one of his most underrated and funniest performances. His usual sardonic and deadpan tone is put to excellent use here, defining the tone of the film as the films manic events and circumstances are underpinned by his brilliant straight-faced reaction to each event as it unfolds.

The supporting cast are also mightily impressive, with many prominent comedic actors of the era turning in some of their finest performances as well such as Geena Davis, Randy Quaid, Phil Hartman, Jason Robards and Stanley Tucci.

The film was not a major commercial success which may explain why Murray chose not to get behind the camera again, though he would work with Franklin again on The Man Who Knew Too Little and Larger than Life, but to this day Quick Change remains their best effort together by far, which may be down to the pairs directing skills.

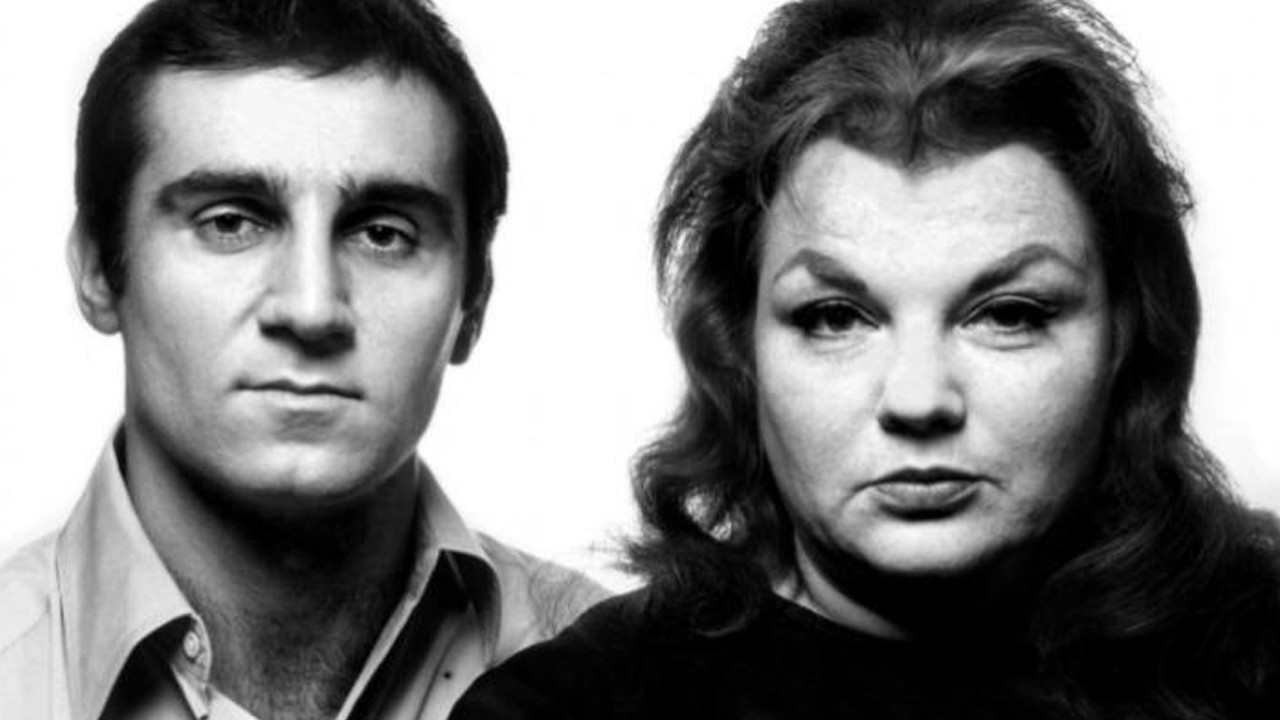

6. The Honeymoon Killers (Leonard Kastle, 1969)

If you have never heard of this 1969 crime film, then it may interest you to know that Francois Truffaut named it as his favourite American film. It was written and directed by Leonard Kastle and not only was it the writer’s only directorial effort, it was his only venture into cinema at all having worked primarily as an opera composer and librettist.

In fact the screenplay itself originated due to first time producer Warren Steibel being given $150,000 to make a film, having been convinced to do so by his friend Leon Levy. After deciding the film would be about The Lonely Hearts Killers, lovers who conned and murdered several women during the 1940. Steibel asked Kastle, his roommate, to do some research on the subject and financial limitations led Steibel to ask his friend to write the screenplay.

In fact, the exact reason for Kastle undertaking the role of director was also down to chance. Having submitted the script to the studio, Martin Scorsese was originally hired to direct the film, but was subsequently fired for working too slowly. Donald Volkman was hired as a replacement, but lasted only two weeks. Kastle then stepped in as director for the last four weeks of principal photography.

Initially marketed as an exploitation film, The Honeymoon Killers ended up underperforming in the United States and gained only a moderate gross in Britain and France. The low budget gives the film a grounded and gritty edge that compliments its underlying themes of crime and passion. Despite being a first time director, Kastle was able to craft the film with exquisite attention to detail and authenticity. He blends moments of black comedy and brutal violence together in an enduring tale of love with a body count.