Some have claimed that the 21st century has seen increased levels of isolation and depression. This has been the result of many social factors, such as the impact of social media. Accordingly, there has been a steady rise in unemployment, and a wave of global suffering that works to bring us all down.

In this way, it seems fitting that there have been a lot of films this century that deal with this collective experience of hopelessness, loss, and sadness.

These films have dealt with a plethora of issues, characters, and settings in which such negative feelings have been felt. Indeed, they have also left the audience with similarly indelible experiences, which make us think about the complexity of the human condition and the times in which we live.

20. The Edge of Heaven (2007)

“The Edge of Heaven” is a film fraught with death and fragile human relationships. Admittedly, there is not much of a story linking the disparate events of the film together. Instead, we are forced to confront the depressing relational climate that engulfs the film.

The characters all have an inner turmoil, or an apparent dissatisfaction with the state of their existence so as to enter into hasty, poorly-developed relationships. Ali (Tuncel Kurtiz) demands Yeter (Nursel Kose), a prostitute, to stay with him and only perform sexual acts on him.

The relationship is rather meaningless, essentially representing an ugly last resort for both characters. Ali’s son, Nejat (Baki Davrak), seems to be successful; he is a German literature professor. Oddly, he makes it his mission to track down Yeter’s daughter. Despite his professional success, it is clear that Nejat has a gaping void in his sense of connectedness with other people.

Meanwhile, Ayten (Nurgul Yesilcay), Yeter’s daughter, and Charlotte (Patrycia Ziolkowska) have the only functional, healthy relationship in the film. Nonetheless, they are driven apart by external forces, delivering the final death blow to any sense of redemption or contentedness.

“The Edge of Heaven” is ultimately weighed down in a sea of quiet frustration. Aside from the failed relationships, Germany and Turkey are photographed anaemically, reinforcing our sense of the deprivation of living.

19. Beyond the Hills (2012)

This Romanian film confronts the perturbing implications of total religious devotion. That is, the female characters in the film are stultified and their agency eliminated because of religious rule.

The setting, an Orthodox church in a vast space of dead grass, adds significantly to the sense of overwhelming dread and lack of self-determination. The setting is akin to something one would expect from a horror film, and it thereby helps to morph the film into something of a horror film unto itself.

The only genuinely felt relationship depicted in the film is between two orphan girls, Voichita (Cosmina Stratan) and Alina (Cristina Flutur). Their relationship is founded on a mutual dependence on one another, and also veers into the sexual realm at times. They provide each other a tangible degree of comfort in a religious climate that seems to go against everything it preaches.

It is obvious that the extreme piousness of the community dictates choice and love, thereby depriving the individuals in the film any control over their own lives. Rather than deliver soulfulness and purpose, the dogmatic command of the church brings about despair and loss, best exemplified in the horrifically violent way the church tries to cure Alina of her ills by restraining her, leading to her untimely death. Undeniably, the conclusion of the film saps all the peace from the film, if it ever had any in the first place.

18. Anomalisa (2015)

Director Charlie Kaufman is somewhat of an expert on feelings of loss, emptiness, and sadness. In “Anomalisa”, an animated film, its tone is instantly recognizable as Kaufmanian. Michael (David Thewlis) is unhappy with the way his life has been tracking, and is rather numb to his experiences.

Simultaneously, Kaufman’s directorial decision to have all characters have the same voice is both hilarious and telling. Clearly, Michael sees everyone the same way: sad, and undeserving of his attention.

“Anomalisa” is founded on an existential crisis, but it emancipates itself from this description when Michael meets and falls in love with the flawed Lisa (Jennifer Jason Leigh). Although the film begins, steeped in sad loneliness, Michael’s love for Lisa allows the film to transition to a regenerative tone.

17. One Hour Photo (2002)

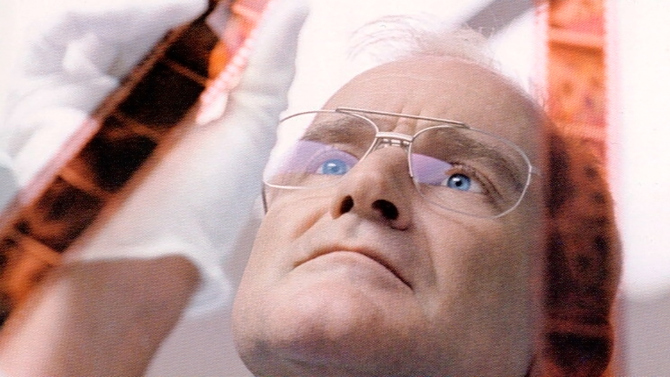

“One Hour Photo” is ostensibly a thriller, condemning its main character, Seymour Parrish (Robin Williams), for his creepily intrusive voyeurism toward an ordinary family. However, Parrish’s dysfunctional actions originate from an uglier source that allows us to sympathize with his unenviable situation.

Parrish is a diligent worker at a local convenience-like store, preparing and selling photo stock. We get the sense early on that his application to work emanates from a lack of meaning in the rest of his life, particularly in his absence of a social life. His unhealthy obsession of the Yorkin family, who repeatedly comes into the store, is patently misapplied and inappropriate.

But, we can’t help but understand this as a manifestation of his loneliness. Most notably, his anger toward Will Yorkin (Michael Vartan) for having an affair is understandably due to his utter isolation. Parrish is intent on humiliating Will because he has compromised everything that Parrish wants and will never get.

When we find out Parrish has been subjected to abuse, the sympathy we have for him only increases. Simultaneously, his pit of lonely meaninglessness is only compounded.

16. Shame (2011)

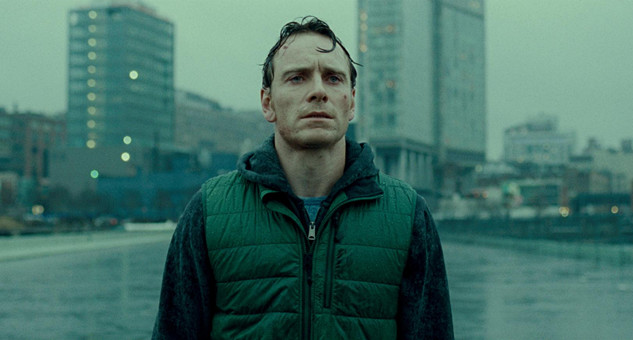

“Shame” is a slick piece of filmmaking from the emergent Steve McQueen. Brandon (Michael Fassbender) is engulfed by sexual addiction. At every opportunity, he seeks out women and attempts to bed them, at the expense of the rest of his social and personal obligations.

The world of modern New York City acts as a counterpoint to the ugliness of addiction, as McQueen frames the city as vibrant and alive. Likewise, Brandon’s sexual forays seem fun and gratifying, but really, that just masks the ugly nature of the addiction that underlies his life.

Underneath, Brandon is awash in misery and a lack of self-control. We are adequately equipped to see how the addiction has negatively affected him.

Nonetheless, Brandon’s constant neglect of his unstable sister, Sissy (Carey Mulligan), has fatal consequences, and that is when we finally realize the extent to which Brandon has been held hostage by his compulsions. Such powerlessness ends in abject emptiness.

15. Brokeback Mountain (2005)

Ang Lee’s magnum opus, “Brokeback Mountain”, is probably the most prominent film depicting the struggles of gay men. Both Ennis (Heath Ledger) and Jack (Jake Gyllenhaal) are married to women, living out the life expected of rural men. This life is a lie, as they both find connection and love with each other. The social forces of the rural setting, nonetheless, prevent them from being together.

The film is different from the average romance film, as it addresses a pervading problem in society – that men who love each other cannot always be together. In this respect, we feel greater sympathy and regret for Ennis and Jack, as we know that their case is not exceptional.

14. Mystic River (2003)

Clint Eastwood’s cinematic manifestation of Dennis Lehane’s novel, “Mystic River”, is a troubling portrait of the resonating effects of child abuse.

The film commences under a cloud of sorrow, after we realize that David (Tim Robbins) was molested as a child. This is obviously intensified once Jimmy’s daughter is murdered, and Jimmy (Sean Penn) angrily and relentlessly searches for answers. His anger becomes blinding, in so far that he believes that David was responsible for his daughter’s death.

The film ends on a more depressing note than on which it began, conveying the way in which these tainted friendships further collapse after tragedy.

13. Ida (2013)

Filmed in morbid black and white, “Ida” is a film about the limitations religious observance places on its subjects. Ida (Agata Trzebuchowska) is apparently reduced to a shell of a person because of her association with the church. The rest of the film, punctuated by slow and examining camera movement, follows Ida as she looks to her family’s past, as well as her own future.

The way in which Ida is visually presented is paramount in creating a sad, pensive atmosphere. Trzebuchowska’s expert acting, namely her innocent but worried looks, helps to reinforce the overarching tone of the film. Moreover, the film makes intelligent allusions to the horror and anguish that has undoubtedly been felt in modern Poland.

12. Inside Llewyn Davis (2013)

On the surface, and in consideration of the Coen brothers’ other films, “Inside Llewyn Davis” seems to be a comedy. It places the titular character, Llewyn (Oscar Isaac), in a number of strange and awkward situations that elicit equally bizarre responses from him. The comedy, though, acts to cut through to and highlight the real core of the film: that despite Llewyn’s obvious talent, he is ultimately a failure.

The Coen brothers smartly bleach the film of its color, opting to present us with a weathered, anaemic picture of ‘60s New York. Even though Llewyn is presented as hubristic and unlikeable, as exemplified in his exchanges with ex-girlfriend Jean (Carey Mulligan), we still see him as a sympathetic, pitiful figure. Therein lies the tragedy of a talented man consigning himself to a world of artistic invisibility.

11. Melancholia (2011)

Lars von Trier’s film is a profound cerebral and visual piece on the dangerous depths of psychological withdrawal and depression. The large-scale, meticulous imagery von Trier employs gives us a sense of Justine’s (Kirsten Dunst) internal affairs, while also conveying to us that human existence is brief and insignificant, but nonetheless fraught.

The first act of the film is defined by Justine’s impending marriage. Despite the glamour that surrounds her, her withdrawal from the event is palpable. This is facilitated by von Trier’s invasive but grandiose use of mise-en-scene and the camera.

The second act, reaching beyond Justine’s personal problems, confronts the existential crisis of a another planet hurling itself towards Earth. This is presented as all-encompassing and a moment of undefined despair for Justine and also her sister (Charlotte Gainsbourg). In particular, von Trier employs grand, overwhelming imagery of Earth’s impending doom to remind us of human finitude and helplessness in such a moment of environmental catastrophe.