The ‘70s were a tumultuous time for America, to say the least. Coming out of the idealism and liberty of the counter-culture movement that began in the mid-to-late ‘60s, which was quickly revealed to be a mess of new and old traditions.

Although the 70’s is often looked back on with some negativity, it produced a new generation of quality work from filmmakers who tapped very heavily into their generational experiences.

Some even claim that America’s “Golden Age” of film was in the 70’s, as more films were independently financed, and even Hollywood was more influenced by world cinema, which resulted in an overflow of gems that have since been hidden, obscured, or simply not watched enough.

1. Joe (1970)

Joe is certainly one of the most timely and potent films made during this counter-culture era. Just six years before winning his Best Director Oscar for his most acclaimed film, Rocky- and 14 years before the fan favourite, but non-Oscar winner, The Karate Kid- John G. Avildsen was primarily making films about losers, not winners.

This off-beat comedic drama starts with Melissa, (Susan Surandon in her feature debut) whose junkie-dealer boyfriend Frank (Patrick McDermott) is killed by her own father, Bill (Dennis Patrick), in a moment of fury after she is hospitalised for an OD.

Though Bill is shocked by his own actions, his outlook changes when, immediately after the murder, he meets Joe (Peter Boyle), an uber-conservative who despises all that comes from these new traditions.

Joe hates the younger generation and their liberal ideas so much that he prefers a conservative hippie-murderer over a peaceful drug-user any day. Joe also endlessly and vocally complains about black people, welfare, and hippie culture, and embodies the opposition that the shifting cultural landscape was up against at the time.

Although the film has a deeply anti-violent message, its overriding themes are even more cynical than Joe’s moral viewpoints in some ways- it very critically observes the aimlessness and lack of certainty of the counter-culture, while simultaneously criticising the mindless and complacent subservience of the older culture.

However, despite the negative attitude, Joe is a riotous film, mostly brilliant and hilarious because of its title character whose constant misanthropic tirades are an alarming hoot to watch, especially as they escalate to a violent climax- the type of comedy that initially shocks, but goes deep. Supported by a fantastic soundtrack and a steady finger on the pulse of America at the time, Joe is a film to love, starring a character you’ll love to hate.

2. Trash (1970)

Another film to take a harsh look at the counter-culture 70’s crowd was this no-budget effort from the Warhol Factory, which was written, directed, shot, and edited by Paul Morrissey (though it’s often erroneously referred to as an Andy Warhol film). The film follows Joe (Joe Dallesandro) through this series of unimportant vignettes.

Joe is a young man with good hair who’s always strung-out, and always keen for his next hit. His spacey and careless character is in constant conflict with his stressed and exasperated room-mate Holly (Holly Woodlawn), with whom he has a very vague relationship.

In this graphic and down-to-earth film, we see Joe in a few awkward situations- he fails to get hard for his mistress; he shoots heroin for the spectacle of a newly-wed couple after they find him breaking into their house; and he tries to scam the welfare department.

Although Morrissey describes it as a comedy, Trash is a rather dark film that shows how shallow and hollow life could be for unemployed and squalid hippie folks, who sometimes had to make a living literally selling garbage.

Trash is an incredibly rough film with very bizarre and experimental editing, camerawork, and dialogue- but it all cements its realist style that is as grounded as it is satirical. If you’re keen for a film done with limited resources, but with a wealth of kooky and culturally illuminating characters, Trash is a superb film to really get an idea of what it was like back then- and it’s not as pretty as Hollywood would have us believe.

3. Husbands (1970)

After his hits Shadows (1959) and Faces (1968), and before A Woman Under the Influence (1974) and The Killing of Chinese Bookie (1976), Cassavetes made his most vivisectional works about male friendship.

Shot in the same extremely raw and seemingly spontaneous style that he employed in his first two films, and cast with the usual Cassavetes gang, Husbands is made up of Gus (Cassavetes himself), Harry (Ben Gazzara), and Archie (Peter Falk) as they go through a collective mid-life crisis following the sudden death of one of their friends.

Their efforts to shake off this grief include the usual gallivanting and self-pity- drinking themselves into a stupor and even travelling to London and attempting to cheat on their wives back home. But all of the potential joy they experience in this film is tinged with a great degree the mens’ own childishness, selfishness, and sadness.

The three leads really make the film. Their spontaneous and very naturalistic performances give it a lot of life, even though the story calls for a very flaccid kind of life. Despite its loose structure, Husbands may be Cassavetes’ sharpest directorial effort; the one that stabs the most precisely at male friendship and all that it entails.

4. Hi, Mom! (1970)

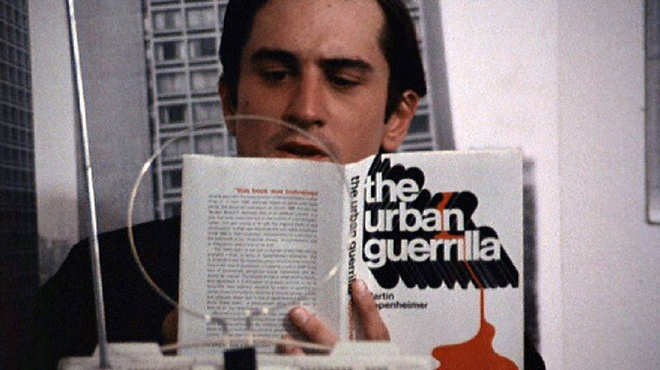

An early feature from both actor Robert De Niro and director Brian De Palma, this sequel to their even earlier film Greetings (1968) was an absolute shock to the system, and its intense narrative still resonates viscerally among viewers to this day.

Jon Rubin (De Niro) moves into a shady new apartment solely for the purpose of voyeuristically filming the tenants in the building across the road. Rubin then sells the tapes to pornographers who market it as a new kind of fetish.

The movie starts off as a sly, satirical comedy, but there is a feeling early on that this film may not be quite as it seems. That feeling is villified halfway through when it diverts suddenly from a Rear Window-as-light-comedy kind of film into something totally different, with the Be Black Baby sequence of the film.

This segment documents a stage-play that is filmed in total cinema verite style, a la Blair Witch Project, though even more harrowing. In this sequence the entirely white and middle-to-upper class get a dose of a harsh reality in the most extreme theatrical manner possible- which is pretty frightening to watch as it resembles quite an authentic-looking snuff film. Though, this sequence also acts as a satirical hyperbole of the ludicrous lengths both theatre groups and social activists go to in order to make their points.

This sequence may feel more horrifying on its own, but it is sandwiched by a (conventionally filmed) fairly comedic exploration of celebrity culture, which certainly paints the Be Black Baby sequence a different colour.

Hi, Mom! was a totally audacious film for its time, in both its obtuse narrative form and its confrontationally controversial subject matters, and it continues to be with each passing Western social fad, which at their roots, never really seem to invoke much change. Which is perhaps what keeps this film so fresh.

5. The Last Movie (1971)

What is there that can be said about Dennis Hopper’s sophomore directorial film? Reminiscent of the tripping-out sequence towards the end of Easy Rider (1969)- though keep in mind, that feeling lasts for the entire film- The Last Movie is an unfathomable oddity that was crafted after the success of Easy Rider.

Universal had given Hopper full creative control over this relatively low-budget film and, boy, were they shocked when they saw the final edit (which they had no control over). The wildness of the final cut forced Universal to give it a very limited release, suffocating its chances of becoming a cult hit like Easy Rider.

Hopper’s director career was stunted at this point (until he returned in 1980 with the conventional, yet excellent Out of the Blue), though it’s understandable that Universal got cold feet after seeing the movie.

The Last Movie could’ve indeed been the last movie ever made- it is so youthfully and energetically filled with fourth-wall-breaking references to its own medium, many of which without rhyme or reason – just when you think you’ve got the film figured, it diverts to something else.

The story at its core makes sense enough; Hopper plays a unit wrangler named Kansas who has recently quit a violent cowboy film production in Peru, though as he sticks around in the country and goes sight-seeing, the film production turns into a ritual for the natives to better understand fake violence- which turns out to be more real than the film they were making.

It’s hard to get a grip on this story as the film becomes more and more obtuse, even (especially) when it appears to settle on a narrative about Kansas ditching his Peruvian girlfriend for another visiting American woman, though soon returns from this digression back into movie-making madness.

The Last Movie is an astonishing achievement in North American surrealism and watching it today really makes you wonder how it ever got made at all- but that’s the ‘70s for you.

6. Vanishing Point (1971)

This existential car-chase action-thriller needs to make a comeback. Perhaps a remake of this cult favourite may be on the way (though it already had a made-for-TV special in 1997 starring Viggo Mortensen), but it’s unlikely any other film that has or ever will be made can really be quite like Vanishing Point.

With little back-story and even less character development, we witness delivery-man Kowalski (Barry Newman) and his 1970 Dodge Challenger (who essentially make up one complete character) on an attemot to drive from Colorado to San Francisco within just 15 hours, so he can make some fine dough on a bet.

As Kowalski speeds his way across America’s Southwest, he encounters the highway patrol, cops, gay hitchhikers, a naked woman on a bike, a snake catcher, and even more cops as it dawns on him (and on the audience) that Kowalski is getting the job done whether he wins the bet or not.

His real reason for this odyssey is left elusive, though even that seems to perfectly tap into the uncertainty of the era that left people from both old and new generations wondering what was happening in their countries, in other countries, and what they could do to feel existentially validated.

7. Heavy Traffic (1973)

If it weren’t for Ralph Bakshi, there is a chance we wouldn’t have South Park, Family Guy, any cartoons on Adult Swim, and maybe even The Simpsons and Futurama. Bakshi paved the way for adult animated comedy, combining the outrageous and outlandish antics of the adult underground short animated films with the feature length presentation of the more mainstream Disney films.

After bringing to America the first X-rated animated film with Fritz the Cat (1972), Bakshi began work on his magnum opus- which proved just how socially conscious and surprisingly poignant his work can be, alongside, of course all the crude humour and anthropomorphic sex and drug use.

In Heavy Traffic, we follow young 22 year old virgin and cartoonist Michael Corleone as he escapes the domestic dysfunctions at home between his Italian father and Jewish mother, to hang out on the streets with his chums or his new (and very street-wise) girlfriend, trying to get one of his comic book ideas sold (despite it being hilariously sacrilegious). It turns out to be even less safe out there than it is back home, and Michael gets himself into some unforeseen trouble.

Heavy Traffic is quite likely the best cartoon film of the ‘70s; that is if you want to call it a cartoon – the animated characters are often situated in front of real-life backdrops, or sometimes even interacting with real-life people, and as we glimpse intermittently throughout the film, Michael Corleone is indeed a real, live-action person living in a non-cartoon world.

This results in an intoxicating mix of animation and filmed footage that blends seamlessly, often in very creative and clever ways. The trailer does a good job at succinctly describing this groovy landmark of a film: “It’s animated, but it’s not a cartoon. It’s funny, but it’s not a comedy. It’s real, it’s unreal. It’s Heavy.”