The world of Japanese animation often tends to be really and quite deliciously weird. Some angels lay eggs, while the others smoke. Cute little girls take people to hell. Ghosts live and contemplate in their shells. Paprika has a flavor of dreams and nightmares. Kittens are the main ingredients of a surreal soup. And so on…

On the other hand, there are creators who wholeheartedly embrace “normalcy”, so once in a while we get a ridiculously gorgeous melodrama in which rain drops flow like tears or a humanist sci-fi dramedy starring astro-garbage collectors.

So, wheather you prefer former or latter, fall somewhere in between or don’t know how and where to start, you might find something to your liking amongst the lesser-known anime of the last century.

1. The Phantom Ship (Noburō Ōfuji, 1956)

Noburō Ōfuji is considered one of the most significant Japanese animators of the 20th century’s first half. During the most of his career, he was utilizing the technique of shadow puppetry popularized by Lotte Reiniger, so her only feature film The Adventures of Prince Achmed served as the main source of inspiration for Yūreisen.

This miniature masterpiece begins with live-action footage of the author’s deft hands cutting out the colored cellophane in the form of waves. After the tempest in the introduction, the camera slides over the map of East Asia and stops at the Yellow Sea above which the mysterious fog rises and resurrects the pirate ship crew. With a cannonball, they interrupt the celebration over at the lavish Chinese ship, turning the joyous occasion into a massacre. But, what goes around, comes around…

The story which is reminiscent of some ancient legend is told via the kaleidoscopic images draped in the silky tapestries of sounds. Ōfuji goes one step further from his “teacher” and experiments with the classic cel animation, making the characters’ movements even more elegant. Permeated by the haunting music, his hypnotic vortex of colors, lines and vivacious shapes fascinates even today.

2. Panda and the Magic Serpent (Taiji Yabushita & Kazuhiko Okabe, 1958)

Panda and the Magic Serpent (Hakujaden) is the first feature-length color anime and Toei’s attempt at jumping into Disney’s bandwagon. At the Venice Film Festival in 1959. it received honors, but a couple of years later, the American audience’s reception was cold.

An old, horror-ish Chinese legend Madame White Snake is adapted for the youngest audience as a romantic fairy tale of Xu-Xian and Bai-Niang whose love is interrupted by the Buddhist priest Fa-Hai. (Back in the day, this was supposed to be an act of reconciliation between Japan and China.)

The artwork and the score, both praiseworthy, clearly reflect the whole team’s efforts to pay due respects to their neighbors’ folklore. All the characters are voiced by only two seiyūs, whereby the budgetary restrictions are most obvious in the lip-sync department.

Notwithstanding its flaws, Hakujaden is, by Japanese standards, an atypical fantasy, given that its style is more akin to the “Russian school” or Max Fleischer toons. What’s also interesting about it is the fact that one of the animators was none other than the 17-yo Rintarō (Neo Tokyo, Metropolis).

3. Magic Boy (Akira Daikubara & Taiji Yabushita, 1959)

Inspired by a legendary ninja as fast and agile as a monkey, Magic Boy (Shōnen Sarutobi Sasuke) bears a historical significance, given that it is the first anime film to be released theatrically in the USA, prior to the previous entry on this list.

A simple tale follows the growing up of a courageous boy, Sasuke, and his struggle to stop a demon princess, Yasha, from founding a reign of terror after being released from the wizard’s curse. (The viewers who cried over the death of Bambi’s mother have to know that Yasha – in the form of a salamander – gets her powers back by devouring a doe who tries to save her fawn.)

Magic Boy is a neat fantasy-adventure which seems like an Asian parable by the way of a darkly intoned Disney cartoon. A few instances of violence are not graphical, yet the bad guys die in dozens and the depiction of the witch’s death is a bit creepy (not to mention the brute force of a final showdown which precedes it).

The character design is pretty diverse – Yasha looks like a specter from ukiyo-e, whereas her subjects remind of Ub Iwerks’s and Max Fleischer’s works. The good guys have distinctively Asian features rarely seen in the contemporary anime. But, the oscillating quality of both animation and Daikubara & Yabushita’s direction can be distracting for some viewers.

4. Arabian Nights: The Adventures of Sinbad (Taiji Yabushita & Yoshio Kuroda, 1962)

Co-written by the famous Osamu Tezuka and the novelist, psychiatrist and ist Morio Kita, Arabian Nights: The Adventures of Sinbad (Arabian naito: Shindobaddo no Bōken) is one of the earliest adaptations of the stories about the fictitious seafarer.

From the streets of Baghdad to a mysterious treasure island, it focuses on the mishaps of still young Sinbad and his best friend Ali, showing a deep respect for the Islamic customs and culture. These two dreamers stow away on a transport ship and go on a risky voyage in the waters of Middle East. They win over the captain’s trust and are later joined by a brave sultan’s daughter, Samir…

Although it’s intended for children (including the inner ones), this tame and modest fantasy is somewhat bleaker than its contemporaries from Disney production. A breath of melancholy is felt not only in the ballad sung by Sinbad at the helm, but in the cheerful songs of sailors as well.

The lush, evocative orchestrations which frequently reflect the characters’ mental and emotional state, resonate with the artistic, peculiar pictures in the vein of rotoscoped Russian classics. Without losing its specific charm, the animation has aged gracefully.

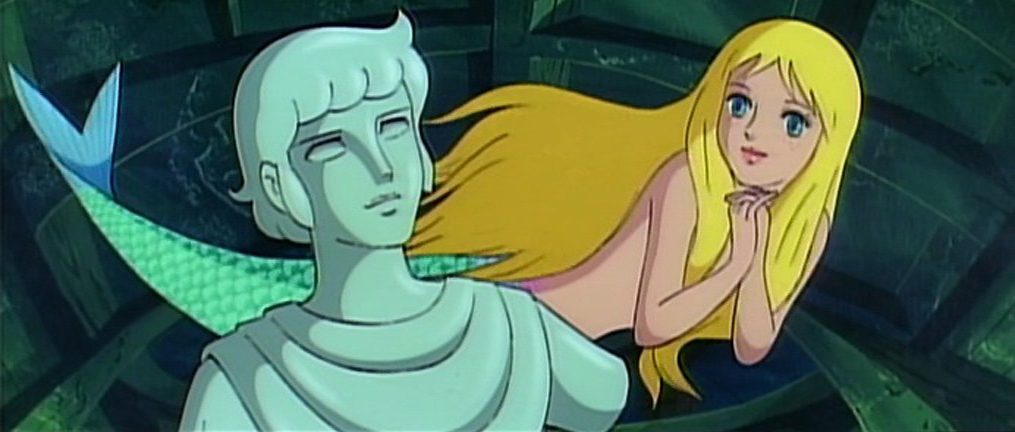

5. Hans Christian Andersen’s The Little Mermaid (Tomoharu Katsumata, 1975)

Life is not always beautiful, especially when our sacrifice is for nothing – this messages from the H.C. Andersen’s fairy tale is not lost in Katsumata’s adaptation. Created fourteen years before the most famous big screen rendition, it remains quite faithful to the original story and its ending.

In spite of introducing new elements, such as the friendly sea creatures (dolphin Fritz and whale Duke), Anderusen Dōwa Ningyo Hime is superior in content to its Disneyfied cousin. However, time hasn’t been very kind to the animation (the first to be directed by a Japanese woman), minus a few impressive scenes and the imaginative design of the colorful undersea world.

Worth mentioning are the hippy interiors of Triton’s palace and the devilfish/vampire-like features of a (handsome) witch, as well as the experimentation with live-action/documentary footage of the prologue and epilogue shot in Denmark.

Given that Katsumata doesn’t shy away from showing a few drops of blood and the tragic heroine’s bare breasts, his bittersweet anime is not suitable for the youngest kids. Everyone else (not easily turned away by outdated visuals) should give it a try.

6. The Sea Prince and the Fire Child (Masami Hata, 1981)

Another underwater fantasy brings the tale of mythical proportions which seems like H.C. Andersen adapted Romeo and Juliet and travelled to our time to collaborate with some Japanese director – in this case, Masami Hata of Ringing Bell (Chirin no Suzu) fame.

Similar in tone to the aforementioned tragic fable, The Sea Prince and the Fire Child (Sirius no Densetsu, literally Legend of Sirius) revolves around the impossible romance between Prince Sirius of Water and Princess Malta of Fire – the descendants of the estranged divine siblings Oceanus and Hyperia.

Certainly the best Hata’s feature to date, this gentle, gloomy, touching and enchanting fairy tale is a delightful treat for the whole family, albeit an unorthodox one (and Hyperia’s cleavage), and a valuable relic of the past. Its magic stems from the dense interweaving of the soaring orchestral pieces with the simple, yet fluid and uniquely stylized imagery of raging tempests and swarms of fiery fairies, inter alia.

The inclusion of the original, more detailed illustrations a la picture book during the credits doesn’t take away from the beauty of the anime – on the contrary, it is like a cherry on the top of a cake.