Vittorio De Sica was the great protector of Italian neorealism. His work was far from the philosophical musings of Rossellini and the operatic dramas of Visconti; his works had a genuine empathy for the poorest in society, and could depict their lives with a sense of tragedy and simplicity that best suited his period. Of course, his style was vastly imitated.

1. Mouchette (Robert Bresson, 1967)

Bresson was famous for his sparse, rural, and minimalistic filmmaking. He used to dry the frame as much he possibly could, eliminating the unnecessary elements to get to the heart of the philosophical themes and pushing his mostly non-professional actors to their limits.

Mouchette, the protagonist, is the daughter of an alcoholic father and a constantly ill and weak mother. She is, according to her director, the embodiment of human misery, as her crying offers an escape into the Catholic symbolism, the universal value of suffering and the wretchedness of the world that tortures the weak and the poor, as they, in their suffering, have to find their dignity, but eventually are abandoned to their pain.

The neorealist movement always had an undertone that went beyond the social realism, the cinema veritè style of the cinematography, the simple style, and reach a level of a fairy tale depiction of childhood as the ultimate elevation of innocence and genuine wonder in a world that is left with no wonder, but copious amounts of dread.

The escalation of the events in “Mouchette” ends with a tragic final scene worthy of a Sophocles tragedy, but shot with the essentiality of a documentary. Bresson, just like De Sica, had an extraordinary ability to situate metaphors within the social and existential landscape of the most disadvantaged elements of society. Their work has the depth and the grandiosity of the great 19th century novels.

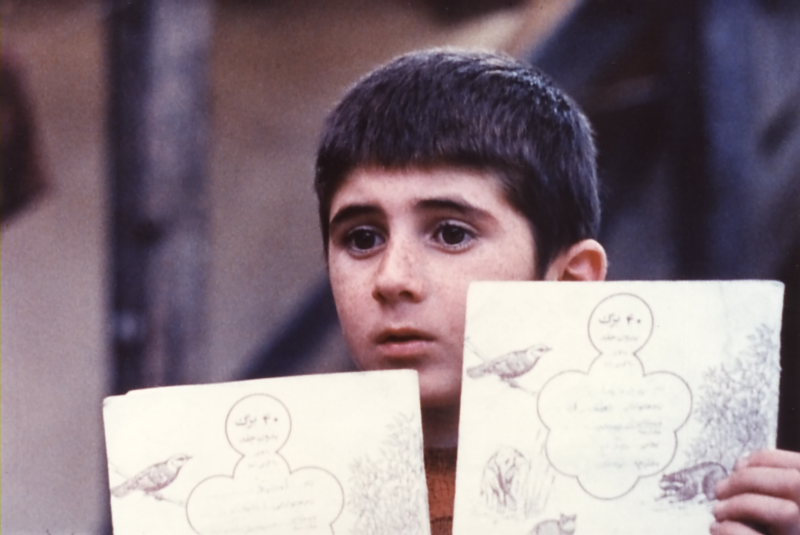

2. Where is the Friend’s Home? (Abbas Kiarostami, 1987)

Unlike De Sica and the other great neorealist filmmakers, Kiarostami invented a naturalism that abandoned every trace of staged action and relied on the manifestation of the real through the movie camera, adding a tenderness and avant-garde sensibility united with the extremely poetic rhythm and the influence of Persian mysticism, which put himself not only in the realist tradition but also at the forefront of the new experimental tendencies, such as slow cinema and others.

Another element that draws this Kiarostami work closer to the work of De Sica is the element of the quest; the kid who has to go on a journey, no matter how small or how apparently irrelevant the task is, has to do it as he exercises the common human characteristics of dignity and responsibility that make even the poorest rich in spirit.

Kiarostami shoots the landscape with a sensibility that is closer to home video than to the great political statements of social cinema; the atmosphere is gloomy and sad, far from any celebration of the land, and closer to a dark phantasy land, an archetypal fairy tale set in a contemporary context with a gentle treatment that does not avoid universal themes, but explores them through the smallness of individual experience.

3. Aniki Bobò (Manoel de Oliveira, 1942)

Despite the fact that Italian neorealism is held to a standard so high that it almost single-handedly helped define the concept of the European “art film”, the movement was anticipated by a series of films in the late 30s and the early 40s that set the stage for Visconti, De Sica, Rossellini, and the other Italian masters. Some of these films came from India, some from China, some from Japan, and there is “Aniki Bobò” by the legendary director Manoel de Oliveira.

Again, the strata of society that is depicted in the film is the children of a village in Portugal, a somber village near the sea, with houses made of stone and fishing boats placidly resting on the ocean. The film is a story of children who fight for the love of a young girl. Again, the theme of childhood is central, as the introduction of an element of poetic innocence into a depiction of society that strives for realism.

Despite these parallels, since Portugal was relatively untouched by World War II, it lacks the element of realist desperation that is associated with part of the neorealist canon. In this film, the children have some spring in their step, the atmosphere is sunny, just like the blonde hair of the young girl they are chasing. There is also singing, and there is a deadpan and serene irony in the staging of every sequence, with a touch of melancholia that is comparable to Jean Vigo’s “L’Atalante”.

The film has some traces of the city symphony genre in which de Oliveira made his debut in 1931, but “Aniki Bobò” was the first major work from the director, who then went on to make films until 2012, a longevity that is unheard of in cinema. He crossed all the major cinematic movements, and this is his best neorealist work.

4. Sidewalk Stories (Charles Lane, 1989)

“She’s Gotta Have It” by Spike Lee started the African-American cinematic new wave in 1986, and three years later Charles Lane directed “Sidewalk Stories”, a low budget film about a street artist who has to take care of a child after a tragic event.

The child is once again present as a thematic connection, and the film, inspired by cultural and critical theories of cinema of the 70s, decides to emulate and redefine a classic of Hollywood comedy, Charlie Chaplin’s “The Kid”, through a cinema veritè and the addition of the context of poor African Americans in a post-segregation society.

Along with the comparisons to silent cinema, the film also has the melancholic jazzy tone of a John Cassavetes film, and the simple realism of Kiarostami. The film is minimalistic and yet has a spacey atmosphere of a fairy tale that is close to the Golden Age of Hollywood.

Postmodernist neorealism might be an accurate definition for the film, as the shots of the imposing New York city landscape contrasts with the misery of the poor, the microcosm and the macrocosm.

In the end, the comedy starts to slowly die, as the American Dream archetype dissolves more and more, and we realize that the times of Frank Capra, of Chaplin, and of decorative American cinema, are over. “Sidewalk Stories” is a neorealist film that not only shows the culture and society, but deconstructs them as well.

5. Stray Dogs (Tsai Ming Liang, 2013)

Tsai Ming Liang’s last film is apocalyptic realism. The film follows an extremely poor family in a series of unbroken shots that achieve a level of brutality and nihilism in the depiction of humanity that is almost unmatched.

In the film, the human figure gets downgraded to the level of an animal; even the capacity to speak is reduced, as the expression on the faces are deformed by sorrow, pain, and hunger. Even the children, usually an escape from dread, are reduced to tears and laments as the only valid forms of expression.

The two most impressive shots of the film are the dramatic rain sequence, when a torrential rain, with an incredibly noisy soundscape, invades the screen like a neorealist William Turner painting infused with acid urban poison. The other incredible sequence is the ending, which is amazing in its radicalness. Ming Liang goes right over De Sica and Rossellini, right through Antonioni and modern cinema, to reach a new condition, a post-human neorealist cinema.

No film, perhaps only Bela Tarr’s “The Turin Horse”, has the feeling of the reaching the extreme point of the poetics of a filmmaker like “Stray Dogs”. The city is not only the landscape where the human experiences are played out in their smallness and their misery – now the city is where the human experience disappears, and becomes one with the concrete walls and the dirty streets, the acid rain and the washed out paint on the walls of the streets.