One of the most controversial American directors in the history of cinema, Brian Russell De Palma also remains one of the most divisive and poorly understood. Part of the influential New Hollywood wave of filmmakers, De Palma has been perfecting polemical and exhilarating cinema since the 1960s.

To his critics he’s been labelled a misogynistic chauvinist, a sell-out, and a poker-faced plagiarist of Hitchcock. To his admirers and to the critical establishment outside of America he’s regarded as an auteur, an avant-gardist, an au fait satirist, a passionate independent iconoclast and an articulate intellectual.

In a career now spanning close to 50 years De Palma has proven to be an architect of intensely personal and analytical films, awash in stylistic flourishes, and dazzling technical strut.

A quick glance at his diverse and pervasive filmography reveals comedies like Hi Mom! (1970), and Get to Know Your Rabbit (1972), midnight rock opera excesses like Phantom of the Paradise (1974), prestige horror like Carrie (1976), psychological suspense thrillers like Sisters (1973), Dressed to Kill (1980), Blow Out (1981), Body Double (1984), and Femme Fatale (2002) along with celebrated crime pictures like Scarface (1983), The Untouchables (1987), and Carlito’s Way (1993) and action-driven blockbusters like Mission: Impossible (1996).

While De Palma’s outstanding oeuvre truly does speak for itself the following list will detail several more unshakable reasons why this is a director that demands your esteem and applause.

10. Not only does De Palma ascribe to auteur theory, he validates it

“De Palma was actually the first American auteur of the New Hollywood to emerge, but the last to come to prominence… He is also the most gleefully, perversely derivative of them all, and perhaps for this reason the most in tune with the times. De Palma may be the only one of these auteurs—Altman, Coppola, Scorsese, Spielberg—from whom we might still hope for miracles…”

– Jake Horsley, ‘The Blood Poets’

Because of his persistence, tenacity and longevity De Palma has carefully amassed a body of work that is introspective, recalcitrant, and verifiably stylish. The fire and the perceptivity of his films guarantees that any deliberation of his works moves beyond deliberation of cinema and into a wider discourse on the stirrings of human nature, and the zeitgeist in which it was created.

De Palma fearlessly examines and reexamines his obsessions with such determination and with an aversion to abandon his principles. Always and forever De Palma holds to a dicey set of ideas, enduring evolving sensitivity and insight.

Films like Carrie (1976), Dressed to Kill (1980) and Blow Out (1981) were originally released to moral outrage and cries of misogynistic objection but over the years it’s easier to dismiss and scrutinize such claims due to audiences becoming progressively more sophisticated.

People can draw a line from what antiheroes and morally questionable characters represent and what the director’s objectives are. In the same way that Jean-Luc Godard, Alfred Hitchcock, and Stanley Kubrick outgrew their classifications and their circumscribed labels, so too has De Palma his.

9. De Palma is the master of many genres

“De Palma deserves more honor as a director. Consider these titles: Sisters, Blow Out, The Fury, Dressed to Kill, Carrie, Scarface, Wise Guys, Casualties of War, Carlito’s Way, Mission: Impossible. Yes, there are a few failures along the way (Snake Eyes, Mission to Mars, The Bonfire of the Vanities), but look at the range here, and reflect that these movies contain treasure for those who admire the craft as well as the story, who sense the glee with which De Palma manipulates images and characters for the simple joy of being good at it. It’s not just that he sometimes works in the style of Hitchcock, but that he has the nerve to.”

– Roger Ebert

While it’s true that De Palma’s lengthy filmography zigzags enthusiastically from genre to genre, it’s also nameable and unique that he’s gutsy when it comes to interchanging arrangements from one genre to another, transcending category as he goes.

To wit: The Untouchables is a cop film in Western garb and Oscar bait accoutrements; Mission: Impossible is an espionage thriller with Shakespearean tragedy frills; The Phantom of the Paradise is a rock opera with comedic froufrou and horror movie fandangle; Carrie and Dressed to Kill may both fall under horror taxonomy but that really does nothing to elucidate the pliable and multiform content.

De Palma’s films regularly result in film critics and theorists at odds for decades attempting to label and classified his weighty and varied works.

8. De Palma takes great risks in nearly all of his projects

“Critics—no maybe I should call them ‘reviewers’ instead of critics—are looking for the latest thing rather than the truest thing.”

— Armond White, discussing the critical abandonment of Brian De Palma

At many times in his career De Palma has been at the center of controversy. The already discussed cries of misogyny in films like Carrie, Dressed to Kill, and Body Double, his orgiastic glorifications of violence in films like Scarface and The Untouchables, to his harsh anti-American polemic in challenging war films like Casualties of War and Redacted.

In her best-selling book “The Devil’s Candy”, Julie Salamon details much of De Palma’s digressions and ventilations in dealing with antagonistic critics and special interest groups, writing; “At first De Palma was startled by the attacks, and then invigorated by them. He willingly, sometimes gleefully, went head to head with journalists eager to denounce him for the violence and violent sexuality in his movies.

People were almost always thrown off guard when they met the well-spoken graduate of a Quaker school in Philadelphia, Columbia University, and Sarah Lawrence. Articulate and convincing, De Palma could defend himself very well indeed.”

While De Palma wouldn’t always have box office success, with very few exceptions so many of his films were and are made on his own terms, and the years have been kind to his legacy, his risks reaping substantial and long-lasting rewards.

7. De Palma introduced and popularized numerous now iconic actors

It might be a minor detail in De Palma’s progression but he did give breaks to a lot of actors that would skyrocket to fame––his early comedies were Robert De Niro’s first films, Carrie made Sissy Spacek a sensation, and John Travolta was just a TV actor before appearing alongside Spacek. De Palma also helped some stars mount significant comebacks from relative obscurity like Al Pacino’s titular role in Scarface and Sean Connery’s Oscar-winning reinvention in The Untouchables.

Similarly, De Palma introduced Martin Scorsese to screenwriter Paul Schrader, suggesting that Marty and not himself, would be the right director for his ambitious little script called “Taxidriver”. And prior to that it was De Palma who introduced Marty to De Niro, who promptly cast him in Mean Streets and from there, well, you know the rest.

De Palma’s characters, the phrases they utter (“Say hello to my little friend”, “They’re all gonna laugh at you”, “Brings a knife to a gunfight”) and the ideas they represent have been eagerly absorbed into popular culture’s vocabulary.

6. De Palma has never been afraid to make confrontational and unsafe cinema

“I am constantly standing outside and making people aware that they are always watching a film… At the same time, you are deeply and emotionally involved in it.”

– Brian De Palma

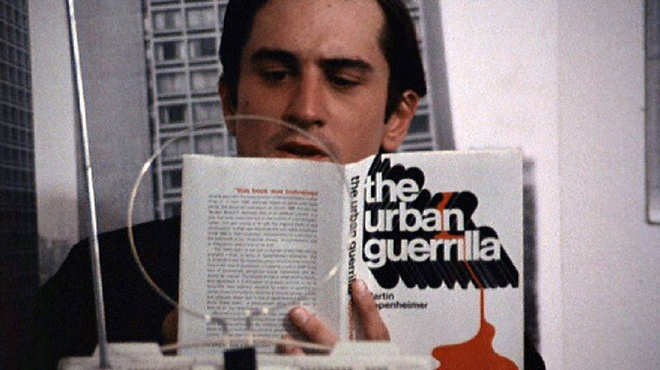

In the early days of his career De Palma was very much a politically motivated filmmaker with a Godard-like obsession for radical narrative cinema. His films of the late 60s like Greetings and Hi Mom! Confronted an image-manufacturing culture that crassly objectified women, redefined racial unrest, and the Vietnam War.

This Brechtian alienation and adversarial satire would be revisited in Bonfire of the Vanities while the more poignant and personal anti-war and arguably anti-American affectivity would also infuse Casualties of War––which Pauline Kael described as leaving her “simultaneously elated and wiped out,” in her staggering, filibuster-like eight-page review in The New Yorker––to his late period Iraq war polemic, Redacted.

The latter, Redacted, is a scathing indictment of U.S. soldiers’ brutalization of an Iraqi family under their occupation, terrified audiences with some of its shocking imagery and a montage sequence which De Palma himself was outraged about when Magnolia executives had it drastically cut. “I find it remarkable. ‘Redacted’ got redacted. I mean, how ironic,” De Palma remarked repeatedly during junkets promoting the film. And Venice still gave him the Silver Lion for his fearless direction.