Sometimes the point of view of an outsider can illuminate aspects of a culture that those within it cannot see. The United States is a vast and complex land full of diverse cultures and geography with enough subject matter for hundreds of movies.

The themes and styles of the films on this list are diverse. Billy Wilder, a German immigrant, made brilliant movies on social morays in post-war America. Many foreign filmmakers are enamored with the rich landscapes of the West, exemplified by Zabriskie Point and Paris, Texas. American literature also informs many of these films. A common theme running through nearly all of these movies lies a sense of hope juxtaposed with a desperate loneliness.

15. The Big Heat (Fritz Lang, 1952)

One of the gritty film noirs Fritz Lang made for Columbia Pictures, The Big Heat tells a stark story of urban corruption. Glenn Ford stars as a homicide detective who gets caught up in a crime involving cover ups within his own department. The no nonsense dialogue adds to the pulpy style. There are even shades of DC Batman comics with its themes of a city under the control of a brutal crime syndicate.

Ford’s perfect as the one good cop, an example of stoicism in the face of constant intimidation. A young Lee Marvin ratchets up the action as a loathsome hood capable of exploding into violence at any moment. At one point he throws hot coffee at the face of a woman, echoing James Cagney’s grapefruit smash to the face in A Public Enemy.

Lang’s taut directing style heavily influenced crime movies to come, an unsentimental depiction of violence foreshadowing the films of Peckinpah and Scorsese. The Big Heat works as a case study of the connections between German Expressionism and American Film Noir.

14. The Ice Storm (Ang Lee, 1997)

American directors from Generation X love to revisit the 1970s. Dazed and Confused and Boogie Nights revel in such nostalgia. Ang Lee’s adaptation of Rick Moody’s novel The Ice Storm goes against the grain, dissecting the dismal soul of the decade with the precision of a brain surgeon.

Set in the waspy suburbia during Thanksgiving weekend of 1973, the film oozes with unease and melancholy. Parents and children deal with ennui, alienation, and sexuality.

The story centers on two families who become intertwined in more ways than one. Kevin Kline and Sigourney Weaver are having a perfunctory extramarital affair. Meanwhile Kline’s wife (Joan Allen) looks for fulfillment elsewhere. These events play out as the Watergate scandal grips the country, causing an entire generation of young people to lose faith in institutions.

Lee’s direction emphasizes the humanity of all the characters. In spite of their questionable decisions, each experiences a moment of grace. For anyone nostalgic of the 1970s, The Ice Storm will cure one of such illusions. Social change brings liberation, but not without pain.

13. The Apartment (Billy Wilder, 1960)

Billy Wilder’s The Apartment stands as of the best films about loneliness and corruption in post-war America. Jack Lemmon’s opening narration sets the tone, “On November first 1959, the population of New York City was 8,042,783” as the camera pans over the city’s skyline as millions scramble off to their stultifying jobs.

Jack Lemmon plays C.C. Baxter, one of those nameless faces in the crowd, a put upon “schlub” slaving away for a gargantuan insurance company. During after hours he faces the indignity of loaning out his apartment to philandering executives.

Wilder emphasizes the mechanical nature of the corporate world with long shots of hundreds of desks lined up as the workers punch numbers and make phone calls. Meanwhile the top brass barks orders from their luxurious offices. Wilder’s sardonic fanfare for the common man teems with passion and emotional cruelty. Baxter’s lonely day behind the desk gets brief respites during interactions with the elevator operator Fran (Shirley MacLaine).

Eventually Baxter’s “favors” for the executives pay off, one in particular Mr. Shelldrake (Fred MacMurray), decides to promote Baxter. Much to Baxter’s chagrin, Mr. Shelldrake (a respectable family man) is having an affair with Fran.

The Apartment illuminates the dark shades of America life: being alone on Christmas Eve, the plastic veneer of marriage, and the struggle to connect. Wilder’s signature blend of humor and sadness resonate now more than ever.

12. Zabriskie Point (Michelangelo Antonioni, 1970)

Michelangelo Antonioni directed some of the most influential films of the 1960s including L’Avventura, Red Desert, and Blow Up, so his foray into American counterculture generated high expectations. Many hoped for a film that would connect with the young people like 2001: A Space Odyssey and Easy Rider did the year before.

American critics expressed befuddlement at Zabriskie Point, chiding Antonioni’s simplistic view of America, often pointing out the script’s immature dialogue. For example, the film opens with student revolutionaries screaming platitudes on liberation, making them look like crude caricatures of youth revolt.

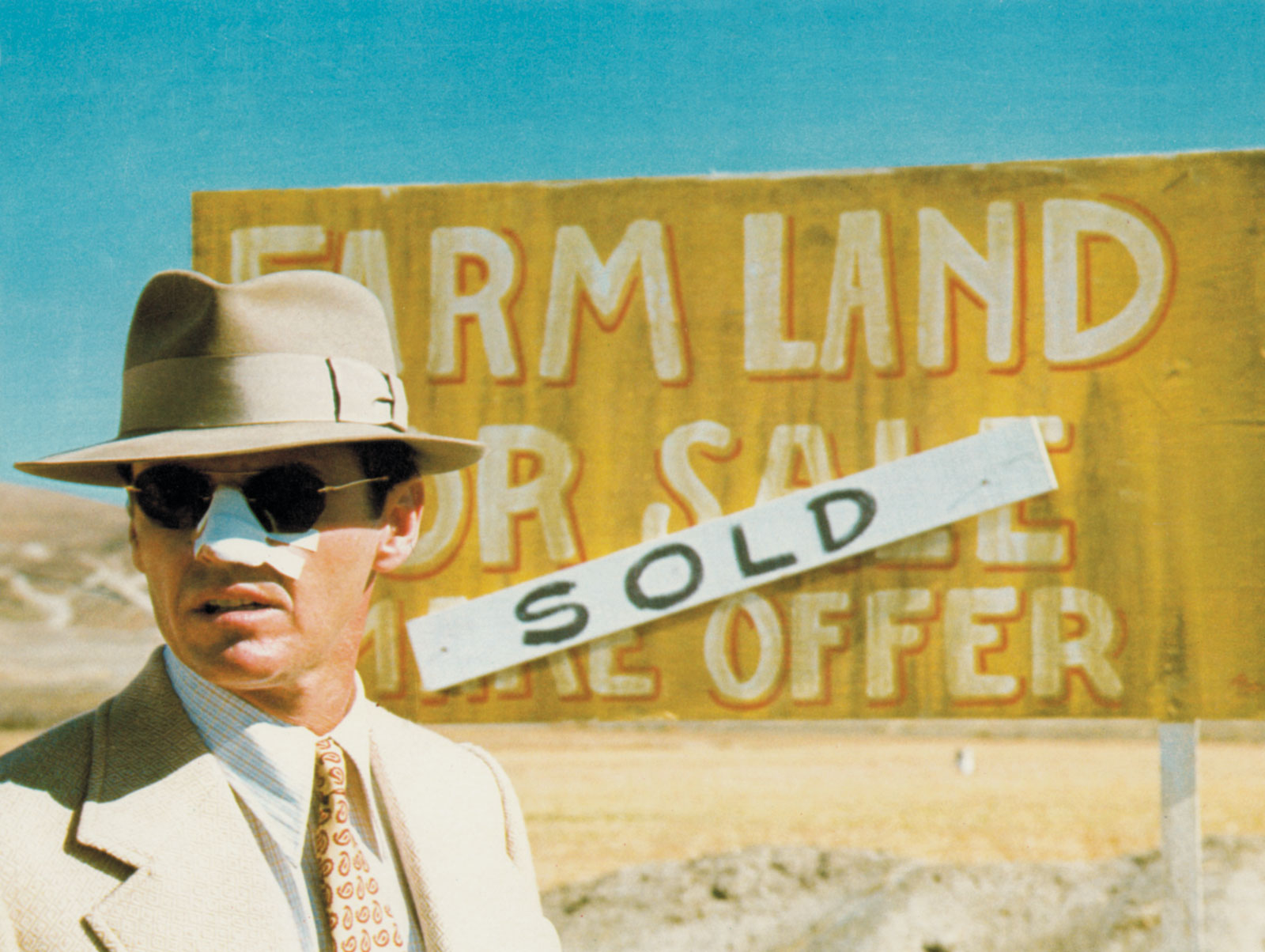

Antonioni’s elliptical structure follows a real estate executive played by Rod Tyler who personifies the establishment, while his attractive secretary Daria and a rebel named Mark lead aimless lives. Mark steals an airplane and meets up with Daria in the desert and they wander off to Zabriskie Point and fall in love.

The magnificent cinematography turns the geography into a character, one of the most unique landscapes ever put on celluloid. The spaced out music of Jerry Garcia and Pink Floyd stokes the surreal vibe of these sequences.

So Zabriskie Point portrays America as a land of soulless consumerism and lost children. All builds to an unforgettable climax of creative destruction.

11. The Dead Zone (David Cronenberg, 1983)

David Cronenberg’s adaptation of Stephen King’s novel about everyman Johnnie Smith (Christopher Walken) who awakes from a coma and discovers he can see into the future. A wintry tale in the best tradition of Edgar Allen Poe and Nathanial Hawthorne, Cronenberg crafted a unique horror film about the loneliness of gifted people.

At first Johnny uses his powers to prevent bad things from happening. He helps the local police track down a serial killer. He prevents a child from drowning. Eventually Johnny becomes overburdened and withdraws from the world until a chance encounter with a charismatic politician forces him to make a difficult decision.

Cronenberg’s direction and Walken’s emphatic performance are amazing. With the exception of one scene of grotesque gore, the gentle tone and sense of fate suggests the misunderstood loners will save the world. The Dead Zone is like Cronenberg’s version of It’s A Wonderful Life.

10. Stoker (Park Chan-Wook, 2013)

Set somewhere in the Midwest, possibly near David Lynch country, Stoker explores the sensual side of evil. Inspired by Alfred Hitchcock’s 1943 classic Shadow of a Doubt, Stoker offers a carnival of stunning imagery. Mia Wasikowska, Nicole Kidman, and Matthew Goode all deliver excellent performances in their incestuous love triangle of murderous intrigue.

Wasikowska plays India, a socially isolated teenager mourning the loss of her father. When her handsome Uncle Charlie shows up India’s world experiences big changes. Charlie’s shady history suggests he’s murderer, a family trait Charlie wants to pass on to India in a macabre twist on Cinderella.

Chan-Wook’s fluid camera movement and smooth transitions creates a sense of disorientation. Stoker presents an America Gothic of rich wheat fields, stately country homes, high schools made of brick, lush forests, and ghostly girls. A place where the present and past intermingle in unsettling verisimilitude, both seductive and frightening.

9. Atlantic City (Louis Malle, 1980)

Filmed on location in Atlantic City and South Philadelphia, Louis Malle envisions America as a place obsessed with its own mythology to fuel the desperate dreams of the young.

Burt Lancaster stars as Lou, an aging small time mobster who cares for an invalid woman and runs a minor numbers game. Lancaster adds a quiet dignity to a deeply flawed character who spends most of his time telling yarns about Al Capone and Bugsy Siegel.

When Lou’s attractive young neighbor Sally (Susan Sarandon) gets caught up in her estranged husband’s drug deal that went bad, he intervenes in a last attempt at the big score. Sally works at one of the new casinos in Atlantic City, the city’s latest effort to revitalize itself. Malle presents the world of casinos as drab and artificial, an impotent attempt at reinvention.

Malle allows his characters to evolve and have their moments, always keeping the camera at a respectable distance in a moody portrait of a city – and a country in transition.