With Lynne Ramsay’s miraculous Morvern Callar we are continually someplace else. In the cinema, outside of the cinema, in and out of time, passionately and profoundly in the reality of experience and most certainly in tactile transcendency.

A film of startling beauty and immense intellect, Morvern Callar may, for some viewers, bypass any immediate emotional response as its protagonist is such a multi-faceted and often ambiguous character.

Sympathetic one minute, border-line psychotic the next, Samantha Morton, in the titular role, is a whirlwind of expression and sentiment in one of the brightest and bravest roles of the noughties, a role that easily places her in the upper echelon of actors in hers or any generation.

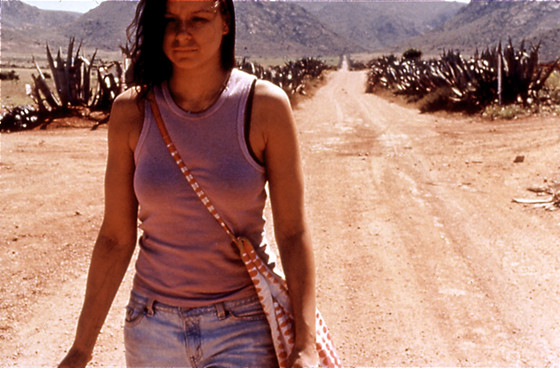

Adapted from contempo-beat Scottish writer Alan Warner’s unfilmmable 1995 cult novel of the same name, Morvern Callar begins in a small coastal town in the west of Scotland, where twenty-one year-old Morvern (Morton) works in a wearisome supermarket. Morvern’s best friend is the live wire Lanna (the absolutely astounding Kathleen McDermott, a non-actor, in her debut), and together the pair will sort of re-enact some of the prosaic road movie aphorisms, but only after Morvern makes a startling discovery on Christmas morning.

“Morvern Callar is intensely atmospheric. The film has a laconic, minimal script: Morvern says very little. She never gives an account of herself, and Ramsay and co-writer Liana Dognini won‘t help us out by providing the young woman with any discernible personality. We may not know whether to like her or deplore her conduct, but we can’t help but be drawn to her otherworldliness.”

– Ella Taylor, L.A. Weekly

Delusions of gender

I’ve always viewed the opening shot of Morvern Callar, perhaps incorrectly, as an homage to Bob Rafelson’s somewhat cynical 1972 drama, The King of Marvin Gardens. That film leads off with Jack Nicholson giving a despondent and mystifying monologue in the presence of a mysterious flashing light.

As Nicholson’s speech continues our awareness of the lighting and what it represents continues to puzzle and tease until it’s revealed that it’s an ‘on air’ light and that we’ve been hearing a dispirited late-night disc jockey talk-show host. Ramsay does a similar ploy to a much more startling and sinister effect.

A spectral off-camera light source instantly induces panic as it glows off the stirring face of Morvern Callar. She has just awoken to a mesmeric and horror show tableau, one lit by what, exactly? An alarm? A blinking ‘on air’ sign? Twinkling Christmas lights? Shockingly, it’s the latter as the horrifying half-light reveals the dead body of her boyfriend as a Christmas tree ringed with presents reflects in the gathered pool of his own blood.

“It just seemed like the right thing to do,” his suicide note reads. “I love you,” it also says, and “be brave,” and, “don’t try to understand.” He’s also left Morvern with money for his funeral, instructions for which are also in his note, along with a manuscript to his unpublished novel, and a number of ornately wrapped Christmas gifts.

Thus begins the tantalizing and sometimes baffling film, Lynne Ramsay’s second after her daring 1999 debut, Ratcatcher. Both confidently-made and courageous in their immersive and industrious artistry, announcing her as one of British cinema’s most daring and distinct talents. With a tone and style often eliciting comparisons to Catherine Breillat, Claire Denis, and Agnès Varda, Ramsay is certainly an artist of intelligence, imagination, and intensity.

“The movie doesn’t have a plot in the conventional sense, and could not support one. People like Morvern Callar do not lead lives that lend themselves to beginnings, middles and ends. She is on hold. Somehow, in some way, she’s stuck in neutral. The gray-brown tones of her life in Glasgow reflect her emotional habitat, and the bright colours of Spain cause her to wince in pain. She can only handle so much incoming experience at a time.”

– Roger Ebert

Snapshots of dangerous women

As Morvern mourns the loss of her lover, the audience is, on the surface, left in a sort of limbo. It takes some digestion for all the films parts to be properly assessed. Morvern spends the money for the funeral on herself, on a trip for her and Lanna to Ibiza. She also erases his name from his manuscript, replacing it with her own, and seeks its publication, successfully.

As a passive audience member it’s best to step back a little from this crazy-quilt pattern. While intellectually complex, like all Ramsay’s work, it contains heated and sensual pleasures that cannot be denied.

Questions about sexuality, class conflict, loyalty, identity, and lamentation all contribute to a many-layered parable.

Morvern and Lanna’s sojourn contains some of the self-discovery and coming-to-terms accountability you’d expect, yet nothing about their saga is predictable.

An appearance in Pamplona––during the Running of the Bulls, no less––plays out in surprising ways, the entire odyssey unfolds in an almost magical landscape, with steady assurance. It’s a marvel of story and sentiment. One passage in particular, where Morvern and a young man (Raife Patrick Burchell), whose name we never learn, but who is grieving the loss of his mother, finds brief but empowered kinship in Morvern, and their mutual longing.

It’s a sequence with almost no dialogue, but with eye-popping elegance and controlled restraint. It’s unforgettable and ephemeral. The ghostly glow in their bright, sad eyes speaks volumes without literally speaking anything at all. It’s a humbling and heartfelt moment, difficult to describe, but when seen, it overwhelms.

Also overcoming is the music Morvern’s boyfriend left behind in one of his many posthumous Christmas presents, this one in the form of a mix-tape that further connects the audience into the headspace Morvern inhabits (many sequences show Morvern wearing headphones as the audio-track reflects what she’s losing herself in).

Contemporary artists like Aphex Twin, Boards of Canada, Broadcast, and Can coalesce with classic cuts from the Mamas and the Papas, Lee Hazlewood, and the Velvet Underground, making for a cosmology that’s accessible and familiar.

It certainly, without putting too fine a point on it, suggests and disseminates the healing and curative qualities of music, as well as its restorative and transcendent potential. And cool points aside, it also helps draw us further into Morvern’s head space, a necessary move since she spends so much time soundlessly observing (incidentally, in Spanish, “callar” means silence).

Somewhere beautiful

A lucid attentiveness to Morvern’s world, to her pains and indignities, is given lifeblood via Morton. Her eyes and face are so expressive and celestial, detailing exquisitely her repressed emotions, and her savage strength.

It’s all right there in a performance comparable to the great silent film star Maria Falconetti (1928’s The Passion of Joan of Arc), whose greatest role, like Morton’s here, frequently focuses on the conditions of the mind. To perceive the world of Morvern Callar, like Joan of Arc, even, we must become a little like her, and thanks to these penetrating performances and luminous close-ups, we do.

Samantha Morton’s breathtaking tenacity is certainly possible partially because of her great trust in Lynne Ramsay––it certainly feels like a deeply personal project for both of them, as confirmed by what is shown onscreen––but surely Alwin Küchler’s supernatural cinematography also warrants much deliberation and love.

Küchler, who lensed all of Ramsay’s films to date, appropriates a bold visual sense that is tender yet unsentimental, and makes for a gritty realism with visual poetry that pushes it far past populist cinema experience and into the realms of high-but-approachable art.

To anyone who needs their faith renewed in the representation, allure, and importance of cinema as objet d’art, Morvern Callar is a studious, heart-piercing monument of feminist ideals, magnanimity, intelligence, and hope. Lynne Ramsay puts more truth and authenticity onscreen than in almost any other film in recent memory. The sometimes strange, often secretive, but genuinely unequalled heart of Morvern Callar exceeds cinema in its own veiled way. So vast and exceptional, it easily overshadows us all.

Author Bio: Shane Scott-Travis is a film critic, screenwriter, comic book author/illustrator and cineaste. Currently residing in Vancouver, Canada, Shane can often be found at the cinema, the dog park, or off in a corner someplace, paraphrasing Groucho Marx. Follow Shane on Twitter @ShaneScottravis.