The beauty of foreign film is to explore a world different to your own only to find that many concerns remain very much the same. Therefore, looking at universal themes through the perspective of another culture allows for a certain empathy to grow between peoples.

Experiencing different filmmaking styles and social customs from your own allows the mind to grow and worldview to shift, sharpening your understanding of the world around us. Additionally, the greatest benefit of watching world cinema is being able to travel the world from the luxury of your own living room, making it much more affordable than taking a cruise.

Nevertheless, when it comes to lists of top foreign films, a consensus can easily grow of what constitutes the best work of non-English language movies. In the process, many great foreign films can get overlooked.

For the more discerning among you, who are looking for movies that haven’t received the critical and commercial success that they so deserve, this list works to shed a light on some of the most criminally underrated. From the less-seen movies of established auteurs to the best of Eastern European cinema, this list will hopefully come in handy once the more conventional options have already been exhausted.

1. Autumn Sonata (Ingmar Bergman, 1978)

Bergman achieved his fame in the 50s, balancing naturalism and philosophy to devastating effect. The 60s saw him innovate in that decade like no other filmmaker (with the exception of Jean-Luc Godard).

Nevertheless, it is truly in the 70s and 80s when he learned how to combine both his deep understanding of the human spirit with rigorous formalism to make his most emotionally engaging films, with titles such as Scenes From A Marriage, Cries and Whispers, and Fanny and Alexander.

Overlooked among his later directorial efforts is the shattering Autumn Sonata, marking the only time that the two most famous people in Swedish cinema — coincidentally sharing the same surname — would meet. Ingrid Bergman gives a career-best performance in the movie, playing a fantastic pianist who visits her daughter only for the long-gestating skeletons in their relationship to come out of the closet to heart-stopping effect.

An excellent demonstration of how well Bergman could master the chamber drama — as seen before in his Silence trilogy — Autumn Sonata may perhaps be his best work, at least for those who are more naturalistically minded. What makes it so affecting is to how close-to-the-bone this fraught mother-daughter relationship is. Additionally, it holds the honour of milking the most dramatic tension from a recital of Chopin ever committed to film.

2. City Of Women (Federico Fellini, 1980)

Federico Fellini is a rightly acclaimed director, from his neorealist beginnings in La Strada and I Vitelloni, to his artistic highpoint with La Dolce Vita and 8 1/2, to a rediscovery of his childhood with the hilarious yet melancholic Amarcord. Nevertheless, critical consensus is that Fellini would never quite direct a film to match those heights again after 1973.

Lumped into the bloated but in-substantive category is City Of Women. This is unfair as it works as an excellent demonstration not only of Fellini’s pet themes — the unconscious, imagination, the influence of women — but as an older, somehow more fantastical version of 8 1/2.

Joining Fellini on his picaresque adventure is old pal Marco Mastroianni as an old businessman who, after observing a beautiful woman on the train, follows her to a hotel, which he soon realises is occupied by women and women only. With each room revealing new and unexpected delights, soon the protagonist is forced to overcome his prejudices in one of Fellini’s most inspired movies.

The gender politics might be a bit old now — especially Fellini’s satire of the feminist movements — but as an ode to the power of pure imagination, and the pull of women on the male psyche, City Of Women stands as an excellent summation of everything Fellini worked towards throughout his career.

3. Ivan’s Childhood (Andrei Tarkovsky, 1962)

Andrei Tarkovsky is generally considered to be the greatest of all Soviet Filmmakers. Eisenstein may have invented the montage in Battleship Potemkin yet Tarkovsky perfected what would later be termed as slow cinema. Among his crowning achievements stand epics such as Andrei Rublev and groundbreaking science-fiction such as Stalker and Solaris, yet his one film that doesn’t get quite the credit it deserves is his debut: Ivan’s Childhood.

Perhaps it is a sense of scale. Very much Tarkovsky’s smallest film, lacking the ambition of Mirror or the austerity of Nostalghia, it tells the story of Ivan (Nikolay Burlyaev) as he navigates the horrors of war.

Yet, it features many of the hallmarks that would separate Tarkovsky from nearly every other filmmaker — such as his nonlinear narrative, his use of dream sequences, and his excellent sense of pacing and composition, such as the unforgettable scene of the lovers together in the trees. In this film one can see the birth of a star.

Tarkovsky famously said that he made the film as a test, in his words, “to establish whether or not I had it in me to be a director.” The resultant work is not only proof that he had what it takes, but prophecy, going on to dominate the world of cinema for the next two decades.

4. Boyfriends And Girlfriends (Eric Rohmer, 1987)

An Eric Rohmer film would be a hard sell in a Hollywood pitch room. Featuring long, meandering conversations, usually about literature, philosophy and love, his films prioritise character over plot every single time.

This has led some to accuse the filmmaker of repetitiousness, but with each film he finds something fresh and exciting to say. This exploration of the human heart finds itself most gorgeously treated in Boyfriends and Girlfriends, which explores the affairs of four people amidst a “new town” on the outskirts of Paris.

More than any other director, Rohmer’s films have such an acute sense of geography to make the settings major players in the characters thoughts and desires — they are always shaped by the scenery whether they know it or not. In a sense, whilst seeing Mitterrand’s Grands Projets as having a noble intention, Rohmer criticises the ultimately soulless nature of some of the places he built as helping to further the moral vacuousness of the yuppies that occupy them.

In keeping with his aims of gentle social critique, Rohmer’s films exist as snapshots of the time in which they were made, making Boyfriends and Girlfriends, made in 1987, the ultimate highpoint of French kitsch, replete with an abundance of outrageously colourful outfits. The joy of a film like this, like all of Rohmer’s films, is to look beyond the seemingly obtuse surface to reveal a world of subtext lurking just beneath.

5. À Nos Amours (Maurice Pialat, 1983)

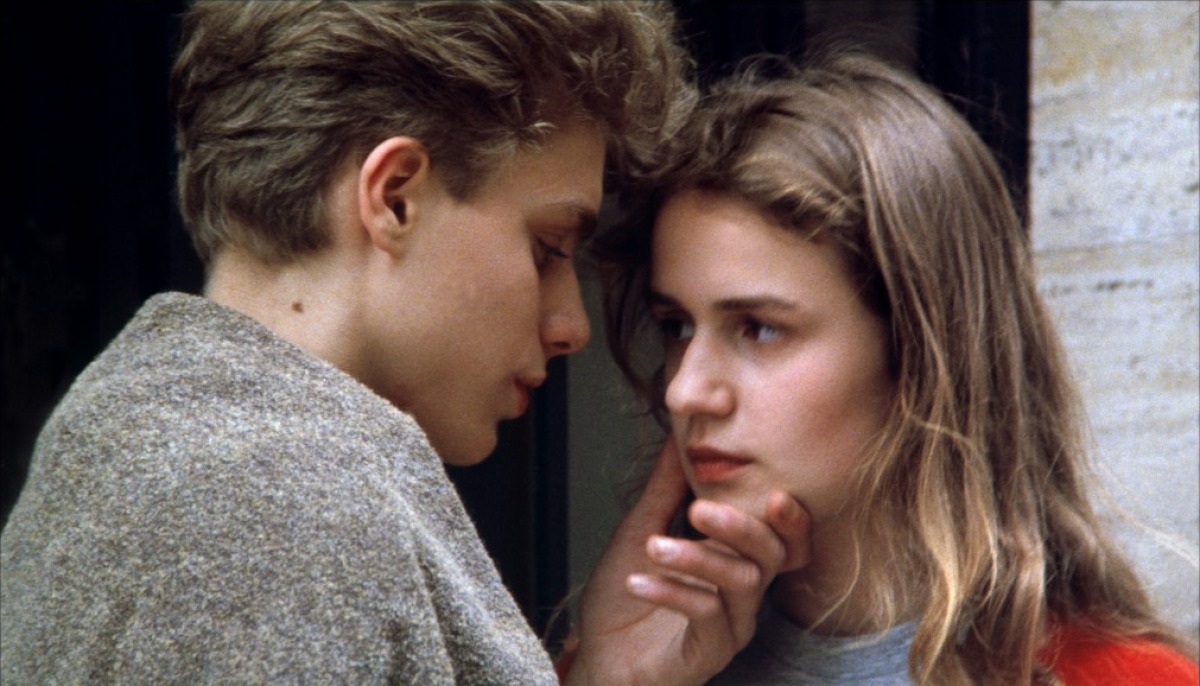

Made by the French iconoclast Maurice Pialat, famous for declaring the French New Wave to be a petit-bourgeois movement without merit, À Nos Amours is an uncommonly moving coming-of-age story featuring a fearless career-defining performance by Sandrine Bonnaire.

Looking for a feeling of direct truth in his films unburdened by boredom or sentimentality, Pialat would edit out all scenes he didn’t think weren’t ecstatic enough. This film, which sees a young girl trying to make sense of her place in the world, involving a series of unsatisfactory affairs with men, is the ultimate summation of that filmmaking desire.

In a career full of bold moves, À Nos Amours would see the director create his most iconic scene, when unbeknownst to the actors involved, he appeared mid-filming at a dinner scene only to scream and shout at them, making the reactions involved as personal as they are professional, expertly bleeding the line between documentary and fiction.

As beautifully striking as it is difficult to watch, À Nos Amours is the quintessential film when looking at the concept of sexual awakening and what it means to be a woman and therefore to be an object of desire. To be as ugly as it is dazzling is a feat that only the immense auteur Pialat could pull off. Its high time his work deserved more recognition.