Terrence Malick’s late period, which runs from “The Tree of Life” to “Knight of Cups”, has had a strange life. It was universally hailed in the beginning and then rejected with “To The Wonder” and “Knight of Cups”; people have started to sneer, and some people have taken a revisionary angle where they only value Malick’s work in his first three films: “Badlands”, “Days of Heaven” and “The Thin Red Line”.

Many people are baffled; some never gave up on Malick, some people think he makes the same film every time (nothing could be less true), and some people think his brand of cinema is old (nonsense).

Critically, his approval has plummeted, but truthfully, there are reasons to be more and more in love with Malick with every film he makes. The progression that has happened from “Badlands” to “Knight of Cups”, the progressive abstraction, did not bring vagueness or confusion or indulgence, but rather a clear aesthetic development and a cinematic sincerity that few authors have, as well as a genuine sense of experimentation and avant-garde.

“Knight of Cups” is the culmination of Malick’s path, and it is his best film; not on a subjective level of taste, but in terms of perfection of his poetic filmmaking style, of his full understanding of the philosophical undertones of his cinema, along with bold camerawork that he very rarely employed and the new epistemic complexities to be found.

1. Stream Of Consciousness Filmmaking

When Malick began making films, his style was much more narrative and linear. In many ways, it made him a more philosophical descendant of the western and the melodrama, a New Hollywood filmmaker with a penchant for transcendent storytelling and natural imagery. Over the years, his style has become far more rarefied, and he has moved away from the literal to sink into the theoretical and the metaphorical.

The voiceover is one of the most distinctive features of Malick’s cinema; it began with “Badlands”, where it was used in a conventional way, then it became progressively impressionistic, from “Days of Heaven” to “The Thin Red Line”. It started to represent a completely interior universe in “The New World” and “The Tree of Life”, and in “To The Wonder”, the voiceover emphasized its role in the making of the meaning of the image; it became a philosophy and creation and poetic in every sense of the word.

In “Knight of Cups”, as the metaphorical quest for the pearl unravels, the progress toward transcendence is punctuated by the voices of characters, even non-existent characters (the King, for example), which are part of the metaphorical context but not part of the plot.

Even the chaptering is part of the stream of consciousness; the names of the chapters, such as ‘The Moon’, ‘The Hanged Man’, and ‘The High Priestess’, are all interpretative frames where Malick can insert his flow of images with a certain degree of structure. “Find your way. From darkness, to Light”; “Remember”; “My son”; these are all are touching upon the underlying meaning of the peregrine’s journey of the prince and the pearl in the East, from the perspective of Malick’s imagination and not as much through the adherence to storyline or plot.

It is clear from the interviews of the actors who didn’t know who they were playing, from the gentle way in which every image blends into the next, that Malick is lifting every second of the film from an internalized perspective, and this also plays into the allegory.

2. Purely Allegorical Filmmaking

In order to watch “Knight of Cups”, a set of cultural references is required, particularly from Gnostic philosophy. The difference between this film and all the others from Malick, is that before, there was a clear distinction between the allegorical and the literal, the reign of the story where things happen, and the reign of the hyperuranium where the ideas develop and the allegories become image.

For example, “The Tree of Life” was very divided between the microcosm of the trivial, and the metaphorical and philosophical splendor that invades the screen during the creation sequences and the angelic visions.

It’s not like “To The Wonder”, where Malick tried to capture the essence of a transcendent sentiment through the trivial and the mundane; here, every space and every man-made or natural element of the plot carry a symbolic value that refers to an intricate set of references, which create a Dante-like canvas of the entire philosophical pantheon of Malick.

Thus, we start with the film’s poster, featuring a painting by German gnostic mystic Dionysius Andreas Freher, and then we have the nod to Hans Jonas. The film hasn’t even started yet, and already it is set into an ideological framework. We have the desert, which in a way is Egypt, which in gnostic tradition coincides with the material world.

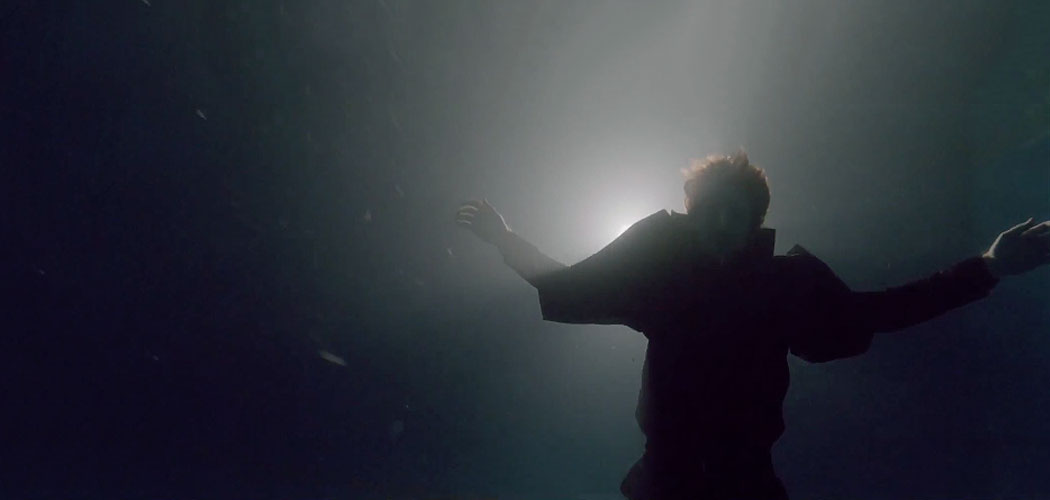

We have many sequences of coming in and out of the water, as the water is a symbol of time, becoming, and corruptibility, in gnostic tradition. It is clear that the final scenes, with the final emergence from the sea and the desert, is the great liberation from the sufferings and from materiality and impurity.

Every shot of the highways, even the scene at the modern art museum with the peculiar art installation of toy cars frantically moving in a miniaturized reconstruction of an urban environment, echo gnostic ideas, of the universe being a prison and a maze, and that the Earth is the deepest and most intricate part of it.

The scenes with Christian Bale in elevators evoke brief but significant small ascensions, and the tendency of the world toward transcendence, much like Gothic architecture in the Middle Ages.

Instead, Hollywood becomes Babylon, the Augustinian city of the Devil that is juxtaposed to the city of God, which Bale’s character keeps looking at in the many shots in which the camera is slightly orientated toward the sky; it gently glides, as if the soul of the character is leaving and wandering the world. Even a dog swimming after a toy becomes an allegory for the knight looking for the pearl, immersed in the world of materiality, incapable of reaching it.

This tendency toward allegory, which was never concealed in Malick’s cinema, is more powerful and reaches its strongest iteration in this film because Malick renounces the presentation of nature as a vehicle for the glory through pure observation.

Instead, trapping the film in an artificial environment can curve every element to a precise function that is not apparent at first, but reveals itself once the correct interpretational key is found. The pilgrim’s progress from this world to the one that is to come, as is stated in the beginning of the film, is truly the entire film; it is all that is onscreen.

What about the tarot cards? Well, they illustrate the path of the soul from instability, to the Moon, to the fracture that opens between the physicality of the soul and its contemplative nature, to the Hanged Man and the Hermit. There is the adulthood of the soul, Judgment, a new stability that coincides with fatherhood; there is pure spirituality, the Tower. There are the two kinds of revelations; a hedonistic one, The High Priestess; and a purer one, Death. And then finally, there is Freedom.

3. A Complex View On Femininity

Things have changed for Malick regarding his actresses, from the young wide-eyed Americana beauty of Sissy Spacek, to the angelic beauty of both Brooke Adams and Jessica Chastain. Incarnations of divine grace are seen with the women in “To the Wonder”, marking the first signal of change in his gaze, to the complexity exhibited in “Knight of Cups”.

Pop advertising makes several appearances in the film, as images of female bodies confound, depress, and elevate Malick’s view; those bodies, in video clips and billboards, and in the parties of the wealthy, remind him of beauty that is buried underneath the glittery surface of luxury.

In a land of perdition, of prostitution, of carnal enjoyment without spirituality, Malick is not afraid to look at skirts, at legs, and at sexual features through his camera; sensuality plays a part and is philosophically valued by Malick for the first time.

Malick also elaborates on the many natures of love through the encounters of the protagonist, when he is lost in the pleasure given to him by strippers and prostitutes; these are featured in the chapter ‘The High Priestess’, or when love produces in him only emotional turmoil. The first level and the lowest one is shown in ‘The Moon’, in his relationship with Imogen Poots’ character, and the emotional maturity and the culmination of the terrestrial experience in his marriage with Cate Blanchett’s character.

The first illumination in seen in Freida Pinto’s character, as the serene model that indicates a path of light to him, and Natalie Portman’s character donates to him the possibility of complete abnegation, repentance, and agape. Women in “Knight of Cups” are the crucial moments of the earthly experience and the best indication of transcendence, as they are no longer just a vessel for the divine grace.

4. De-Personalization Of The Actor

The process began with “To The Wonder”; we barely know the names of the characters as they are metaphors for all searchers of love, but the film still revolves around what happens to them, and this progressive abstraction comes to a new level in “Knight of Cups”.

Even though there is some background information about Rick – who his brother is, who his father is, things that have happened to him in the past – he is not really Rick. He is the Knight of Cups, and he is a walking metaphor. He is essentially male in his gaze, which is not because of his particular perspective, but rather just Malick’s perspective; the pilgrim’s perspective.

In being a humble pilgrim, Christian Bale is the essence of all mankind and his life is spent witnessing and experiencing. His gaze is all that matters, his body is transfigured as the medium through which the soul walks through the world, and for the first time, we perceive that the film is completely independent from his character, as the character is only the point of connection.