The Eighties were a truly intriguing time for cinema. While Americans buried the auteur driven films of the Seventies with glitzy, glamorous films influenced by rock videos, world cinema began to grow ever more introspective.

Just compare “Rambo: First Blood II” with “Come and See.” Both are war films, both were released in 1985, yet they show the crucial divide between popcorn driven American films and the introspective, almost harrowing films happening throughout the rest of the world.

It seemed as though no one was willing to bridge the gap, to make grand films the way they used to, the kind of films that should be shown in big old movie palaces. No one seemed to interest to in stimulating the heart, mind, and funny bone, all the while delivering pure entertainment.

Then came Amadeus.

Amadeus proved that they could make them like they used to. In fact, they could make them bigger and grander then ever before. Of course, it took a European director to marry the two sensibilities together and bridge the gap. Milos Forman, that pioneering Czech director who gave the world One Flew Over The Cuckoos Nest, set out to create the greatest music film ever produced. In actuality, he made the greatest film of the decade.

Here are six reasons why Amadeus is the greatest film of the 1980’s.

6. The Story. The Glorious Story.

Some men are cursed with greatness, while others lack the talent to achieve greatness. Some men a cursed with a desire for fame, while others just naturally achieve it. Every man harbors jealousy to those who are better than them. There is nothing new to this story. It’s as old as time itself.

Amadeus takes this story and completely reinvents it, pitting one man’s jealousy of another’s talent against that same man’s love of that other’s talent. How can you hate the man who creates such lovely music?

When we meet Salieri, he is an old man attempting suicide. It is an atonement for sins that we will learn about as the films progresses. He survives and is sent to an asylum where he is visited by a kindly Father whom Salieri wishes to hear his confession.

Before he does this, however, he asks the priest if he knows music. He plays the priest several melodies that are completely lost upon him. Finally, he plays something that the Father instantly recognizes. He asks Salieri if he wrote that delightful melody. Salieri grows sullen and replies, “No, that was Mozart.”

Thus begins the enthralling tale of an overly ambitious court composer whose own talent is slim. His entire world is shattered with the arrival of the young Mozart, a prodigy who becomes the talk of Vienna. Mozart is crude and playful, nothing like the stoic Salieri, who cannot believe that God would have given such a gift to a person as lewd as Mozart.

Mozart seeks Salieri’s influence in the court and the two become ‘friends,” all the while Salieri does everything he can to stop Mozart’s advancement in society. The only problem is Salieri loves Mozart’s music more than anything he’s ever heard. In one of the greatest sequences, Salieri reveals that it was because of his influence that Mozart’s “Don Giovanni” was only staged six times, yet Salieri himself went to every performance.

This duality is something that all men share. We can all harbor both love and hate for the same person. We all long for something others have that we don’t. This is especially true for artists. Creations and creators can often differ greatly. Yet, having the power to destroy the creator while longing for more of the creations is something that is unique to Amadeus.

5. Old School Cinema Never Dies

Amadeus was one of the last of the great American New Wave films. It was an auteur driven period piece based off of a stage play, produced four years after the crash of the old Hollywood (Heaven’s Gate) and seven years after the birth of the blockbuster (Star Wars). In reality, Amadeus had no business being made in 1984.

The ten highest grossing films of the year included the likes of Beverly Hills Cop, Police Academy, Ghostbusters, and The Karate Kid – all of them escapist fantasies that aimed for a mass market and high returns. Though some of these have become acknowledged classics over the years, none of them aimed to be earth shattering. They diluted the art to enhance the pulp and audiences couldn’t get enough.

Then, dropped into the middle of all this like an ancient relic, comes Amadeus. It had the look and feel of films like Barry Lyndon and The Taking Of Power by Louis XIV, and was filled with bravura performances akin the films of Olivier and Welles. It was almost three hours long and contained no exciting action sequences, long opera performances, and a subject who is mostly known today through marble sculptures and background music. Yet, the film was a critical and commercial smash.

It won an astonishing eight academy awards, including Best Picture, Actor, Director, and Adapted Screenplay. More importantly, it proved that classic film techniques and storytelling were alive and well, and that director driven, auteur films could still be huge successes.

4. Representing The Past As Never Before

Most of the time throughout Hollywood history when filmmakers decided to take their audience to the eighteenth century, things tended to look stagey. Costumes look like costumes and the settings look like sets. Rarely did the viewer ever feel truly transported back in time.

The one film that truly broke this stereotype was Stanley Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon, a commercial flop that has sense grown to be regarded by many as the most beautiful film every created. Those few who saw the film were effortless transported back in time. Nine years later, Amadeus achieved the same effect, only to mass appeal and success. Yet, Amadeus takes it one step further by portraying historical figures as average people.

Milos Forman broke with tradition and hired American actors to play the major roles, a move which immediately made the Viennese royalty more approachable. The sheer fact that noted character actor Jeffery Jones plays the Emperor in the film really breaks down the stoic barriers that so many ‘royal court’ films posses.

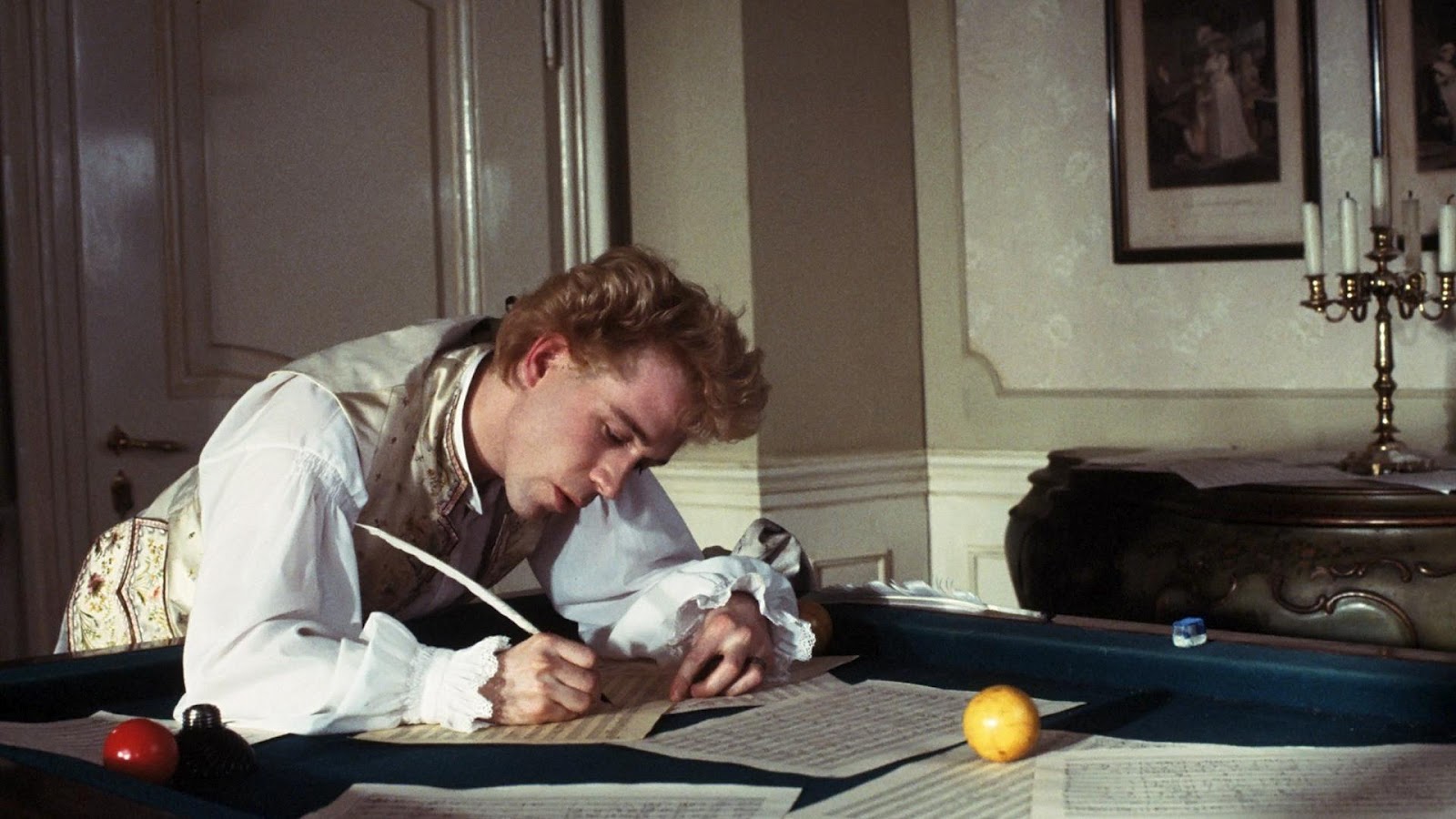

Milos also fills his film with adolescent buffoonery. Never is Mozart treated as a figure of great standing. He is, essentially, a young man with raging hormones, who is gifted (or cursed) with a brilliant musical mind and a progressive, forward thinking ambition that is destined to bring him ruin. Just compare Tom Hulce’s Mozart to Gary Oldman’s Beethoven in Immortal Beloved to see how differently this great composer was portrayed.

3. Captures The Nihilistic Underbelly Of The 1980’s

Antonio Salieri is a quintessential villain for the eighties. His feelings toward everyone remain ambiguous, and his intentions change based upon opportunity. His sheer disregard for emotion when posing as Mozart’s father and commissioning a requiem mass (a piece Salieri somehow knows will kill him) is staggering. Once Salieri resigns himself to a hatred of the God has forsaken him, there seems to be no line he won’t cross.

In one of the great scenes that was cut from the theatrical release, he humiliates Mozart’s wife by making her think she must sleep with him in order to gain his influence to get Mozart a job. Once she is bare chested and on the verge of removing the last of her clothes, Salieri rings the bell for his attendant to come in and see the woman out. It is a stunning sequence that shows the depths of depravity that Salieri becomes willing to stoop to.

2. Captures The Gleeful Abandon Of The 1980’s

Where as F. Murray Abraham’s Antonio Salieri is the perfect 80’s villain, Tom Hucle’s Mozart is his counterpoint. Mozart is playful and full of life. He is a like a character from a Truffaut film, and yet could be a member of The Breakfast Club. His spends money with gleeful abandon and drinks too much. He is a lost youth who is reveling in the prime of his life. Strip away the years and there is little separating him from the members of the brat pack.

Take, for example, the famous party scene in which party goers call out different composers for him to mimic (or really, mock). If you were to change the clothing and the setting to that of a high school party, yet leave the rest of the scene untouched, you could easily slide it into the films of John Hughes or Cameron Crowe from that era.

There are many other scenes peppered throughout the film that show the influence of the decade, but they are cleverly woven into the fabric of the period and only enhance the feeling of transportation.

1. The Greatest Acting Of The Decade

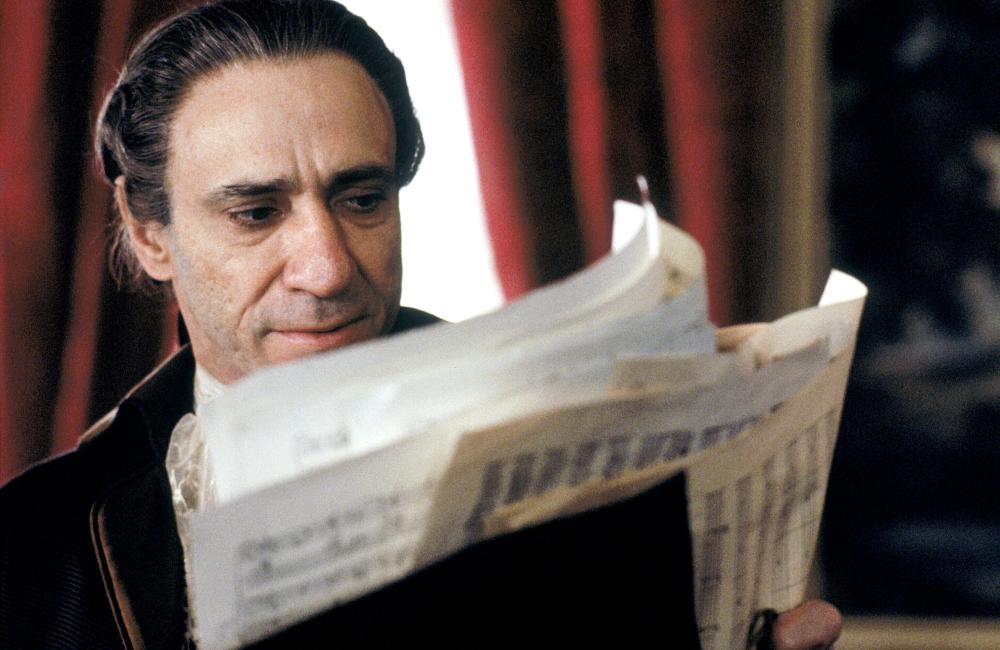

If there is one thing the cinema of the 1980’s gave us, it was great performances. Who can forget Robert DeNiro in Raging Bull, Michael Douglas in Wall Street, or even Dustin Hoffman in Tootsie? But when it comes down to it, F. Murray Abraham and Tom Hulce give the greatest performances of the decade in Amadeus.

Each actor brought something completely different to their roles, yet the chemistry between the two of them is electric. They act as both mirror images and polar opposites. When they conduct their respective symphonies, Forman shoots them from the same angle so the difference in their performances can be studied in full view. You can clearly see as Abraham shows Salieri’s subtle lack of confidence in his work, while Hulce’s Mozart rides his ecstasy into the dizziest heights of conducting.

When the academy was forced to pick between the two of them, the nod went to Abraham for tackling the tougher role. His work as an old man, buried beneath some of the most convincing prosthetics ever filmed, is truly the jewel in his crown as an actor.

Of course, both Abraham and Hulce are supported by a stellar cast, including the aforementioned Jones as the bumbling Emperor Joseph II, and the ravishing Elizabeth Berridge as Mozart’s wife Constanze. Though they work toe to toe with the two stars, they never take away from their thunder.

The reason why Amadeus remains a classic with is the acting. The performances stick with you long after you’ve left the theatre. They resemble us so much that they stick around and pop up from time to time.

So, naturally, the number one reason why it is the best film of the 1980’s is the acting!

Author Bio: David Brimer is a professional musician and writer from Florida. He has toured the world with artists as diverse as Jackson Browne and Hanson, and has published a few short stories in small literary magazines. He is a self-professed cinephile who loves pure cinema.