For those (of us) who grew up in the 80s, that seemingly carefree, wonderfully campy era is fondly remembered, whether for many Saturday morning cartoons or for equally numerous cult movies of various genres.

But, let’s leave the popular and the acclaimed aside for now and step into the zone of obscure cinema, one film per director and avoiding the titles that have already appeared on this writer’s previous lists.

1. The Knight (Lech Majewski, 1980)

“… a haunting, austere parable that has been directed with assurance by Lech Majewski, whose flair for starkly poetic compositions often manages to outshine the elliptical quality of his material.”

(Janet Maslin, New York Times, 1983)

And still, “The Knight (Rycerz)” is criminally underseen, the subtitles unavailability being one of the main reasons. However, this surreal adventure – Majewski’s sophomore flick – can be enjoyed on a purely visual level.

Proving that a picture is worth a thousand words, it looks like some mysterious medieval tapestry brought to life. Accompanied by the brooding ambient music, the characters woven of mostly black, white and crimson threads move against the backdrop of deeply green forests, stone castle walls and sandy dunes and beaches.

Reminiscent of Sergei Parajanov’s masterpieces (to a certain degree), the film follows young knight on his quest for a legendary golden harp with healing powers. From a weird dance of the king’s courtiers to ritualistic orgies akin to an avant-garde performance, Majewski takes us on an arduous, yet enlightening journey that seems like a gloomy dream.

2. The Bloody Lady (Viktor Kubal, 1980)

The notorious Hungarian Countess Erzsébet Báthory spent years in Čachtice Castle, so the Slovaks were (and are) quite familiar with the horrifying legends about her. Inspired by those tales, the Czechoslovakian director Viktor Kubal spun a nightmarish fairy tale about the most prolific female serial killer.

His pseudo-historical horror-dramedy “The Bloody Lady (Krvavá pani)” is completely dialogue-free, so it communicates via the minimalist imagery and the evocative score by Juraj Lexman. At the beginning, Erzsébet is the antithesis of a ruthless noblewoman – she loves and is loved back by men, plants and animals. However, after (literally) giving her heart to a young lumberjack, she loses control (and soul), whereas her maid’s accidental mistake sets the wheel of madness in motion.

Peppering the story with twisted humor that involves anachronistic jokes and Disney parody, inter alia, the author shifts part of the blame to the Countess’s (male) accomplice. The murders happen off-screen in most cases, but Kubal doesn’t shy away from depicting the “rejuvenating” blood bath.

A peculiar experiment which the experienced audience will appreciate.

3. Zigeunerweisen (Seijun Suzuki, 1980)

Titled after Pablo de Sarasate’s composition for violin and orchestra, “Zigeunerweisen” brings the story about a suave professor of German, Toyojiro Aochi, his disheveled colleague, Nakasago, and their entanglement in (imaginary?) love triangles with three women, two of them being played by the same actress.

It sounds like the simplest of plots, but it most definitely is not, considering the bunch of enigmatic characters, voices coming out of nowhere, recordings of the aforementioned Spanish virtuoso’s mumblings, and a bizarre fetish best described by the line: “You caress me as if you were sucking my very bones.”

As the basis for this film (the first part of Taishō Roman Trilogy), Seijun Suzuki, famous for being fired from Nikkatsu Studios after finishing “Youth of the Beast”, takes Hyakken Uchida’s novel “Disk of Sarasate”. Together with his screenwriter Yōzō Tanaka, he raises a grandiose construction whose warped elements are welded with the irrational logic of feverish dreams.

From the intellectual angle, he addresses the assimilation of Western culture into Japan and creates a challenging puzzle rife with perplexing symbolism.

4. American Pop (Ralph Bakshi, 1981)

Along with “Fire and Ice”, “American Pop” is the pinnacle of Ralph Bakshi’s sophistication, both direction and aesthetic-wise. Simultaneously, it recounts the tale of four generations of immigrant family of musicians and the development of American popular music from the 1900s to the 1980s, while touching upon the social issues and changes.

Anti-Jewish pogroms, the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, burlesque and mafia, the world wars, the Kent State shootings, the beatniks’ philosophy, drug abuse and Jimi Hendrix’s performance all find their place in the simple narrative that pulses with irony, black humor and poignancy.

The emergence of certain genres and famous songs is credited to fictitious characters – doubles of celebrities such as Janis Joplin, Bob Dylan and Jack Kerouac. Ever ready to experiment and true to his gritty style, Bakshi utilizes a rotoscoping technique, archive footage, sketchy passages, as well as mind-blowing psychedelia.

5. A Man Who Ate a Wolf (Đorđe Kadijević, 1981)

Treated with disrespect by fellow villagers, a talented cooper Aleksa is unable to devote himself to the art of xylography. Many unfinished orders bring him into difficult financial situation and force him to move out of the leased workshop. After his sculptures (previously left in snow to rot) are burned by a vengeful brawler, he leaves for the woods (of Brueghelian beauty) to mold the largest trunk into his magnum opus… at any costs.

Metaphorizing an artist’s struggle in the reactionary society (and personifying his muse as a mute girl), Đorđe Kadijević depicts with chilling precision the Serbian mentality at its best and at its worst – not only through Aleksa’s surroundings, but through his capricious character as well. More than three decades later, his film hasn’t lost its relevance, given that the creative people are still marginalized, ridiculed and even threatened by the ignorant in power.

Notwithstanding its made-for-TV production values, “A Man Who Ate a Wolf (Čovek koji je pojeo vuka)” is neatly shot, superbly acted, tightly written and strongly directed piece of cinema.

6. Silvestre (João César Monteiro, 1981)

A lovely and gentle nobleman’s daughter, Sílvia (brilliant debut by then 17-yo Maria de Medeiros, later of “Pulp Fiction” fame), is supposed to marry a boorish landowner. Shortly before the wedding, her father goes to visit the king, instructing her not to let anyone in the house. However, she ignores his orders and opens the door to a mysterious stranger – at that point, the story takes a dark turn.

Drawing inspiration from the medieval traditions of his country and resorting to various stylistic “gimmicks”, Monteiro delivers an unorthodox, fairy tale-ish drama of fragmented narrative and outstanding aesthetics. Coded in its own logic, his vivid “picture-book” really does look “the way an illiterate shepherd who’s never seen a movie might visualize a storyteller’s campfire tale”, in the words of Nick Pinkerton of The Village Voice.

“Perverse poet” of the Portuguese cinema, as Monteiro is frequently called, helms with a deft hand and ironic attitude, with the crew in Bressonian mood and action scenes “hidden” in freeze-frames.

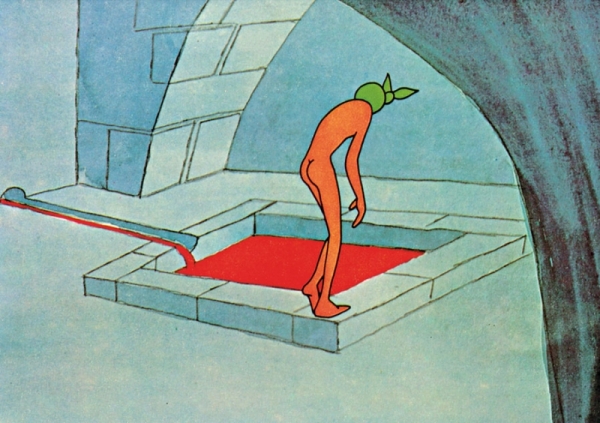

7. Chronopolis (Piotr Kamler, 1982)

“Chronopolis” is truly a “rad stuff”, as one of the IMDb users puts it. This unique, philosophically inclined stop-motion SF-phantasmagoria may be the shortest (and the most cryptic) entry on the list, but it is fascinating all the way through.

Following a short introductory epigraph is an abstract “story” told in inarticulate sounds and images of mythical, otherworldly qualities. Whether you understand that “language” or not is completely irrelevant – the immersive, meditative experience is what counts.

Draped in the color of sand, “Chronopolis” is an introspective, thinking man’s film asking many existential and metaphysical questions, but leaving the answers and interpretations to the viewers. Intriguing in its persistent silence, it seems like an enlightening vision of the past, the present and the future colliding in the fateful encounter of refined demigod creators and a man searching for the ultimate truth.

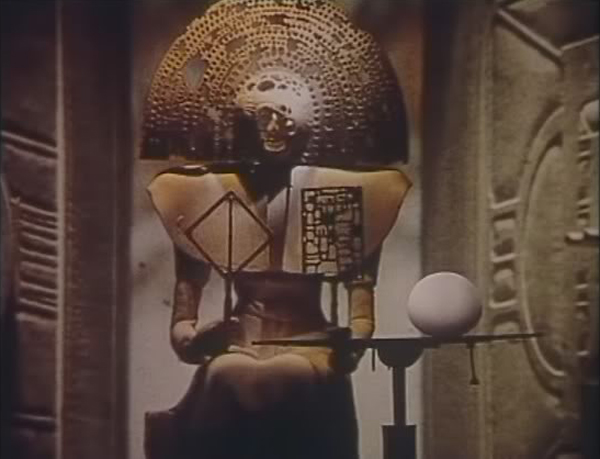

8. Time Masters (René Laloux, 1982)

This may sound very corny, but they really don’t make them like they used to. Laloux (1929-2004) has directed only three feature films and yet, each one of them is extraordinary in its own right.

His sophomore effort opens with the cool synth theme and takes us into the distant future, on the planet Perdide (whose name sounds pretty much like the Spanish word for ‘lost’ and not without a good reason). A vehicle crash renders a little boy alone with a “mike” – a transceiver through which he keeps contact with his father’s pilot friend Jaffar who is his only hope for salvation.

Based on Stefan Wul’s novel “The Orphan of Perdide”, “Time Masters (Les maîtres du temps)” is an outré adventure across the vast universe, ending with an unpredictable and paradoxical twist. Wildly imaginative, it brings to life Mœbius’s wonderful designs, including bizarre creatures, mystifying alien vistas, singing water-lilies, retro-futuristic architecture and Arzach’s cameo. More importantly, it subtly conveys all the right messages, stimulating both mind and heart.