The process of discerning what films are indeed “unique” is a slippery one. When you consider how cinema as a history has gone, films do influence other films, so, it’s quite a task to find exactly which films best disregard influence and exist as wholly their own creations.

Therefore, another characteristic of a film that is “unique” is also its lack of influence on other films. This is most likely as a result of the sheer boldness of a wholly individual film, it appears to be “too risky” for other filmmakers to follow in its direct path. These are the films that exemplify “uniqueness” the best and stand out distinctly in cinema’s history.

1. Dreams That Money Can Buy by Hans Richter

A film that has been grossly forgotten, this 1946 gem is a work of many notable authors. Hans Richter, who is credited as the film’s director, was famously one of the members of the Dada art movement, producing paintings for Dada events between 1917 and 1919.

In 1920, in pursuit of a “Universal Language” Richter and the Swedish painter Viking Eggeling wrote a manifesto which defined abstract art as a language understood by all through basic human perception, transcending known language and political barriers.

This artistic abstract language Richter desired proved the basis for the ultimate vision that is Dreams That Money Can Buy, a film about a man down on his luck who decides to sell people dreams for cash.

Of the authors, as mentioned earlier, are legendary artists such as Max Ernst, Fernand Leger, Man Ray, Marcel Duchamp, Alexander Calder. These men made art in their lives ranging from painting, sculpting, writing and, of course, filmmaking. Each authored one or two of the “dream sequences” that occur in the film.

As a result of this conglomeration of artistic authorship, the film proves to exist far from anything produced in cinema prior to or after. An unparalleled feat of abstraction that does in fact speak a language, understood through the combat of sight and sound.

Can be found on YouTube.

2. Playtime by Jacques Tati

Impossible to compare with any film, Tati’s masterwork is one that deserves to be viewed over and over again. Shot on 70mm, and featuring no close-ups or really even medium-shots, the film is an exercise in the interpretation and reaction of a kind of “scatter-shot” which does not direct attention visually.

Wide and using the entire frame, every moment of the film features all sorts of occurrences as a meticulous soundscape proves to further complicate, and overstimulate, any sense of understanding what is being pursued. So, Playtime is the ultimate example of a film “giving more upon each viewing” in that each frame is crowded with information to be observed.

To describe it simpler, the film follows bodies of people as they navigate a Modern Paris. Of those people is Tati himself, playing his legendary alter-ego Monsieur Hulot as he drifts through an urban landscape that surprises and confuses him. This one is exactly for the people that want to become overwhelmed and oversaturated in an essential, interpretative observational cinema experience.

3. Walden by Jonas Mekas

The ultimate example of a masterwork of “the home movie” Mekas’ extensive film catalogues years of his own life, over the course of about 3 hours. Another way to describe the movie could be calling it “an experimental home movie” or something along these lines.

Episodes in the sections of time are given title cards of description, followed by moving images seemingly on fast forward with an audio track that sometimes features music and sometimes Mekas’ own voice in reflection, commenting on parts of his life that he captured on film.

In its presentation, the film is a contemplation on time and the “speed” with which it passes, how dense a spectrum of time can be yet how fleeting individual moments of life are nonetheless. Surprisingly joyous and filled with beauty, profound in its scale Mekas truly earns his illustrious “godfather of avant-garde cinema” title.

4. F for Fake by Orson Welles

One of the later films of Welles’ titanic filmmaking career and without a doubt one of his best, F for Fake is a genius work of cinematic invention and introspection.

The film has often been called the “ film” in that it functions as a classic documentary that informs on the world of art forgery, specifically the art forger Elmyr and the characters that surround him. Yet Welles himself also participates as an on-screen narrator and guide, attempting to grapple with the endless lies and deceits that occupy Elmyr’s world, and therefore, the contemporary world as a whole.

What is so unique about the film is how tangled Welles as a person becomes with its material as what starts as a dense portrait of an art industry built on accepted lies, transforms into an investigation of Orson’s own life and career as a “deceiver” of sorts. So, fact and fiction really blur together in this paradoxical puzzle piece in cinema history.

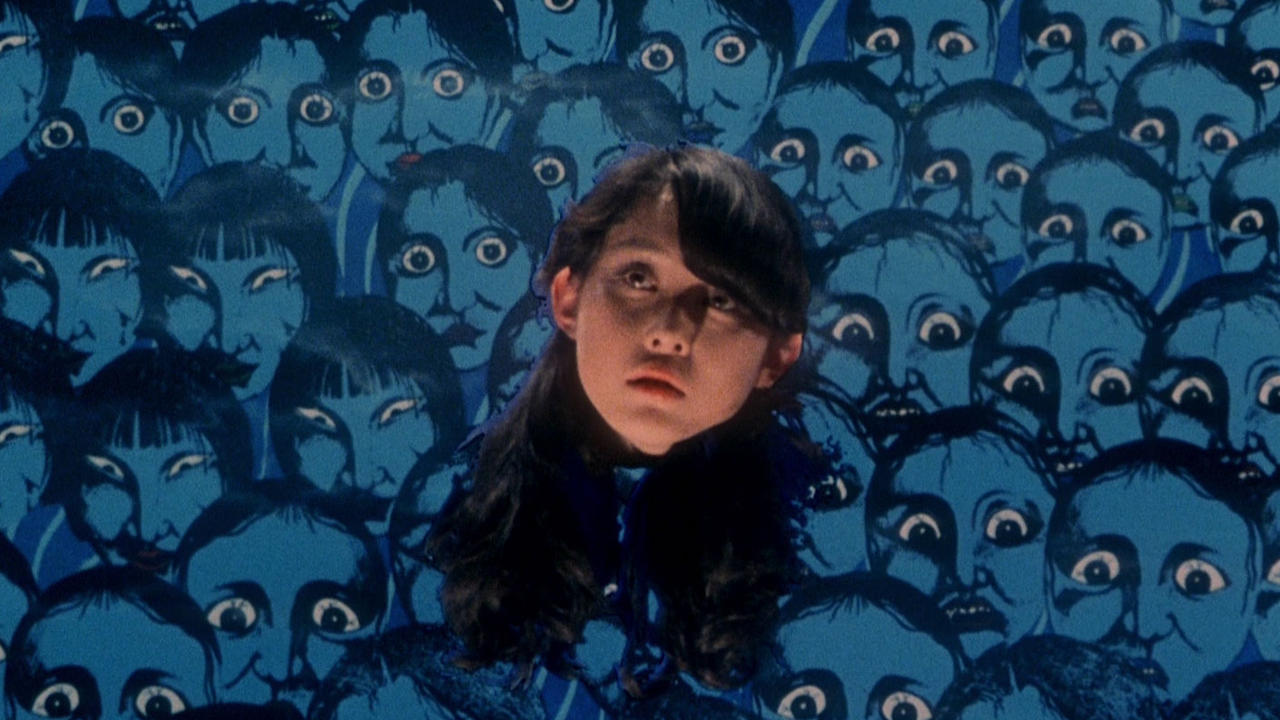

5. House by Nobuhiko Obayashi

Outlandish and absurd, Obayashi’s film exudes the childlike imagination its 10 year old co-writer brought to the project. Legendary in its creation, Obayashi’s own daughter drew pictures that highly informed the visual approach of the fantastical dream reality that is House.

Familiar in its narrative structure: a high school girl decides to seek out an aunt she has not seen since she was a baby as a result of her father marrying, after years of being a widower. The girl brings along her happy-go-lucky group of friends to stay at a house which turns out to be alive, transforming the positive dreamy stimulus of the early sections of House into an all out horror film.

Extremely fast-paced and totally visually distinct, one would be hard pressed to compare Obayashi’s overstimulating masterpiece to any other film.

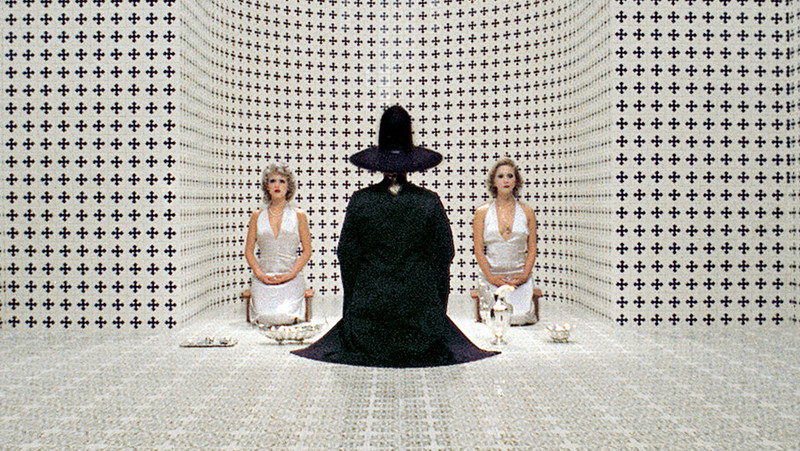

6. The Holy Mountain by Alejandro Jodorowsky

From the totally distinct surrealist mind of Alejandro Jodorowsky came his incredibly ambitious film, one that can be appreciated as a satire of human beings as a species.

The Holy Mountain is a work of continual bewilderment which follows an unnamed, Jesus-like figure called the Thief as he explores the wildly unpredictable, unimaginable world. Eventually he comes across a tower the people offer food to and grapples up its side, using a giant hook to pull him to its top. There he discovers the Alchemist, played by Jodorowsky himself. The Alchemist proceeds to teach the man how to become immortal, how to transcend his human existence.

Symbolically dense, The Holy Mountain does work as a breakdown of humanity and all its groups and religions. Shocking in its bluntly absurdist twist on what is clearly an absurd world we all live in.

7. Possession by Andrzej Zulawski

An essential film depicting the eternal conflict between Man and Woman, Zulawski’s work is one of a marriage imploding in on itself, of expanding resentments and withheld connection.

Yet to describe Possession in this fashion seems to indicate it’s similar to Kramer vs. Kramer or some other social drama about a marriage ending, of a battle over custody and care of a child. But, there is something supernaturally lascivious that manifests itself between the couple, something that transforms Zulawski’s work into a horror film vs one of cliche in divorce and courtrooms. The battles of this film are terrifying and stripped down to their bare nerves.

Distinct in its frantic visual approach composed of circling, violent camera movement to go with a piercing score that also works to cut through the senses, Possession is totally individual in its strangeness and horribly exciting approach.