Hayao Miyazaki is one of the most renowned figures in the world of anime, and animation in general. In his capacities as director, producer, scriptwriter, animator, author, manga artist, and co-owner of Studio Ghibli, he has shaped the field, as he brought anime to the attention of the world audience as something more than a genre simply targeted toward teenagers.

“Spirited Away”, his magnum opus, became the highest grossing film in the history of Japanese cinema, and was the first anime to win an Oscar. In 2014, he was awarded an Honorary Academy Award for his impact in cinema and animation, being only the second Japanese to win this award after Akira Kurosawa.

Considered one of the greatest storytellers of our time, he has been presenting titles of artistry and depth since 1972, and although he’s currently retired as a director, he remains very active in the field through Studio Ghibli.

Here are 10 of the most distinct traits of his unique style.

1. Pacifism

The belief that disputes can be peacefully resolved without the use of physical force is one of the most frequently recurring themes in Miyazaki’s works. “Castle in the Sky”, “Howl’s Moving Castle”, “Princess Mononoke”, and “Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind” are distinct samples of the fact, since the main characters strive to bring peace among worlds filled with conflict.

Although physical confrontations are also present, they are used to point out their futility, as he uses conflicts, even war, to promote peaceful resolution.

In “Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind”, as soon as the Tolmekian troops use the Giant Warrior to burn the toxic jungle, they are assaulted by thousands of Ohms that bring destruction and death upon their passing. The pacifism of the film is exemplified in the last scene, where Nausicaa is revived, giving an end to the conflict.

In “Castle in the Sky”, the violent clashes between Sheeta, Pazu, their pirate friends, and Muska and his soldiers exemplify their futility, the worthlessness in the struggle for power. The same applies to “Princess Mononoke”, with the struggle between Irontown and the forces of the forest.

In “Howl’s Moving Castle”, a film Miyazaki shot to show his distaste for the 2003 Iraq War, actually shows the idiocy of war through Madame Suliman, who has only sadistic motives to create conflict. In that fashion, he also showed that the conflicts in the modern world are instigated due to the desires of bloodthirsty people.

2. Flying scenes

Miyazaki has stated repeatedly his love for airplanes, particularly of old ones. His family owned a company that produced wingtips for Zero fighters, and that fact had a huge impact on his character. That is why every film of his contains flying scenes of some kind, as he wants to portray aviation as an object of admiration and awe. However, he has stated that he was attracted to military aircraft as a child, but he grew to detest them as he got older, since he realized their destructive power.

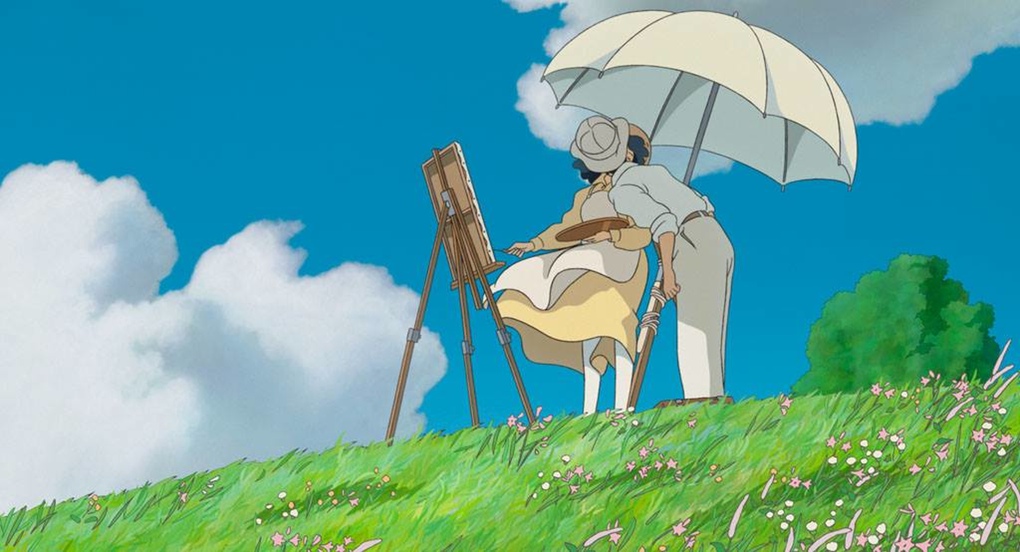

This point of self-controversy is chiefly presented in “The Wind Rises”, where Jiro Horikoshi dreams of building planes, but as he realizes the consequences warplanes can have, he feels regret for his manufacturing of death-machines.

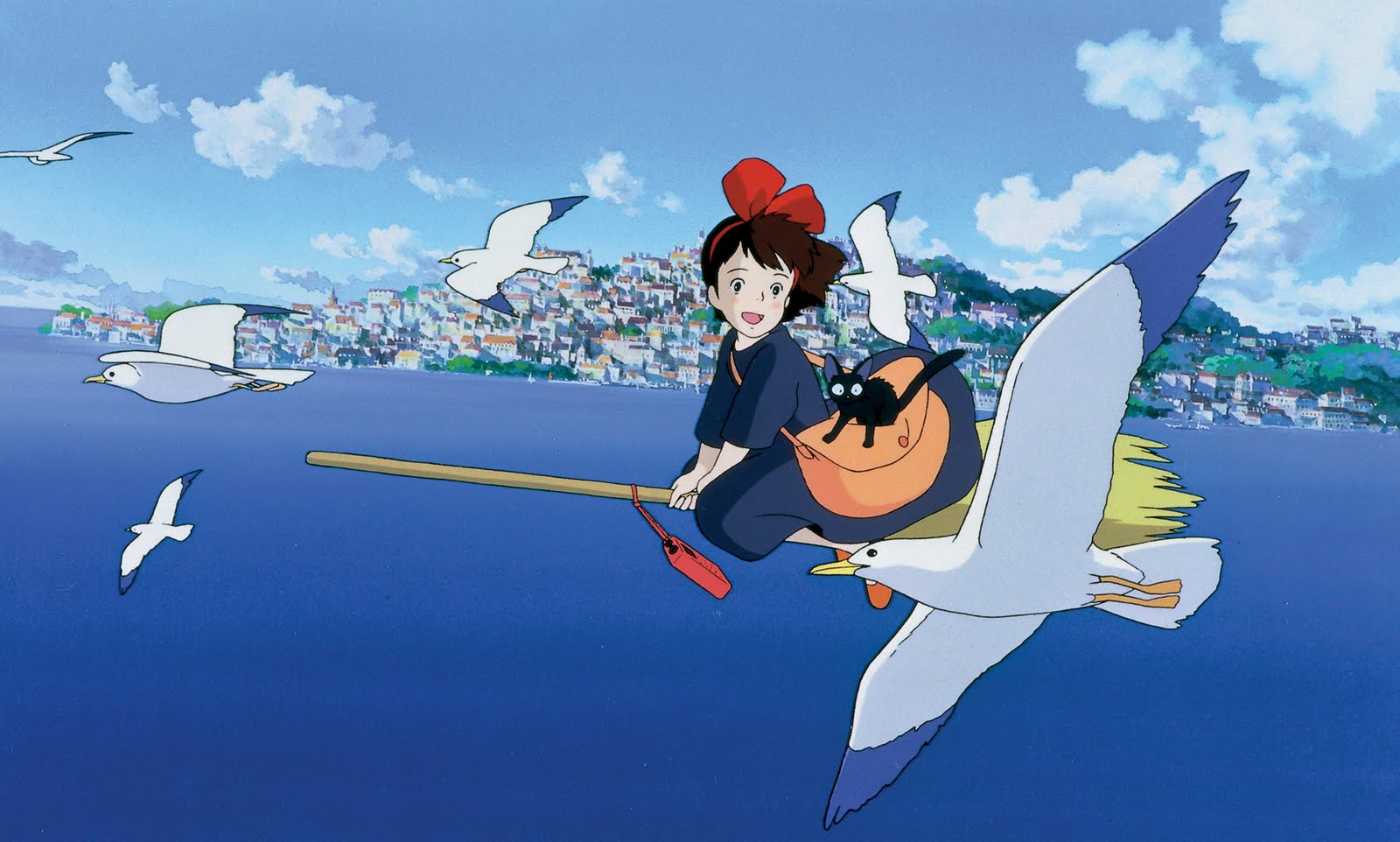

Other films centered on flying are “Porco Rosso”, where the depiction of the various aircrafts is utterly realistic, and “Howl’s Moving Castle”, where unique aircrafts are presented both as objects of beauty and destruction. In “Kiki’s Delivery Service”, Kiki is flying on a broomstick and in “My Neighbour Totoro”, the titular creature flies Satsuki and Mei through the night. Lastly, “Spirited Away” features Haku, a boy who can transform into a flying dragon, who eventually is ridden by Chihiro.

3. Female protagonists

The majority of Miyazaki’s films feature female protagonists. According to him, girls seem more gallant and the impact of their actions is larger in scenes where, for example, a girl is shooting a gun. Furthermore, he later stated in a question asking, “Why are your protagonists always female?” to which he responded, “Because I like women.”

His female characters, however, are not frail princesses like Snow White, for example, but determined and occasionally fierce individuals. This characteristic is most evident in Nausicaa from “Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind” and in San from “Princess Mononoke”. Other female characters, such as Sophie in “Howl’s Moving Castle”, Chihiro in “Spirited Away”, and Kiki in “Kiki’s Delivery Service”, are portrayed as courageous individuals, unwavering in their effort to overcome obstacles.

Furthermore, even the female villains are portrayed as complex and multidimensional characters, which in many cases are ambivalent. For example, in “Princess Mononoke”, Eboshi may be responsible for plenty of destruction, but she also saves sick women.

This trait of his also proves the evident feminism emitted from his works.

4. Environmentalism

The environment is one of the central themes in Miyazaki’s filmography, both as a physical presence and as stimulation for a number of comments.

Sometimes in his films, nature and humanity live in harmony in various settings, including the country, town, or even cities. Miyazaki thinks that people could and should live in nature or, at least, coexist in harmony. This notion becomes rather evident in “My Neighbor Totoro”, where nature seems to take care of the children.

However, Miyazaki is disillusioned about nature, since he considers it a place that also emits power, as is the case with the toxic jungle in “Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind” and the forest in “Princess Mononoke”. In both of these films, a harsh ecological message is also presented: if people decide to go against nature, she will certainly exact revenge.

5. Optimism

As Miyazaki’s films are chiefly addressed to children and young people, and since he thinks that it is important to them to have a positive view of the world and to retain hope, he induces his works with much optimism, which chiefly appears at the end of his films. “Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind”, “Princess Mononoke”, and “Spirited Away” are distinct samples of this tendency.

However, his optimism is regularly interconnected with pessimism, as in “Laputa: The Castle in the Sky”, where greed does much harm before the optimistic conclusion takes over.

According to Miyazaki, and in direct connection with his environmentalism, nature usually finds a way to restore balance with humanity.

Once more, though, Miyazaki is disillusioned about the reality, and his optimism is kind of “tempered”, since in the majority of his films, a lot of awful things also happen before the redemption offered by the ending.