We have reached the final instalment of this series, where every Academy Award winner for Best Picture is ranked within their respective decades. As we have not reached 2020 yet, all of the most recent winners will be combined with the previous decade. Why shouldn’t they be? We have witnessed a resurgence in the integrity that a Best Picture win can signify.

We get the occasional Oscar Bait win, but we also get inventive cinema (some of the most creative Best Picture winners since the ‘70s). With the inclusion of the internet and e-journalism, the Academy has shifted once more due to the change of society.

These films will barely resemble those that won in the ‘20s and ‘30s, and even the criteria for what a winner should have is drastically different (back then, films didn’t have the history of cinema to comment on or be influenced by). We’ve entered great territory within the years of both filmmaking and how filmmaking is rewarded by establishments like the Academy Awards. For one last time, here are the Best Picture winners of the new millennium (so far) ranked from worst to best.

16. Gladiator (2000)

This is one you either love or hate, and the test of time seems to make people lean towards the latter option as it falls behind the other epics of its time. Ridley Scott is a peculiar director, because he has shown signs of being a masterful filmmaker (Alien, Bladerunner) and the capacity to make appalling works as well (Robin Hood, The Counsellor, Exodus: Gods and Kings).

No matter what, he tries. While Gladiator is another effort of his in his arsenal of larger-than-life films, it certainly does not rank with his best materials, especially since his not-so-great works share more in common with it. What do you remember from Gladiator the most? The strong speeches? The intense battle sequences?

What about the glacial moments in between? Revisit the film, and you will notice the large amounts of waiting-room periods in between each and every exciting event. The build up does not pile your expectations and anticipations, rather it simply showcases what goes on behind closed doors.

Match that with an environment that is still impressive but not earth shattering (since these period sets, costumes and styles have been bested since), and you’ve got a ho-hum tale of vengeance that seems to stay still rather than fling itself forwards.

15. Crash (2005)

Crash isn’t as bad as it is made out to be, yet it is far from a Best Picture nominee, let alone a winner. Its win over Brokeback Mountain will forever rank in the upper echelons of Academy disappointment.

Unlike some other films that have caused upsets (Ordinary People, Dances with Wolves) that have been unfortunately tainted by their wins, Crash is a film that displays its problems on its own, rather than relying on the quality of the film it beat. Crash means well, with its social commentary and its wish to have political situations bubble in a festering pot. These representations are meant to depict an ongoing struggle the world faces daily. That’s fair.

Many of these tales are problematic, though. A child rushes to save her father’s life because he taught her that she has an invisible invincible shield? An abusive police officer saves the woman he sexually harassed previously? These storylines, along with the others, definitely have thought provoking and tear jerking moments, yet at the end of the day, when the film ends, what did we really get from it?

Films like Magnolia have done the society-caving-in-on-itself story better, and Crash fizzled out shortly after it made a mark on viewers temporarily. There is still a lot that can be pulled out from this film, but it will most likely remain a Best Picture winner that lacked the permanency each winner usually strives with.

14. Chicago (2002)

A film must be pretty spectacular to beat The Pianist, and Chicago does not match that expectation. Rob Marshall’s crime musical has great intentions but the resolutions fall so short that you will feel the rug ripped from beneath your feet.

The story deals with crimes, legal conundrums and slander, and yet it wraps up so safely that you may feel robbed. The film does not need to dive into dark territory necessarily, but you witness a lawyer try to get a criminal off, and you won’t feel any justice from it.

Chicago is credited for helping the resurgence of the musical film, and if that is so, then it deserves some sort of credit. Additionally, its numbers and production are both quite stellar. The colourful cast also helps to make the film a pleasant experience.

Chicago is a fun ride, but it could have benefitted from a stronger finale; it is an album in a sense that it is a collection of songs and maybe not the most complete unit. We may see a new musical take the crown of the latest to win Best Picture (with La La Land), but Chicago, for now, holds that distinction, no matter how underwhelming its payoff may be.

13. The King’s Speech (2010)

Seven years later, this year’s Best Picture winner is bound to be reevaluated. The Social Network was gearing up to sweep the Oscars, and, all of a sudden, through the magic of the Weinstein’s, The King’s Speech swooped in from out of nowhere and won. It was not a complete surprise since this film’s success slowly crept up through the awards season.

Referring back on the film now, it is still a strong effort, yet it does not quite live on as well as its contemporaries that year (127 Hours, Black Swan, Incendies, Blue Valentine, and, yes, The Social Network). Tom Hooper’s period piece is punctuated by its masterful ending speech that narrates the state of the world as everyone is at a stand still. It is exquisite, but maybe not enough to fully deserve the win.

Still, you have an exceptional cast led by Colin Firth’s tasteful performance. The monochromatic uses of greens and greys paints Britain in both a stale and a progressive light; would Britain freeze or prosper under the new king? Geoffrey Rush is a wonderful addition of comedic relief that never overstays his welcome.

The depictions of dictation and annunciation is well examined, as this is a biopic with a strong focus on a theme and narrative. Maybe The King’s Speech didn’t quite deserve its win, but it is still a fine and delightful piece of contemporary cinema.

12. A Beautiful Mind (2001)

It is now time to look at an underrated Best Picture winner; an imperfect creation that perhaps get more flack and hatred than it deserves. Does A Beautiful Mind get John Nash’s life wrong? Maybe a little bit, as many major elements are ignored (his unfaithfulness to his wife, for instance), but it may not have been wise to focus on these aspects that do not pertain to the film.

Is the representation of schizophrenia awful? It may be inaccurate (Nash only heard voices and never imagined figures), but it is a movie representation on his illness. A Beautiful Mind fixates on promoting a tale of mental sickness within the confinements of an academic institution and society, and, for what it’s worth, it does its job reasonably well.

The wonderful music (by the late James Horner) and the greatest performances of Russell Crowe’s and Jennifer Connelly’s careers help make this flawed film a tearjerker. Ron Howard’s super-Hollywood directing do make this film feel a little shoed-in, but the aim to turn this troublesome story into an emotional imprint works in its own right.

A Beautiful Mind is a rare film where the separation from the academic and empathetic perspectives may need to happen in order to best enjoy it, but it’s well worth it.

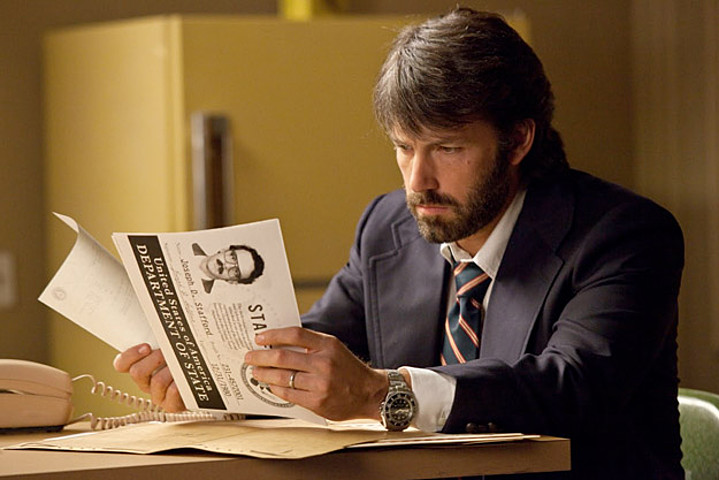

11. Argo (2012)

Ben Affleck’s third success (after Gone Baby Gone and The Town) ended up bagging him the award for Best Picture without an accompanying Director nomination. That’s a shame, because this was his biggest piece of evidence that he was a highly capable filmmaker to date.

Argo does face some unmistakably poor choices, such as the one sided perspective of the citizens of Iran (it isn’t just offensive, it’s simply substandard writing as well) and the lack of acknowledgment of Canada’s embassy amidst the rescue mission. Yes, Argo has been pegged with these missteps since it was released.

What Argo does right is channel a continued anxiety from start to finish. You are pummelled with uncomfortable shot after uncomfortable shot, and you will still feel uneasy with how it will all end despite the story being recently well known. Affleck is strong at creating tension within the construction of his films (even if this sensation is not caused by the characters), and Argo is a fine case of this talent.

There are even some humorous moments, and they are dark enough to keep the uneasiness alive. Argo may not have been the best political thriller of that year (Zero Dark Thirty sadly got overlooked for nonsensical reasons), but Argo has stayed powerful enough five years later to claim its honour.

10. Slumdog Millionaire (2008)

Here comes another film that has been heavily questioned since its win. Slumdog Millionaire will either win you over or will not live up to its hype. Before you pull out your pitchfork, a few things should be taken into account with this winner. Danny Boyle’s reinterpretation of Vikas Swarup’s novel Q & A is a wise combination of two of the biggest film industries in the world: Hollywood and Bollywood.

Slumdog is Hollywood in structure and content (the more severe moments, for instance). It is then Bollywood in aesthetic style (Dutch angles and rich colours), its focus on music (popular tracks, mind you, in an American fashion) and its romance that is passionate yet never sealed with an on screen kiss.

Who Wants to be a Millionaire was once a worldwide sensation, where many tuned in and sat glued to their televisions for an hour. This story takes every correct answer into account with the evidence of one poor man’s life and hardships to back up each guess. The final question is the resolution of a running theme throughout the film, and Jamal doesn’t know it.

It’s the Hollywood/Bollywood ending set up to have Latika come back into his life, with a voice heard around the world; pure genius. Slumdog Millionaire may not be everyone’s cup of tea, but the intellect behind each and every decision should not be ignored.

9. Million Dollar Baby (2004)

“I don’t train girls.” Clint Eastwood has been a part of the rise, fall, and revival of the Western genre, which was a style that anchored on lone male outlaws and masculine gun slingers. One of his great directorial efforts is partially centred around his refusal to coach a woman, and a sensational bond between two characters and a director and the star is formed.

It is a shame that Hilary Swank has not been featured in the roles she was once getting, as she is a phenomenal actress with the ability to replicate one soul in two drastically different conditions. She plays that off here, with the infamous twist ending that changed internet film summaries forever.

This is not an underdog story that goes as planned. It is a representation of life, where everything is the most of what you make of it. The gym the boxers practice in is run down and grimy. Every main character has identity problems and a lack of pure compassion outside of their own circuit.

This was a story that needed to be told, and its was pumped out quickly (shooting took less than a month). It is one of the last times Eastwood has stopped the world in its tracks through his filmmaking. It was through a female-centred story, a non-typical ending, a lack of powdered optimism and without any sort of sugar coating.