Stanley Kubrick’s obsessive level of detail was both a blessing and a curse, in that the films he made rank as some of the best of all time, but there are only thirteen of them. Nevertheless, his relatively scarce output has lead to a relative consistency between each film that few other directors can match.

Even from his very first feature, Fear and Desire, his auterial signatures were already in place; from his fascination with the human eye, the use of long tracking shots and one-point perspective, to seemingly hypnotic performances.

Nevertheless, despite his directorial consistency, the material he covers is vast: from Ancient Rome to 18th Century Ireland to the First World War to 1990s New York to the Vietnam war, Kubrick’s interests rarely seem to be linked. It is what he brings to his best films in terms of the direction that elevate them into the realms of greatness.

Taken together, Kubrick is a director whose work gets more rewarding with each subsequent viewing. There is not one film by Kubrick that isn’t worth watching, either for its inherent value or for how it informs his other works.

Additionally, from depicting a nuclear war as a comedy, to trivialising teen murder, to adapting a story about a pedophile, Kubrick has always been renowned as someone who likes to court controversy. Thus what better way to honour his spirit than by ranking them from worst to best? Let us know what you think in the comments.

13. Fear and Desire (1953)

Fear and Desire is an abstract experiment that although daring, nonetheless has the feeling of a pretentious student project. It was Kubrick’s first film, and he made it on a shoestring budget and with a cast and crew of less than twenty people. For some directors, when they know what story they are telling and limit themselves to an interesting location or idea, this can yield fascinating results.

Yet for Kubrick, the result here is too abstract and bizarre to make any sense or remain remotely compelling. Whilst there are some interesting scenes, such as the close-ups of the eye and the girl being tied to a tree, they aren’t tied to anything concrete to make these individual images worthwhile.

Kubrick, always the perfectionist, denounced the film himself, and tried to destroy the negatives; so its safe to say that he is also in agreement. Nonetheless, as the director’s first film it already showed his desire to tell stories differently, and in that sense remains essential viewing for any Stanley Kubrick completist.

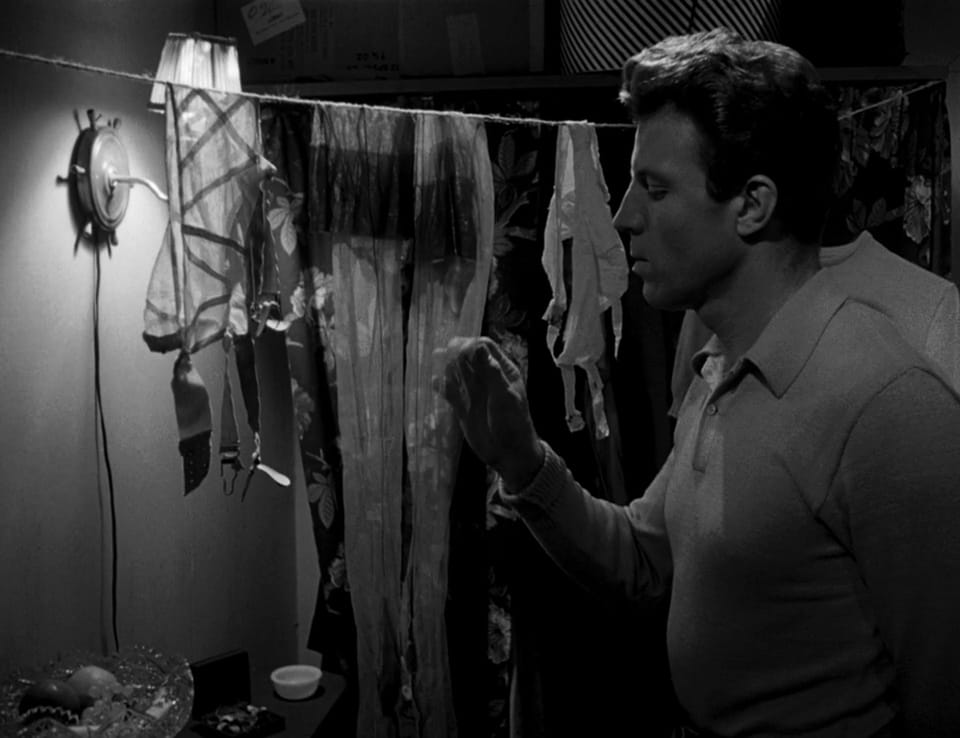

12. Lolita (1962)

Lolita’s failure cannot truly be pinned on Stanley Kubrick. Taking what is essentially an unfilmable novel — as the book relies so highly on its intricate and brilliant wordplay — it never reaches the delicious heights of Nabokov’s original vision. There is no doubt that both artists matched each other in ambition, intellect and calibre, but perhaps they were not truly suited to work together.

Whilst Kubrick was brilliant at taking mid-tier novels and spinning masterpieces out of their adaptations — no offence Stephen King and Thackery — the idea of taking one of the best novels of the twentieth century, which was so notorious because of its content, and trying to adapt it in 1962 was a noble idea that never quite worked.

The film is dull in comparison to the books constant celebration of language. The choice to shoot it in black-and-white makes little stylistic sense, Peter Sellers — who would later be so great in Dr Strangelove — doesn’t seem to know what he is doing, and many of the more daring parts of Kubrick’s vision were censored by the prudish MPAA anyway. It’s an adaptation that never quite translates the feeling of the book in cinematic terms. Nonetheless, Kubrick’s ambition is nonetheless commendable.

11. Spartacus (1960)

Spartacus is a typical film in the swords-and-sandals genre, in that it is extremely long, has epic battle scenes and it is a remarkably expensive film that represents some of the worst excesses of the Hollywood period at that time.

Additionally, it rarely feels like a film made by Stanley Kubrick. This is reflected in the production; written by the blacklisted Trumbo, the producers fired original director Anthony Mann after only a week. Kubrick was roped in to salvage the production; thus meaning that he did not have the level of artistic control he was usually privy to.

This reflects badly on the film itself, which despite having its diverting moments — the “I like oysters and snails” scene and “I am Spartacus” — never really comes alive on the screen. Instead it feels like an almighty slog.

Billed as one of the first epics to have more intellect than spectacle, it nonetheless is still an epic Hollywood movie that has dated very badly, never reaching the heights of its contemporary Ben-Hur. Thankfully for Kubrick, and the rest of the moviemaking world, he would never again relinquish any control to producers ever again.

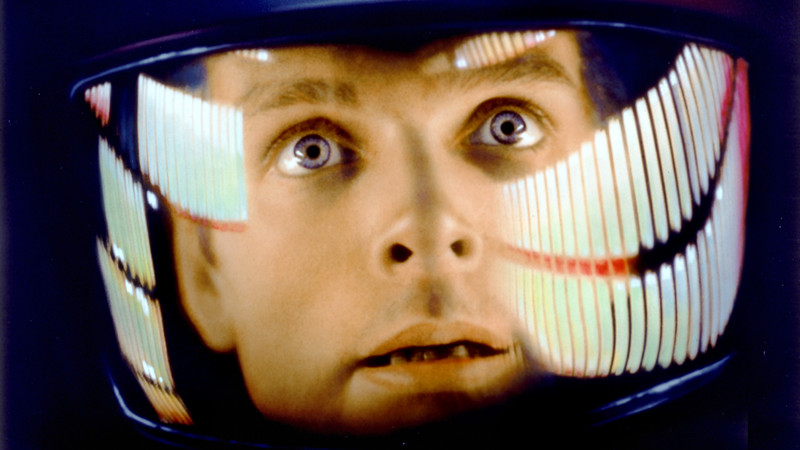

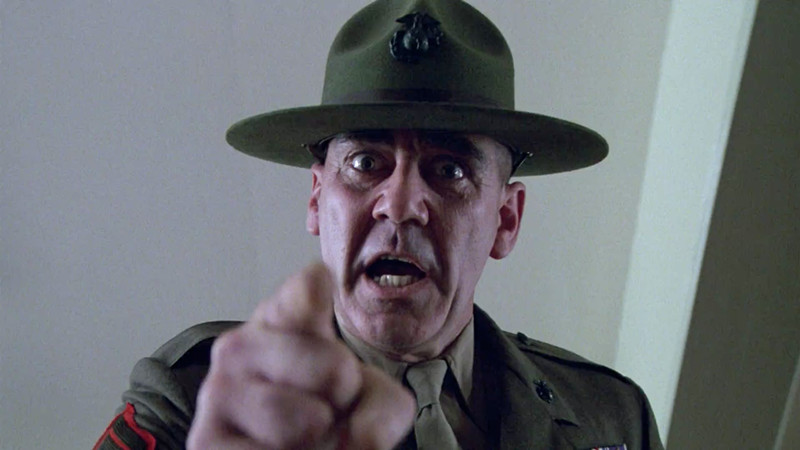

10. Full Metal Jacket (1987)

There are two films in Full Metal Jacket. One is up there with Kubrick’s best, the other is woefully flat. Judging on the first half alone, the film would be in Kubrick’s top five; the second half, somewhere just near the bottom. As a result it feels schizophrenic. Whilst the first half, depicting military brainwashing, replete with a barnstorming performance by Lee Ermy as an oppressive drill instructor, is tight and well controlled, the second is merely a series of diverting set-pieces that never really amount to anything.

Kubrick’s refusal to shoot on location affects the narrative highly. Whilst amazing Vietnam films filmed either on location or in similar climates, Kubrick rebuilt the tropical country in England. Therefore in comparison to films such as Apocalypse Now or Platoon, Full Metal Jacket can’t help but feel rather anaemic.

9. Killer’s Kiss (1955)

Killer’s Kiss is by far Kubrick’s most underrated gem. A cold slice of noir set on the heartless streets of New York, it is a tale of love and deception that is as spellbinding as it is blackly told. It is one of Kubrick’s slimmest films — coming in at only 67 minutes — yet this short length is its strength; telling a small story with the utmost economical precision.

Kubrick knew how to make more with less. Of note to aspiring filmmakers is the dialogue told by Irene Kane to Jamie Smith that we never see, but are told through voiceover. To make the scene retain interest, Stanley Kubrick shot a beautiful sequence of a woman — presumably Kane’s sister — ballet dancing. This choice of direction is an expert example of how to keep the viewer intrigued even when expositional dialogue is being doled out.

There are other striking sequences; including a fight that takes place among mannequin and boxing scenes that surely proved influential on Martin Scorsese’s Raging Bull. With only his second feature, we can see Stanley Kubrick finally coming into being as a fully-fledged auteur.

8. A Clockwork Orange (1971)

When adapting this novel by Anthony Burgess, Kubrick makes one clear change to the material that arguably makes the film superior. He changed the ending, so instead of having our protagonist redeem himself, he is let off almost scot-free from his actions. It is this lack of didacticism that has made the film so controversial, a controversy that arguably lasts until this day.

It shows violence objectively and without condemnation, almost willing us to enjoy such grotesque actions, especially when scored by classical music such as “The Thieving Magpie” and “Ode To Joy”. It is this very ambivalence that gives its film its arguable greatness. We are not sure how to react, thus having to question our very own moral position.

Other moral questions abound: the societal conditions that can give birth to such monsters (reflected by the brutalist buildings the film is shoot against), whether or not aversion therapy is the moral thing to do, and whether free will is more important than being a law-abiding citizen. Causing the most controversy of Stanley Kubrick’s career when it came out, A Clockwork Orange still manages to split the jury when it comes to debating the films merits; something which can be said to speak to the film’s strengths.