“Cronenberg is better than all the rest of us combined.”

– John Carpenter

Originally dismissed as an audacious genre director of challenging and stomach-turning horror schlock and subversion, David Cronenberg’s career has spanned some fifty odd years wherein he’s moved from the status of pariah to internationally acclaimed master

“Film for film,” writes film critic and historian J. Hoberman, “[Cronenberg] is the most audacious and challenging director in the English-speaking world.”

Born in Toronto in 1943, Cronenberg’s name, for better or for worse, is synonymous with the cinematic subgenre he virtually created, “body horror.” He also has something of a knack for making transgressive and strangely mainstream movies from novels regularly regarded as “unfilmable”––as is the case with adaptations of William S. Burroughs’ “Naked Lunch”, J.G. Ballard’s “Crash”, and Don DeLillo’s “Cosmopolis”––as well as ascribing and legitimizing auteur theory in the maple tundra of his native Canada.

The following list attempts something of a fool’s errand as ranking Cronenberg’s distinct filmography from worst to best assumes a that, well, for one, he’s made a bad film. He hasn’t. Ask any fan of the man’s troubling and eclectic work to name their favorite and you’re bound to get a different response with each fan you ask.

Eschewing only Cronenberg’s short films, here is a master filmmakers ever-evolving (and still growing) body of work. And while we may argue over the order that these pictures should go in I think we can all agree with Martin Scorsese when he said: “No one makes movies like [Cronenberg].”

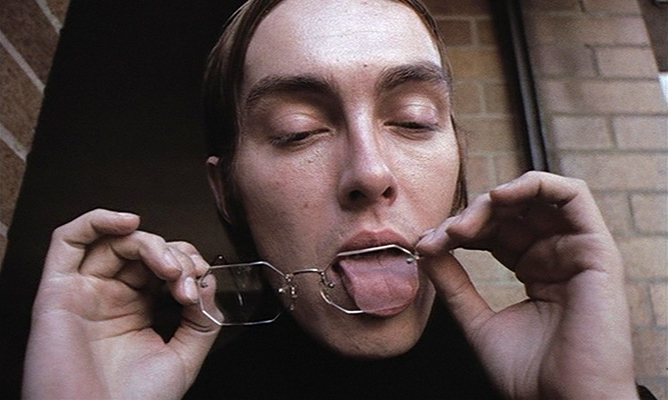

21. Stereo (1969)

Cronenberg, 26 at the time, got funding for his first feature, Stereo, by securing funding by the Canadian government under the pretense he was actually going to write a novel. The results were a somewhat amateurish experimental film which, in his own words he describes as “an investigation of the inadequacy of current sexuality.”

Part of what makes Stereo fascinating viewing is seeing all of the pet themes that Cronenberg would later become famous for; alienating technology; scabrous science; sexual ambiguity; and also the inevitable nastiness of human nature.

Darkly comic, decidedly formalized, and somewhat sterile, Stereo is set in a not too distant future and concerns seven young adults who sign up for a series of experiments for the Canadian Academy for Erotic Inquiry.

The academy, operating under parapsychologist Luther Stringfellow (Ronald Mlodzik), exploits the volunteers via a series of increasingly sinister surgeries under the guise of enhancing their telepathic potentials. Predictably, at least for Cronenberg’s fans, this leads to polymorphously perverse sexuality, drugs, and ultimately, several deaths.

The low-budget, nonprofessional actors, and non-sync sound does detract from the film, but it still has its merits.

20. Crimes of the Future (1970)

Darkly humorous and more than a little macabre, Crimes of the Future is Cronenberg’s sophomore experimental feature and a fair improvement on Stereo, which came the year before.

Once more starring Ronald Mlodzik, the film takes place in the near-future dystopia of 1997 where an epidemic called “Rouge’s Malady” has erupted via cosmetics, wiping out all sexually-mature women and mutating the remaining male populace to a regressive state. Adrian Tripod (Mlodzik) works as the director of a dermatological clinic called the House of Skin.

As with Stereo, Crimes of the Future is marred by a low budget yet it still manages a creative and very lucid visual sweep and will appeal to Cronenberg diehards who will note many of the director’s pet themes pertaining to human sexuality, kinkiness, and a decidedly sick sense of humor.

19. Fast Company (1979)

This late 1970s drag-racing drama sticks out like the proverbial sore thumb in Cronenberg’s filmography as a complete and utter anomaly. Made between Rabid and The Brood, there is a fair bit of colorful action and automobile fetishizing––Cronenberg is, after all, a regarded auto enthusiast––but it’s still a far cry from his controversial kink classic from 1996, Crash.

Detailing the comeback of ex-champ drag racer Lonnie “Lucky Man” Johnson (William Smith), as he stares down up-and-coming funny car rival Billy “The Kid” Brocker (Nicholas Campbell) and a nasty corporate sponsor, Fast Company also features the final role for B-movie queen Claudia Jennings (Deathsport, ‘Gator Bait, Sisters of Death).

Featuring far better production values than his earliest fare, Fast Company is worth checking out for Cronenberg completist, fans of Canuck cinema, and the curious, but it doesn’t add much overall to his distinct delectus, and one can’t help but feel that he was phoning most of this one in.

18. Cosmopolis (2012)

Cynically perverse and dejectedly comical, Cronenberg’s formal and high-concept take on novelist Don DeLillo’s ominous satire of the same name might be a bitter pill for some of the director’s conventional fans. Smartly casting Twilight hunk Robert Pattinson against type as Eric Packer, a twenty-eight-year-old New York billionaire with little to no scruples, his life as a privileged One Percenter is about to take a nosedive.

Largely a chamber piece unraveling in Eric’s luxurious stretch-limo soon a Picaresque procession will unravel amidst anti-capitalist protests, a presidential visit, an asymmetrical prostate, a pastry assassin, and a rather provocative tryst with art consultant Did Fanche (Juliette Binoche).

Cosmopolis provides some parallels to Cronenberg’s earlier work, namely Videodrome (1983), though it lacks that film’s fire. Still, for all the film’s staginess and parity it does surrender some edgy parody and a sharp sting.

17. M. Butterfly (1993)

In many ways this penetrating period drama, based off David Henry Hwang’s Tony Award-winning gender-twisting play of the same name––itself loosely based on actual events––is one of Cronenberg’s most underappreciated works. Jeremy Irons is French diplomat René Gallimard, assigned to Beijing, China in the 1960s where he is soon smitten by Song Liling (John Lone), a male Peking opera performer and spy for the People’s Republic of China.

An intense study on the relationship between Gallimard and Song, this tale of love, deception, transgressive sexuality is bizarre, provocative, and plays intelligently to mankind’s ability to fool itself to outstrip biological truth for love’s sake. It’s also about as understated and underrated as Cronenberg gets.

16. Scanners (1981)

In his own words a movie that is “very much about heads,” Scanners solidified Cronenberg’s burgeoning international reputation as an auteur out to literally blow minds. Equal parts horror film and sci-fi picture, Scanners stars Michael Ironside, Stephen Lack, Patrick McGoohan, and Jennifer O’Neill in a frequently goofy, strangely abstract, and visually rich conspiracy thriller about powerful telepaths (“scanners”) in the employ of ConSec, a private security firm with dubious ideas.

Cronenberg’s first fully politicized project, placing military-industrial ideas under a messy microscope, Scanners also started something of a franchise, spawning sequels and a series of spin-offs––though none of these had any involvement with Cronenberg. An essential early work, Scanners also got the Criterion treatment in 2012, much to the delight of the director’s fans.

15. Maps to the Stars (2014)

Maps to the Stars, while not explicitly a comedy, contains more humor than you’ll find in most of Cronenberg’s body of work, and that reason alone is probably what marks this satirical Tinseltown takedown the most.

Written by Bruce Wagner (Wild Palms) and buoyed by a first-rate performance from Julianne Moore as a fading two-faced starlet Havana Segrand, this film also boasts a large ensemble cast which includes John Cusack, Robert Pattinson, Mia Wasikowska, and Olivia Williams.

Amidst the satirical barbs are the expected eruptions of extreme violence—a mainspring for Cronenberg, of course—and this may be too hard-hearted for mainstream audiences. But mainstream audience expectations have never been of much concern for Cronenberg, and that may well be the point here. Maps to the Stars feels like less of an inside joke then say,

Robert Altman’s The Player, though several celebrities appear in the film as microfiche versions of themselves. This is a late-era Cronenberg picture after all; people see ghosts, mock dead children and drug addiction, all with equal impetus.