The talkies. Film remains a visual medium, but dialogue is where screenwriters flash their artistic magic on the screen. There are countless rules (more like guidelines) to writing dialogue.

It’s valuable to learn them, because great dialogue breaks a few rules, but breaks them properly. The following films have outstanding dialogue, and each one offers a unique lesson for aspiring screenwriters.

1. The Social Network (2010) – d. David Fincher, w. Aaron Sorkin

“It won’t be finished. That’s the point. The way fashion is never finished.”

This semi-fictionalized story about the founding of Facebook weaves multiple threads through a fragmented narrative structure, that jumps back and forth between Mark Zuckerberg creating Facebook and two lawsuits about the legal rights to the website that occur after its rise to the top of the social media industry.

In this masterpiece of American cinema, Aaron Sorkin’s dense dialogue stands as one of the film’s crowning achievements. The vast amount of information in this narrative, and its seamless integration into the character’s spoken words, is remarkable.

Sorkin’s “rapid fire” style of dialogue is essential to conveying the film’s narrative. “Rapid fire” doesn’t mean the characters are just speaking quickly. It refers to rapid rate at which the characters reveal narrative information. This style is on display during the film’s iconic opening scene.

The first few lines of dialogue between Mark and his girlfriend, Erica, plays as a voice over, before the film’s opening image appears on screen.

The film’s heavy, quick dialogue is thrown at the audience before the story starts its visual tack. “Did you know there are more people with genius IQ’s living in China than there are people of any kind living in the United States?” with the first line, the audience learns that Mark has an obsession with elitism. Sorkin encodes bits of information, such as that, with subtext throughout the entire film.

Another tactic the opening scene employs to draw the audience in, is placing the characters’ focus on different points in the timeline of the conversation. Mark will say something and while Erica is responding Mark jumps to his next topic without letting her finish a response. And even once Erica catches up with Mark, he jumps back to something he said earlier.

By implementing two separate timelines in the conversation, (as he does in the film’s plot) Aaron Sorkin is bringing the story and characters to life at a rollercoaster of a rate. This forces the audience pay close attention to the conversation.

Film dialogue pulls a story forward by divulging information to the audience. There are few films that use a more sophisticated way of unveiling its plot, characters, and themes, with dialogue, than The Social Network.

2. Midnight in Paris (2011) – w.,d. Woody Allen

“You’ll never write well if you fear dying.”

Writers could study the dialogue in Midnight in Paris for Woody Allen’s intellectualized wit. They could study it for the strikingly appropriate voices Woody writes for the historical figures in the film. They could study it for the way dialogue establishes Paris as the film’s setting. They would all be valid reasons to study the film’s dialogue, but the best lesson a writer can learn from this film comes from the writing advice given by the Earnest Hemingway character.

His dialogue is a hilarious imitation of Hemingway’s declarative, direct prose. With that directness he gives Gil Pender, a screenwriter, concise, clear, and essential truths on what a writer must do, and what a writer must be.

“Writers are competitive. If you’re a writer **slams fist** declare yourself the best writer.” Now, Hemingway had a particular intensity and bravado when it came to writing. Aspiring writers don’t have to match his intensity, but the fact remains that if you are a writer, striving for anything short of excellence is a waste of your and the audience’s time.

Hemingway’s sentiments on subject matter are invaluable. “No subject is terrible if the story is true, if the prose is clean and honest, and if it affirms courage and grace under pressure.” Okay, screenwriters don’t write prose, but they intend to create a story with cinema the same way prose does with literature. Stories expose truths. If a writer writes a high concept script just to write an enticing concept, the story won’t achieve any depth. And when a writer writes a script it must have clean and vivid writing.

Take it from Woody Allen’s projection of Earnest Hemingway. The two of them are not only great American writers. They are all-time great writers of dialogue.

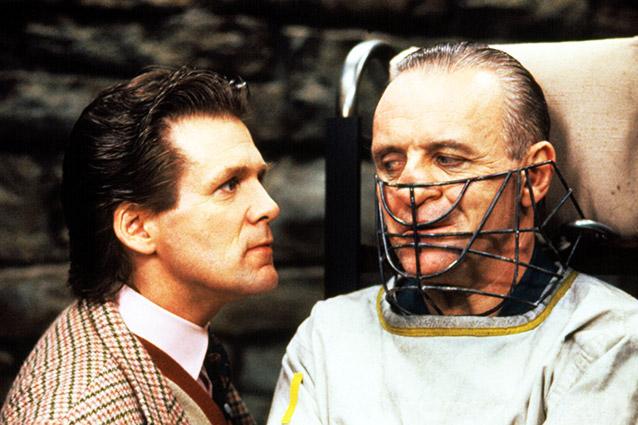

3. The Silence of the Lambs (1991) – d. Jonathan Demme, w. Ted Tally

“They don’t have a name for what he is.”

This thriller has two bone chilling villains, each one a serial killer. One is trying to help FBI Trainee, Clairice Starling, capture the other. Buffalo Bill, the transsexual killer who is making a bodysuit from the skin of his victims, and Hannibal Lecter, a psychopathic, former psychiatrist, cannibal, are two of the most blood-curdling in all of cinema. Hannibal Lecter’s dimensionality arises from the multiple archetypes he occupies in the film.

Hannibal is a villain that is not an antagonist. He is the wise old man serving as the advisor, and surrogate father figure for the protagonist, Clairice. But any serial killer is villainous regardless of their role in a film. His dialogue reflects the multidimensionality of his character. He is a genius psychopath that worked as a psychiatrist before he was locked away. Combine that genius with the monstrous nature of his character, and the audience is left with a villain who is as articulate as he is terrifying.

The most impressive dialogue in the script is n the final scene that Hannibal and Clairice speak face to face. Hannibal has the voice of the wise old man, father figure, and villain archetype.

“What does he do this man you seek?”

“He kills women.”

“No. That is incidental. What is the first and principal thing he does? What needs does he serve by killing?”

“Anger, um, social acceptance, and uh, sexual frustration, sir…”

“No! He covets. That is his nature. And how do we begin to covet? Make an effort. Answer now.”

“No, we just…”

“No. We begin by coveting what we see every day. Don’t you feel eyes moving on your body, Clairice? And don’t your eyes seek out things you want?”

In that exchange, Hannibal guides Clairice to conclusions about Buffalo Bill. He questions her the way a psychiatrist would. In this instance, that is not only the voice of a former therapist. It is the voice of a sociopath playing mind manipulation games.

At the end of the scene he speaks to Clairice as her twisted father figure, by connecting her past trauma of trying to save a lamb from slaughter with her mission of finding Buffalo Bill. “Brave Clairice. You will let me know when those lambs stop screaming, won’t you?”

4. The Princess Bride (1987) – d. Rob Reiner, w. William Goldman

“When I was your age television was called books.”

William Goldman’s The Princess Bride, based on his book, is a postmodern fairytale-comedy that is an ode to the magic of books. A grandfather reading the story to his sick grandson frames the film’s fairy tale plotline about Westley, a pirate who has returned to rescue his beloved Princess Buttercup from marrying an evil king.

The grandson, who is apprehensive to listen to the story at the beginning, grows more intrigued by the book as the film progresses. The film is as much about the enchantment of being whisked away by a good story as it is about rescuing a princess in a fairytale land. Aspiring writers could study the film for its self-reflexive depiction of storytelling alone.

The Princess Bride also serves as a great lesson on the way dialogue establishes the tone and genre of a film. Fairytales are traditionally dramatic epics, many of which are dark in tone. The Princess bride is a comedic fairytale, and the dialogue of it establishes its humor.

There are many witty and memorable quotes throughout the film. The scenes where a masked Westley is chasing Buttercup’s kidnappers are some of the funniest and most well written of any in the film.

From Vizzini, Inigo, and Fezzik watching Westley climb the cliffs:

“He didn’t fall? Inconceivable!”

“You keep using that word — I do not think it means what you think it means.”

To Westley’s interaction with Inigo:

“I could do that. But I do not think that you will accept my help, since I am only waiting around to kill you.”

“That does put a damper on our relationship.”

And Westley’s battle of wits with Vizzini:

“Not remotely. Because iocane comes from Australia, as everyone knows. And Australia is entirely peopled with criminals. And criminals are used to having people not trust them, as you are not trusted by me. So I can clearly not choose the wine in front of you.”

“Truly, you have a dizzying intellect.”

The entire sequence is comedic gold. The comedic tone is established earlier in the movie, and the three confrontations with the kidnappers, each of which is resolved in a humorous way, continues that tone.

5. The Godfather (1972) – d. Francis Ford Coppola, w. Mario Puzo and Francis Ford Coppola

“I believe in America. America has made my fortune.”

There is a reason why The Godfather has left such an imprint on American culture. Its themes are established and woven through the narrative of the film masterfully. Any screenwriter can look to The Godfather when studying theme, and in particular, how to use dialogue to establish theme. Theme is the central topics that unify all the elements of a film. Mario Puzo and Francis Ford Coppola establish the film’s themes with dialogue in the opening scenes.

The central topics on which the film comments are introduced, through dialogue, during the opening sequence while Vito Corleone entertains his guests’ requests on his daughter’s wedding day. The first line Vito speaks touches on the theme of crime. His colleague, Bonasera, tells Vito that his daughter was beaten and raped by her boyfriend.

Bonasera is distraught that involving the police only resulted in the attackers receiving a suspended three-year sentence. Vito’s immediate response to Bonasera’s gruesome and shocking monologue is “why did you go to the police? Why didn’t you come to me first?”

With his first spoken words the audience knows that Vito is a powerful man who operates outside the law. By suggesting that Bonasera should have sought his help before he contacted the police, Vito indicates his distrust for American law enforcement, a sentiment shared by many American immigrants of the early 20th century. It is the oppression that Vito faced as an immigrant that forced him to turn to organized crime to build his fortune in America.

Vito’s position as the Don of an organized crime family is secondary to his role as the patriarch of his own family. His family is his source of masculinity. Themes of masculinity and patriarchy are also established during his daughter’s wedding. While entertaining the request of his godson, Johnny Fontaine, Vito asks him if he spends time with his family.

When Johnny says that he does, Vito replies with, “Good. ‘Cause a man who doesn’t spend time with his family can never be a real man.” Lines that establish, and comment on themes are abundant during the film’s exposition, and creates the ideologies of the film that have given The Godfather its lasting legacy.