Alongside the likes of Garrone, Moretti and Guadagnino, Paolo Sorrentino is one of the Italian filmmakers with most magnitude in the industry today. In terms of style, Sorrentino’s films are known for being intellectually cold, darkly satirical, and overflowing with sensual and vibrant imagery, altogether for which he is referred to as the modern Fellini. Since his film debut, Sorrentino’s quality in craftsmanship and style as an auteur has remained unscathed.

The writer and director of the now critically acclaimed series The Young Pope, made his feature film debut back in 2001 with the loosely veridical drama film One Man Up, which opened to formidable reviews in the 58th Venice International Film Festival.

Following One Man Up, Sorrentino delivered mafia thriller The Consequences of Love (2004) and drama The Family Friend (2006), the former of which has gathered a cult following since then. It was not until 2008 that Sorrentino’s international breakthrough arrived in the form of Il Divo, a biographical political satire that won the Jury Prize at the Cannes Film Festival.

In 2011, Sorrentino made his first splash in American cinema though This Must Be the Place, starring Sean Penn, the Italian director’s first English spoken film as well as a hidden gem in his filmography. During the 2013 Academy Awards season, Sorrentino won the Best Foreign Language Film award for The Great Beauty, a film whose large thematic scope encompasses themes of disenchantment, human frailty and a country’s malaise. Since then, the Italian auteur delivered Youth (2015), a film of similar themes to The Great Beauty, but intended for an American audience.

Sorrentino is frequently compared to Fellini given their similar style and themes in common, of which stand out the following: (1) imagery that is both surreal and sensually stimulant, (2) the subversion of authority, organized institutions and moral values through satire, (3) eccentric characters with odd peculiarities as well as existential ennui, (4) the addition and development of new characters, oftentimes resulting in narrative digressions, in order to expand thematic dichotomies and juxtapositions.

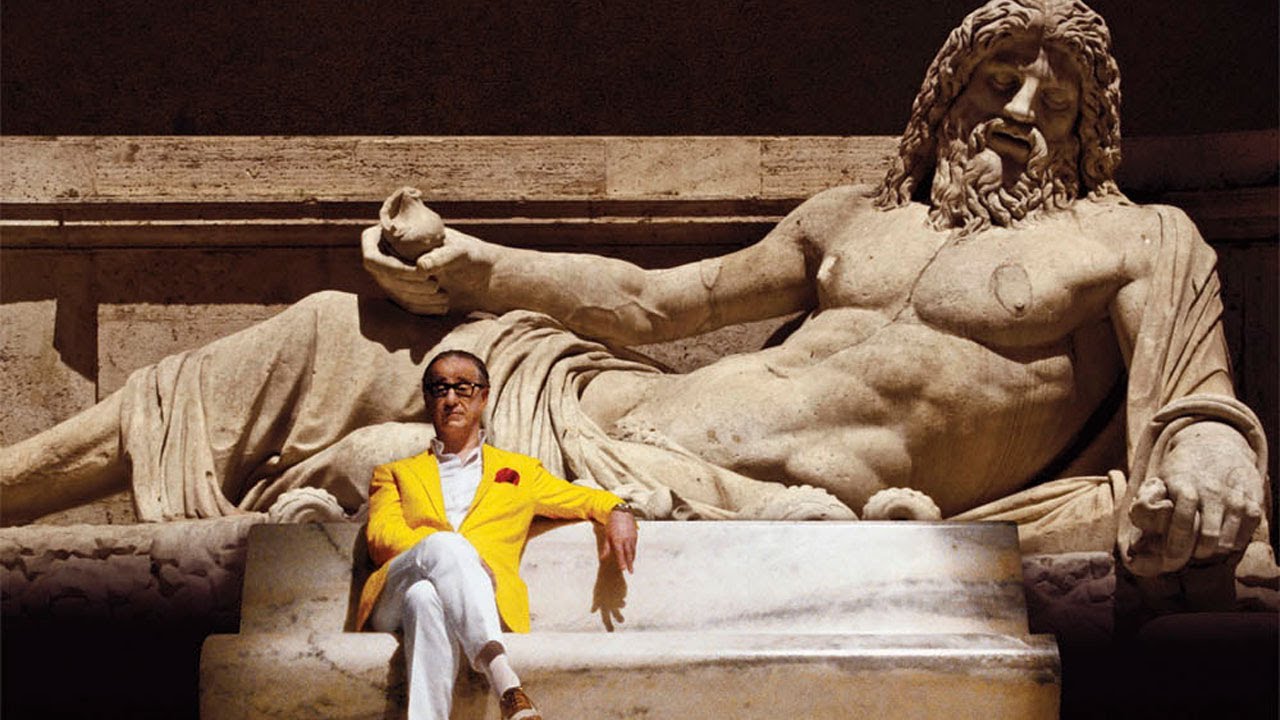

Although all the aforementioned motifs overarch his oeuvre, perhaps Sorrentino’s most distinguishing Felliniesque feature is his instinctive ability to visualize his films through the eye of a painter – vibrantly colorful, enriched in contrasts, thematically abstracted, and endowed by a notion of immediacy – while simultaneously perceiving and constructing the narrative through the pen of a novelist.

Given Sorrentino’s commitment to both high quality and unconventional stylized films, for purposes of the ranking order, this list will prioritize the Italian director’s implementation and development of the thematic and technical features that distinguish Sorrentino as an auteur.

Therefore, although this discussion will indeed account for essential cinematic elements such as narrative structure, it will take keener observation on thematic and stylistic growth of the Italian filmmaker’s sociopolitical statements and universal concerns regarding human nature. Altogether, this list does not intent to strike a definitive rank as much as it aims to provide a discussion, a brief overview of the thematic, stylist and technical qualities that give Sorrentino’s films their identity and stylistic flair. Enjoy.

7. This Must Be the Place (2011)

Soul searching. ‘80s rock ‘n’ roll. Deadpan humor and a lot of cosmetic make-up. There is a particular charm and awkwardness to This Must Be the Place that clouds judgment to determine whether the film is Sorrentino’s weakest or is one of his most misunderstood and underrated works.

This road movie stars Sean Penn as a retired rock star that despite leading a seemingly tranquil life along his wife, a firefighter (Frances McDormand), he still maintains the same outfit and cosmetic prowess from back in his rock ‘n’ roll days, and altogether lives sheltered inside the comforts of retirement.

Penn delivers both a hilarious and iconic performance as Cheyenne, who is at most times a deadpan comedian, and during his most quiet moments, subtle and sympathetic in conveying his grievances without falling in caricature hijinks. In terms of music, former Talking Heads member David Byrne does an excellent job in bringing to life the film’s premise by complementing its protagonist’s Gothic aesthetics as well as echoing ‘80s New Wave aesthetics throughout Cheyenne’s road trip.

Cinematographer and Sorrentino’s longtime collaborator, Luca Bigazzi indulges both the notion of wonder in the outside world and cosmetic glamour in TMBtP’s commonplace scenery through saturated, vibrant colors, and otherworldly Impressionistic dawns and dusks

However, TMBtP is not as successful in delivering its material with the same conviction and composure as Sorrentino’s other films. Instead, Cheyenne’s soul searching frequently unfolds as flimsy sequence of episodes that oftentimes lacks direction.

Cheyenne’s intentions for finding the former Nazi, Tony’s disappearance, and McDormand’s discovery of a child resting on the porch of her house, are but a few of the incidents and motives why This Must Be the Place fails to justify and/or support throughout its running time.

Nonetheless, This Must Be the Place has a strangely alluring quality to its design, almost experimental in its dissonance between being the soul searching of a Wim Wenders inspired road movie and the seriousness of a story about Holocaust horrors. Similar to its ending scene, This Must Be the Place is forcibly enigmatic, oftentimes confusing and bland, yet it is emotionally provocative, charming, and never predictable.

6. One Man Up (L’uomo in più , 2001)

What Sorrentino’s film debut One Man Up may lack in scale, it compensates through its engaging and compelling character study. Set in ‘80s Naples, One Man Up centers on the juxtaposition of two men’s lives, both initially at the prime of their careers until they are cast aside by society and are forced to come to terms with unfortunate circumstances.

The first collaboration of what would flourish to become an amazing actor-director partnership, Toni Servillo succeeds in delivering an eccentric, lascivious, but sympathetic performance as the cocaine fueled club singer as well as a foil to Andrea Renzi’s taciturn, passive, and also sympathetic football coach.

The narrative pace in One Man Up may be slow enough to demand patience from viewers, but Sorrentino’s writing provides plenty of black comedy and unpredictable circumstances to maintain an amusing tone throughout the film.

By this point Sorrentino had not yet developed or allowed himself to experiment fully with the abstract and hyper-stylized designs of imagery and accumulative storytelling he would then adapt fully to achieve a distinctive coherence in his later films (The Consequences of Love, Youth).

Therefore, there are several instances in One Man Up, such as the ending in which the two men’s lives coincide, that its dissonance between the preservation of coherence and the director’s artistic motivations result in the loss of credibility and the undercut of its dramatic impact.

Nonetheless, the heavy sociopolitical statements about Italian morality, the intricacies of both the rejection and support of art, and the decadence of virtues, stand among the motifs and themes Sorrentino successfully introduced, grasped and questioned in One Man Up before expanding throughout his oeuvre.

5. The Family Friend (L’amico di famiglia, 2006)

Repulsive. Greedy. Misogynistic. Salacious and overly solicitous, The Family Friend follows the titular individual, Geremia de Geremei (Giacomo Rizzo), a moneylender and loan shark who is obsessed with money and frequently insinuates himself on other people’s affairs for his own personal gain.

Rizzo delivers one of the best performances of the year (2006) as the covetous, yet eccentric and magnetic Geremia whose drive to use his power to make others suffer for his own self-loathing leads to unfortunate events.

If his previous films (One Man Up, The Consequences of Love) were known for inspirations in Antonioni, The Family Friend marks the first film in which the dominating influence is Fellini. Most notably, the surreal and sensual visions that plague Geremia’s surroundings, such as the volleyball players slowly goggled by the camera, the three centurions as well as the iconic and ethereal visual compositions.

Also, this Felliniesque notion of the carnivalesque is present in the classicist and grandiose architecture, that doubles as a satirical symbol for the hypocrisy behind order, as well as the accumulation of character perspectives, due to the wider array of characters, which works for both of film’s strengths and weaknesses.

Sorrentino’s digression from the straightforward story is a recurrent habit in other of his films (The Great Beauty, Youth), and in the best of cases, expands The Family Friend’s juxtapositions regarding sardonic criticism towards morality and order. However, there are instances in which the deviations add little to the central character’s development.

Additionally, similar to One Man Up, Sorrentino’s insistence of music under pretexts of dramatic enhancement oftentimes undermines the capacity for immersion, if not the dramatic force of some of its scenes.

Alongside Andreotti and Titta from Il Divo and The Consequences of Love respectively, Rizzo’s performance as The Family Friend’s sardonic protagonist is among the best of Sorrentino’s creations. Altogether, Bigazzi’s colorful compositions and cityscapes, Sorrentino’s skill to pen witty remarks and exchanges, and the half-cruelty, half-truth behind the protagonist’s motivations, make The Family Friend a deeply compelling film.