Creating something as complex as a conscious being is the most vital task in writing a script. Characters are the human representation in an art that comments on humanity.

Every last character has a desire, and that desire drives every aspect of the story. Through their desire, a character changes from the start to the finish of the story. A writer must create characters that have desires and conflicts he or she cares about care about if they have any chance at making their audience care.

1. Toy Story 3 (2010) – d. Lee Unkrich, w. Michael Arndt

Make the audience care. The only way stories impact people is if the audience cares about the characters.

Toy Story 3 is a tearjerker because the audience came to know Andy’s toys for over a decade. Lead by Sherriff Woody, the zany cast of toys overcame conflicts in two separate movies by the time we reconvene with them for Pixar’s third installment of the series. Most screenwriters don’t have the luxury of inheriting fully developed characters, but Toy Story 3 proves that putting characters through peril creates emotional investment in those characters.

In the Toy Story series, the conflict of the first two films centered around Andy’s close-knit group of toys rescuing each other from the clutches of a toy-sadist. The third film deals with the same separation anxiety between the characters.

After being accidently donated to Sunnyside Daycare, the group of toys decides to stay in their newfound paradise of constant playtime. Woody, however, escapes the daycare to go into storage and fulfill his purpose of always being there for Andy. But when woody learns that a tyrannical teddy bear is running the toy’s social structure over at Sunnyside, the movie turns into another rescue mission.

After rescuing his friends from the peril in Sunnyside Daycare, Woody and the rest of Andy’s toys get caught in a dump truck that drops them onto a conveyor belt that leads to an incinerator.

Once again, the characters have to pull themselves out of despair. As they near the burning pit that the garbage on the conveyor belt is funneling into their deaths appear imminent, and Woody, Buzz, Slinky Dog, Rex, Hamm, Mr. Potato Head, Mrs. Potato Head, Jessie, and Bullseye all join hands and accept their fate as they descend toward the fire.

The audience is suspended in dismay as they watch the toys they’ve come to know, the toys who escaped a sadistic neighbor’s house in the knick of time to make the move to their new house, the toys who rescued each other from a grubby toy collector, and the toys who just escaped a totalitarian teddy bear, descend toward a fiery death. And in the knick of time, again, a giant claw operated by their (toy) alien friends, lifts the toys out of the funnel of death.

On top of the funny quirks each toy possesses, their sharp one-liners, and their charisma, the audience connects with these characters because they’ve seen them weave their way in and out of trouble over and over again. Toy Story 3 is an emotional rollercoaster because the audience cares, deeply, about these silly little toys.

2. The Shawshank Redemption (1994) – w.,d. Frank Darabont

You need one character. One character, with one goal, and that character will be your protagonist. And the whole movie will revolve around that one character trying to reach that one goal. Some more daring screenwriters use more than one, though. Frank Darabont wrote The Shawshank Redemption using two protagonists.

It’s unclear that there are two protagonists at the start. It appears that Andy Dufresne, a wrongfully convicted banker, is the central character of the story. Ellis “Red” Redding seems to be no more than the film’s narrator, who becomes Andy’s best friend while they’re both locked away.

The first three acts focus on Andy’s stay in Shawshank. During that time he builds a library, helps his fellow inmates get their high school equivalency diploma, and even helps the guards with their taxes every year. His motives are unclear at the time, but a conversation with Red reveals that his acts of kindness are his way of redeeming himself for any mistake he has made. Andy’s story comes to a close at the end of act three, when he escapes from Shawshank.

In the fourth act (The Shawshank Redemption breaks a lot of rules of conventional screenwriting) Red becomes the protagonist. With Andy gone, the film focuses on Red’s transformation in regards to hisstance on hope. Earlier in the film Red claims, “Hope can be a dangerous thing.” He was locked away in a maximum-security prison for decades, and any fire that resembled hope inside him burned out while he was locked in there.

After being released from prison, while he has a crisis over whether or not he can readapt to the world outside of Shawshank, Red finds a note from Andy inviting him to come live in the small village of Zihuatanejo, Mexico. In his letter, Andy says, “hope is a good thing, maybe the best of things, and no good thing ever dies.” The last words of Red’s voice over narration are, “I hope.” The movie ends with Red reuniting with Andy on a beach in Zihuatanejo. A beaming smile is spread across his face.

Both protagonists have separate goals and character arcs. They both transform from the beginning to the end of the script, but they do so at different paces and at different times throughout the movie. Both arcs are interconnected. Andy’s redemption changes Red’s attitude about hope.

The two both overcame the demons that haunted them in Shawshank, but they were two different demons. Andy’s was dealing with the gross injustice of staying in prison for twenty years for a crime he never committed. Red’s is his lack of hope of ever living a life outside of Shawshank. The two character arcs rise and fall apart from each other, and because of each other.

3. Little Miss Sunshine (2006) – d. Jonathan Dayton and Valerie Faris, w. Michael Arndt

A script with an ensemble cast focuses on a group of characters with equal weight in the narrative. Little Miss Sunshine has one of the most fleshed out ensembles of any American film in recent memory. There are six characters in the ensemble, and each character, along with their respective desire, is introduced during the film’s exposition.

First we see Olive, a young girl, with the images of a Miss America pageant on an old television reflected on her glasses. Her desire is to compete in beauty pageants. The reflection of The Miss America pageant on the lenses indicates her desire.

Then we see Richard Hoover (think about a certain nickname for Richard, and the function of a Hoover vacuum) giving a motivational speech at a community college. Richard is in the midst of finalizing a book deal about his 9 step program “Refuse to Lose.”

Next we’re introduced to Dwayne, a gangly teenager, lifting weights and crossing off a day on his calendar in his room. It is soon learned that Dwayne has taken a vow of silence until he becomes a test pilot for The Air Force.

Next we see Ed Hoover, Richard’s father, snorting a line of heroin. He just wants to do heroin, but he’s also helping Olive with her pageantry.

Then we’re introduced to Sheryl, Richard’s stressed out wife, smoking a cigarette. Her only desire in the film is to be a good Mom.

She is driving to pick up Frank, her brother, from the hospital, after he just attempted suicide. It is later learned that his suicide attempt stemmed from break up, followed by his ex-lover’s new boyfriend getting a MacArthur Genius Grant for studying the philosophy of Marcel Proust (a distinction that Frank believes he deserves).

At the start, this dysfunctional family consists of six individuals living in the same house, but in separate worlds. The film is about these characters coming together during a road trip to Olive’s to a beauty pageant.

There are two distinct moments that signify this family’s unification. The first is when they are forced to push their Volkswagen Microbus to start it. With no other options, because of a blown out clutch and the family’s financial issues, the Microbus needs to be pushed by hand to fifteen miles per hour to get it up to third gear. The family is forced to work together. After an intense and funny sequence, where each member of the family pushes the van and jumps into the moving vehicle through its sliding door, they cheer as a group, and laugh at the absurdity of their shared triumph.

The other moment occurs at the end of the film, when Olive is performing at The Little Miss Sunshine Pageant. She is performing an obscene dance, set to Rick James’ Super Freak, that resembles a stripper’s dance routine. While the pageant organizers are begging Richard to stop his daughter’s performance, the rest of the family jumps on stage and dances with Olive to mock this event that hyper-sexualizes preteen girls.

An ensemble cast consists of separate characters, but the characters are individual parts of one entity. The character arc of Little Miss Sunshine is that of the family as opposed to that of the individual characters.

The film starts with this dysfunctional family living in their own separate lives with their own separate desires. They’re all forced to unite under the same objective of getting Olive to her beauty pageant. By the end of their wacky road trip, each member of the family has the exact same objective of sticking it to the snooty, image-obsessed freaks at the beauty pageant. Olive, that little ray of sunshine, brings her family closer.

4. Good Will Hunting (1997) – d. Gus Van Sandt, w. Matt Damon and Ben Affleck

Character archetypes are a screenwriter’s friend. All writers must strive for originality, but an archetype is useful in determining a character’s purpose in a script. Matt Damon and Ben Affleck’s character driven drama, Good Will Hunting, has a stunning example of the mentor archetype in Sean Maguire.

Will Hunting is a boy-genius, from Boston’s Southie neighborhood, that would rather spend his time drinking with his buddies than tap into his enormous potential. He is bailed out of his latest brush with the law by an M.I.T. mathematics professor, Gerald Lambeau, who has taken note of his genius. One stipulation of Will’s parole is to see a therapist. That is how Will, the prodigy, meets his mentor, Sean.

A mentor must be able to address the specific challenges their prodigy presents. In Good Will Hunting, Sean’s competence is evident when comparing him to the first two therapists Will visits. Reluctant to the idea of therapy, Will tries his hardest to be a disengaged patient by calling the first therapist gay and mocking the hypnosis the second therapist tries to perform. Will tries to break Sean in their first session by disrespecting Sean’s dead wife.

Sean grabs Will by the throat and slams him against the wall. Will’s cocky demeanor washes away as he realizes that Sean won’t play his mind games. Sean is the first therapist that broke down the wall Will builds in his relationships.

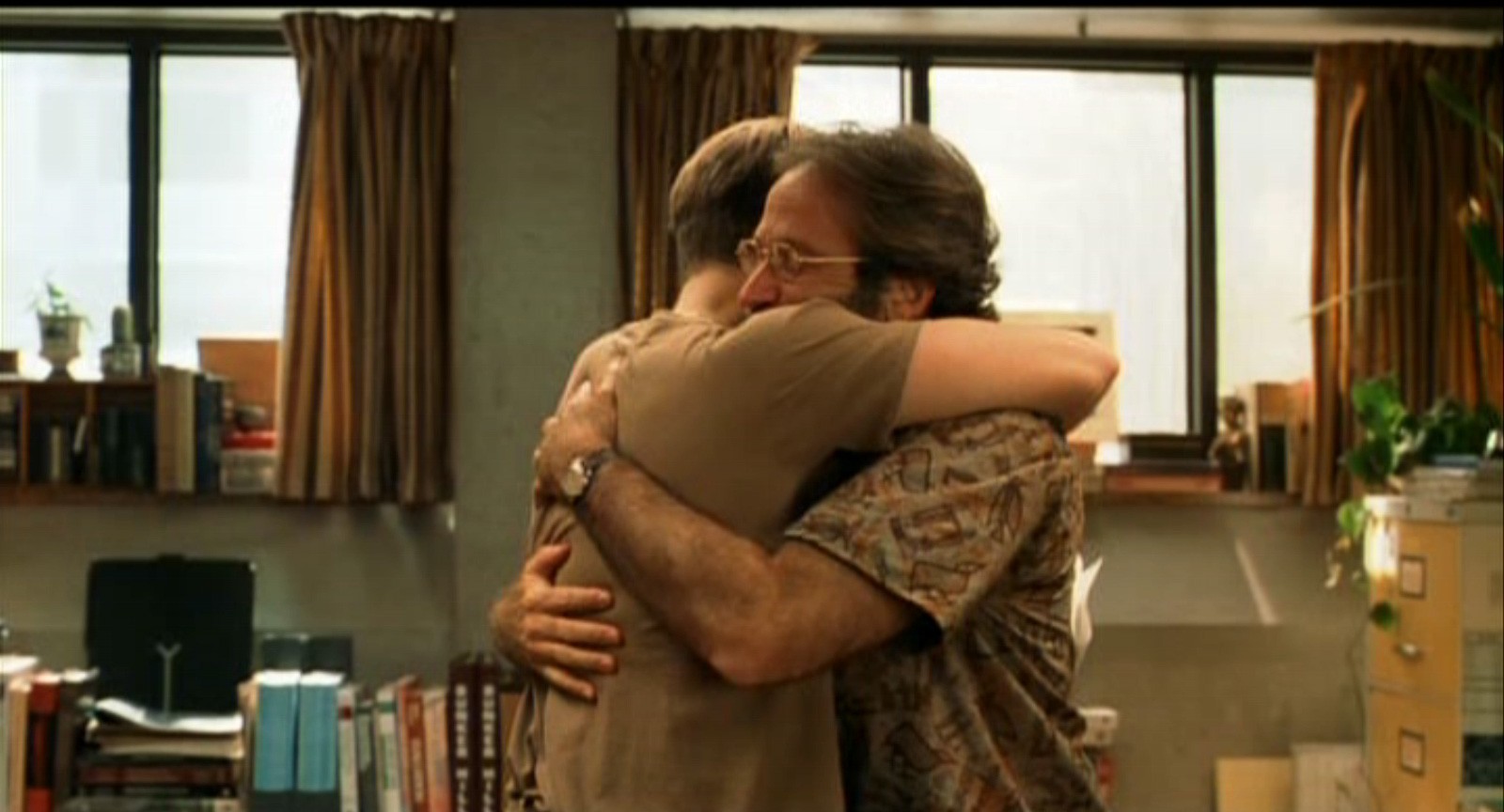

In their third session, Sean encourages Will to pursue a relationship with his newfound love interest, Skylar. Sean can see that Will’s unwillingness to use his genius potential stems from his past traumas, the first being his parents giving him up at birth, the second being the physical abuse he suffered as a foster child. Whereas Gerald and the other therapists were concerned with motivating Will to pursue a career that will utilize his genius, Sean knows that solving Will’s fear of abandonment and intimacy is the key to unlocking his potential.

That is how Sean’s character achieves a dynamic relationship with his prodigy. He knows how to address his true needs. That is made apparent at the end of Will and Sean’s last session, when Will cries hysterically after Sean repeatedly reminds him that the abuse he suffered as a child was not his fault. And Sean’s efforts in mentoring Will come to fruition in the final scene, when he receives a note from Will telling Sean that he’s going to California to “see about a girl.” The last shot of Sean shows him smiling, knowing that Will has overcome his fear of intimacy.