Many (including those who make comments on this list) note that the world “masterpiece” gets thrown around an awful lot (awful being the key word) these days. One big danger of using words too often is that they end up losing their impact.

Too often in the modern world, things (events, people, entities, etc.) end up having to be exaggerated in order to make the subject of the exaggeration look worthy of consideration. The sad thing is that this usually sets up that subject to look like a disappointment and often makes what virtues that person, place, thing, etc. possesses look small indeed.

The following 10 pictures may or may not be masterpieces depending on one’s point of view. Several of them are the works of “auteurs”. These aren’t the pictures that might come immediately to mind when the name of their maker comes up. Some are their maker’s one big hit. Just because someone only managed one hit doesn’t mean that hit isn’t good (and that’s one more than many manage to achieve).

In going over this list, the reader is asked to consider these films on their own merits. Might another film as good or better be on this list? Perhaps so, but that doesn’t mean that these 10 aren’t deserving of their place here as well.

1. Bigger Than Life (1956)

For many years all one had to do was mention the name of Nicholas Ray to anyone who knew even a little bit about film and the response would be, “Oh, the Rebel Without a Cause guy!” If the respondent was of a certain age and/or had first encountered that 1955 film at a certain age, the next words would be something like “Gosh, I love that movie!” (Though that usually had something to do with star James Dean as much as that cinematic ode to the mixed-up and misunderstood teen-agers of the world.)

Well, that film is proof that big ones can kill you. Ray received his only Oscar nomination (for writing the film’s script) and was elevated to big time director after the better part of a decade in film (he and close friend, the great director Elia Kazan, started around the same time and would both have a really active decade and a half in films, sporadically putting out films thereafter).

However, his personal style and the corporate attitude toward making films that prevailed in the big Hollywood studios during the 1950s were at odds with one another. Ray had begun his career at the then-ailing RKO studios, where the chaotic atmosphere and lack of strong leadership actually worked in his favor.

After “Rebel” (his only film at dictatorial Warner Brothers, despite its profitable status), Ray bounced around from studio to studio. Between “Rebel” and the day Ray walked off the set of 1963’s “55 Days at Peking” (effectively ending his career with that lavish independent production) he made nine films.

None were great hits, though some look quite fine today (1957’s excellent “Bitter Victory”, now finally restored to his cut; 1958’s “Party Girl”, showing that Rebel’s superb mastery of color and widescreen imagery was no fluke; and 1961’s “King of Kings”, quite moving if one puts aside preconceived notions and looks past enforced box office compromises). He worked for up and coming Columbia Pictures, a declining MGM, and independent producers but also found a fertile ground for a while in the always youth oriented Twentieth Century Fox soundstages.

Oddly enough, his best film there wasn’t 1957’s “The True Story of Jesse James”, a wide and colorful look at the outlaw and his family as a bunch of misjudged kids, but instead, a rare Ray film which looked at adults and very adult problems. This is 1956’s “Bigger Than Life”. This film examines a problem which wouldn’t seem strange or obscure at all to modern sensibilities but was most unusual at the time.

The story concerns Ed Avery (the formidable James Mason, also a producer on the film, giving one of his best performances), who is a school teacher and family man (to wife Lou, played by lovely and talented Barbara Rush and son Ritchie, the fine child actor Christopher Olsen). Times are lean in the Avery household (though it looks awfully luscious by current standards) and Ed is moonlighting as a taxi dispatcher.

All the family needs is for him to get sick but that’s what happens and it’s not just a small illness. Ed turns out to be fatally ill with an illness of the arteries and the doctors tell him the only real chance to stay alive is to take the then experimental drug cortisone.

As with many drugs discovered during World War II or stemming from the research done during the war, the medical profession was basically looking only at the drug’s beneficial properties and marginalizing the side effects. In this case, the consequences are frightful indeed as Ed, freed largely from his pain, also takes leave of his senses, becoming a deeply scary household demigod, ever more controlling of his family until he quite seriously tries to kill them.

This sort of thing just wasn’t talked about in the 50s, which deeply believed in better living through modern science. Also, Ray and his writers don’t cheat or insult viewers. Though the worst is avoided, the film is quite open-ended. The bedrock problems have not and cannot be solved (despite a warm last shot, Ed is still probably going to be dead soon).

In addition to the actors playing the family, the film also gave an early chance to Walter Matthau, who’s good as the family friend (and a character many think to be a non-stereotypical, coded gay one). Though this is a small scale and intimate film, Ray still packs it with marvelous widescreen compositions and an uncanny sense of color usage. This non-crowd pleaser was, not surprisingly, not a box office hit and was rather hard to see for years, not for any legal reason but for lack of reputation.

Even worse, most of its subsequent showings were in the earlier days of TV, in badly panned and scanned, often black and white prints (killing most of the dramatic effect completely). Happily, modern technology and modern film studies have began to bring this one back in the last couple of decades. Those giving this and other Ray films a chance may find that he was way more than the Rebel man.

2. Sawdust and Tinsel (1953)

For many film fans the world over, writer-director Ingmar Bergman’s fabled career started with the one-two-three, Cannes winning/exposed punch of “Smiles of a Summer Night” (1955) and “The Seventh Seal” and “Wild Strawberries” (both 1956 and what a year!). However, in his native Sweden, much of Scandinavia and parts of continental Europe, he had been known for much of the near-decade he had begun working in films.

In the decades since, dedicated Bergman fans sought out his early films in addition to keeping up with the new films he released for so many years. Many feel, with some justification, that a lot (quite a lot) of those early films, which were surely the work of the same later and more mature artist, lack the brilliance he acquired with the years and which uplifts so many of his films from being mundane melodramas to the heights of great art.

Well… maybe so, but how many artists emerge fully formed from youth? Some of those early films are pretty drab but there are others which point the way to Bergman’s ultimate destination. Chief among these early films would have to be “Sawdust and Tinsel”.

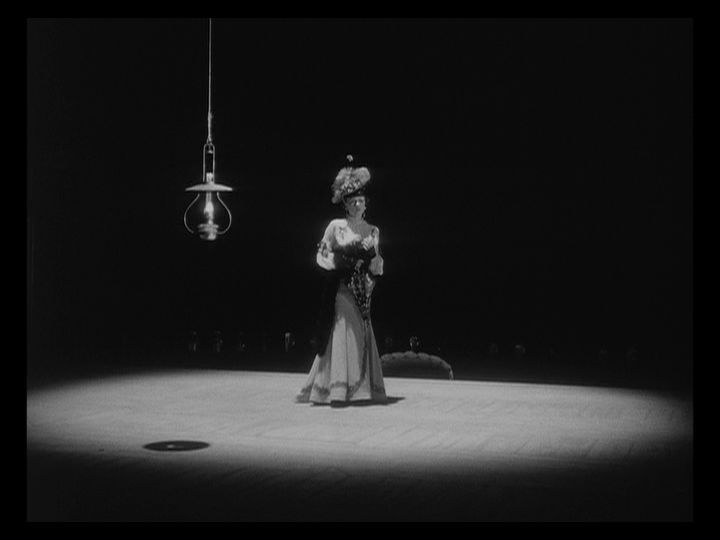

This study of human relationships caught in destructive patterns and set largely against a circus backdrop just missed the Bergman glory era by virtue of coming out in 1953. However, a number of Bergman hallmarks are already evident here. The circus setting is very much of a piece with the many theatrical motifs and performers used as locations and characters scattered throughout his works.

The story, set in rural Sweden at the beginning of the 20th century, concerns the circus ringmaster, Albert (Ake Gronberg), a married man with two sons, long estranged from his wife, Agda (Annika Tretow) who, among other things, refuses to make a life on the road part of her life. To compensate, Albert has long been cohabitating with the much younger Anne (early Bergman muse and regular Harriett Anderson, no relation to the excellent Bibi Anderson, who joined the Bergman troupe soon thereafter), a performer in the circus. Anne knows all about Agda and, as it turns out, Agda knows all about her as well.

When the circus company visits the town where Agda and the boys live, Albert and Anne go into town to obtain new costumes and props from an upscale supplier, only to be humiliated by the business’ manager (Bergman regular Gunnar Bjornstrand, in an early appearance). This prompts Albert, almost as an afterthought, to visit his family.

Anne had previously fended off the lecherous advances of roué Frans (Hasse Ekman) but now jealously decides to give in to them, especially due to the lure of a promised diamond necklace. The upshot is much, much misery and humiliation. It becomes clear that there will be no divorces, no marriages, no romantic elopements and that only the unscrupulous Frans will complete anything successfully. After all is said and done, the characters will have to continue as is, only now with the added burdens of their wrongheaded choices.

These dark currents are quite typical of Bergman, as anyone who has seen many of his films can attest. This one, however, shows the beginnings of a surreal style that heightens the drama. The most vivid example is that of a story told to Albert near the beginning of the film concerning a clown whose wife ends up disgracing both of them in front of a regiment of soldiers.

This mini-film is shot in an expressionistic style differing from that of the main body of the film and is quite striking. “Sawdust and Tinsel” enjoyed something of a vogue in the late 60s and early 70s, when Bergman’s reputation was at its peak and there were things such as actual art houses around. Sadly, it seemed to get lost in the shuffle again when the video/streaming revolution came along and many more early Bergman films were made available outside of Scandinavia. This early preview of things yet to come is still a film worth seeking out.

3. Cul-de-Sac (1966)

Roman Polanski, one of the world’s great filmmakers no matter what one may think of him as a human being, has had an up-and-down career for many pressing reasons, but his beginnings in film were as meteoric as anyone’s in film history. After a handful of noted short films (and one could do much worse than to seek out the 1958 short “Two Men and a Wardrobe”) he made his feature debut with one of the great first films ever, 1962’s “Knife in the Water”.

This would be his only feature in his native Poland, as he defected soon thereafter. He initially went to England and instantly hit pay dirt with 1965’s “Repulsion”, still considered one of the cinema’s creepiest and most adroit thrillers and one which has lost nothing with age. That film starred the luminous Catherine Deneuve, downplaying her glamour. It can’t be any real coincidence that he next film would star her ill-fated sister, Francoise Dorleac, also so beautiful and somewhat warmer than her sibling, though warmth would have little to do with the finished product.

Filmed in deliberately clammy black and white, “Cul-de-Sac” (significantly, a term for a self-enclosed dead end) is set on a remote island off an obscure section of the British coast during what looks like a barren off-season.

At the beginning, a car bearing an odd cargo of humans, gangsters Dickey (long blacklisted American character actor Lionel Stander) and Albie (Jack MacGowran), just manages to navigate a flooding causeway to get to the mostly deserted resort island. Both men have been wounded, Albie fatally.

Dickey decides that he will make the island his hideout while he awaits instructions from a mysterious superior. The inhabitants of the island are the couple who run the one hotel (an ancient, crumbling castle) on the island.

To call this pair mismatched would be a great understatement. The wife, Teresa (Miss Dorleac), is lovely, lively and quite faithless. But who can blame her? The husband, George (British character actor Donald Pleasence, now best remembered as the somewhat nutty psychiatrist in the 1976 horror classic “Halloween”), is much older but also… greatly in touch with his feminine side. In fact, he loves to dress in his wife’s clothing and use her makeup!

This basic situation might well lend itself to one of those films where innocent people are held hostage by ruthless criminals until they bravely find a way out. This is not that film. The interaction of these rather original characters is pure Polanski: nightmarish and peculiar in a constricted and suffocating way. Polanski has always had trouble getting a wide audience to accept his quite unusual (and quite dark) sense of humor.

Through his big dramatic hits such as 1968’s horror classic “Rosemary’s Baby” and the 1974 mystery-drama milestone “Chinatown” have (darkly) funny undercurrents, his deliberate comic films, such as another horror comic, 1967’s “The Fearless Vampire Killers” and 1986’s “Pirates”, baffled audiences more than anything else.

“Cul-de-Sac”, which does have a cult following, has come closer than any other mostly comic Polanski film in connecting with the public, but even it lives in the shadows of its immediate predecessors in Polanski’s cannon and “Rosemary”, which came shortly thereafter. It is like none of his other films but a unique entity of it’s own. Taken for what it is, it is a most intriguing experience.

4. The Killing of a Chinese Bookie (1976)

There might be a good case for almost every film of indie legend John Cassavetes being an underrated effort that deserves better. Yes, many film students know of his truly groundbreaking filmmaking debut, 1961’s “Shadows”, and his even bigger breakthrough, 1968’s “Faces” (and there can be no doubt that these are true indie productions, with “Faces” largely filmed in the home of Cassavetes and leading lady/wife Gena Rowlands). He and Rowlands would also have a relative box office success with 1974’s “A Woman Under the Influence”.

However, more critics and film historians seem to have seen them than film fans and every time Cassavetes looked to be about ready to breakthrough commercially, his independent instincts just had to kick in. Faces netted him an invite from Columbia Pictures to film “Husbands” in 1970 and the studio (and the audiences) didn’t know what hit them.

“A Woman Under the Influence” seemed to promise an easier time in the indie realm but it didn’t work out that way, either. Maybe the touch of success caused the filmmaker to expect better, but when his next two films after “Woman” didn’t immediately get the acclaim and audience response for which he obviously hoped, he pulled both after only about a week of exhibition each and it would be years before either was seen again (certainly in their original forms).

The later of the two, “Opening Night” from 1977, eventually was seen (mostly on cable and video) in its intended original form and turned out to be quite good. The earlier film of the two, “The Killing of a Chinese Bookie”, had a much more circuitous route.

The film centers on Cosmo (Ben Gazzara, an excellent method actor and good friend of Cassavetes), who is the owner of a rather seedy cabaret and also a compulsive gambler of impressive intensity who always gets back in deep trouble after digging himself out of equally deep gambling debts.

As the film opens, he manages to get himself into the mother of all debt situations, owning a huge amount of money to some pretty dangerous mob figures. He can’t pay the money but he might just be able to do the job the mob guys will take in lieu of it: committing the title crime against the title character (they don’t know that he’s a combat vet more than able to take care of himself in a fight). Nothing is ever clear cut in the world of Cassavetes’ cinema and neither the crime nor its aftermath goes in any way as the main character (or the viewer) expects.

“Bookie” opened at a running time of 135 minutes and, after it was withdrawn at the end of a disastrous week, Gazzara persuaded the writer-director that a big problem with the film was that it was too long (and none of Cassavetes’ films ever feel rushed for time). So, Cassavetes withdrew the film and, when it was seen again many months later, it was 105 minutes. However, this was not just a cut down version of the original but a reworking.

In later years, both versions have found their partisans (and, thankfully, the Criterion Collection in the US has made both readily available). Oddly enough, one of the film’s prime virtues may have helped caused its initial failure. Gazzara gives a fine performance and he, like the filmmaker’s other great actor friend, Peter Falk, had some great cinematic moments. His 1958 film debut was in “The Strange One” (recreating his celebrated stage performance), the first picture with an all-method cast, and he had a memorable supporting turn in 1959’s big hit “Anatomy of a Murder”, and a superb starring turn in director Peter Bogdanovich’s underrated “Saint Jack” in 1979.

However, despite his many film roles (often supporting as the year went by), he found his main success on stage and in television (and he was considered award-worthy in both mediums). Somehow, despite all of that, he never quite connected with film audiences.

He also worked with Cassavetes in “Husbands” and “Opening Night”, so all of his films with Cassavetes had troubled openings. Maybe it was the (bad) luck of the draw or the fact that sometimes good work just doesn’t go rewarded. Maybe that could be the epitaph for the career of this filmmaker (and many others).

5. Quadrophenia (1979)

The world of cinema seems as though it can encompass the entire world as it’s known but that’s a bit deceptive. The sports world only seems to work on film intermittently. Films about the fine arts are usually only for specialized audiences. And the world of rock music is usually quite dicey to put on film.

The reason is often that the audiences for these other forms of entertainment have different expectations from their experiences with such modes of expression than a cinematic one might have. No matter how skillful a concert film may be (and there have been some fine ones) it can never quite capture the feel of a live concert. Too often rock acts and stars are slotted into silly or cardboard plots calling for acting skills those performers often aren’t trained to carry out.

The British rock band The Who seemed to fare better than almost any other rock act in their ventures into film (not many, admittedly). Their classic rock opera “Tommy” was made into an over-the-top film typical of its director Ken Russell in 1975 and was a big hit (with audiences a bit more than critics, though it had its partisans there as well).

The year 1979, though, saw them hit the cinematic jackpot. The wonderful retrospective documentary “The Kids Are Alright” (still one of the best of its subgenre) was a great and lasting souvenir of their careers (and with the death of member Keith Moon shortly thereafter, a good summing up of their time together).

Just as good was a film which would not, unlike the other two, feature the members onscreen (lead Roger Daltrey, then starting a film career, played the lead in “Tommy” with the others in supporting roles) but would use the music of one of their best albums (maybe the best) to haunting and memorable effect.

The psychiatric term quadrophenia refers to a fragmenting of the mental process which results in extreme and erratic behavior. The Who had concocted another rock opera around their album “Quadrophenia” but director and co-writer Franc Roddam came up with a memorable alternate plot line for the film version (partly with the help of The Who’s greatest artist, Pete Townsend).

The film would tell the story of a seminal moment in British teenage history, namely the 1964 clash on the beach of the British resort town of Brighton between the “mods” and the “rockers”, two youthful groups who violently disagreed over style (yes, style was that important to them in that volatile moment in time). The main character, Jimmy (the fine young actor Phil Daniels), is a mod stuck in one dreary world in a bleak section of London with little to look forward to or up to. He will get swept away in the unfolding events and have a moment of high exhilaration… and then a disillusioning comedown.

This is a rare film that treats the emotional crises of adolescent years, when things often seem much larger than they really are, with due seriousness (neither too much nor little) and decency, a trick not easily accomplished.

The score, which obviously was not written especially for the film, comments on the action and interacts with it to an uncanny degree. Much of this is thanks to Roddam’s sensitivity and gift for evoking the right “feel” to this film (its emotional texture is overwhelming). He gets not only a fine performance from Daniels but the entire youthful cast (including another rock star starting a film career, Sting, striking in a mostly visual role with a lot of screen time but only one line of dialog).

How and why did this film get somewhat lost? Well, its somber nature may well have alienated its initial youthful audience (and how many of them could have related if they had given it a chance).

It also doesn’t help that no one before or behind the camera, save for Sting (who later starred in Roddam’s “The Bride” in 1985, to a lesser effect for all), went on to anything even closely as good (Roddam and Daniels mostly have worked in TV, with Roddam going into the reality realm). Well, so this was a one off. That doesn’t mean it’s minor. Even a broken clock is right twice a day and this film was made during one of those moments.