There is a scene early in “Blade Runner 2049,” Denis Villeneuve’s hypnotic and heart-bursting sequel to Ridley Scott’s 1982 future-shock detective movie “Blade Runner,” where two men crash through a wall. One is the bulbous Sapper Morton (Dave Bautista), who is one of many humanoid robots known as replicants, and the other is the slender, trench-coat-wearing assassin known simply as K (Ryan Gosling), who the LAPD dispatches to “retire” (i.e. kill) rogue replicants.

It’s grisly work (the swift, savage scuffle between Sapper and K ends with an eyeball being washed in a sink) made all the more nauseating by the fact that K is a replicant himself. Designed by the wan industrialist Niander Wallace (Jared Leto), he has been programmed to obey—even if that means, as Sapper puts it, killing his “own kind.”

Once he has completed his murderous task, K is free to climb into his flying Peugeot and soar home to his sterile apartment in Los Angeles. But then he spots something. Beneath a pale, leafless tree lies a cluster of small yellow flowers. Plucked from the ground, they have nothing left to do but shrivel. Yet K slips them into a plastic bag before heading home.

Can you blame him? Like Scott’s film, Villeneuve’s unfurls in a misery-laden future where pollution has eclipsed sunlight, ceaseless rain and corporate greed pummel crowded streets, and police officers like K, known as blade runners, have normalized state-sanctioned murder. No wonder K wants to find and preserve something beautiful; in this ghastly, failed state, it’s just about the only rebellion he’s capable of.

At times, beauty has been a problem for Villeneuve. His first English-language U.S. release, “Prisoners” (2013), received effusive reviews from critics like The New Yorker’s David Denby, who dubbed it “a thriller that digs into the dark cellars of American paranoia and aggression.” Yet the film was so joyless and brutal (remember its awful images of Paul Dano’s mutilated skin?) that watching it less like moviegoing than self-flagellation. Villeneuve certainly dug into those cellars, but they revealed less about American aggression and paranoia than they did about his own sinister imagination.

Yet the opposite was true of “Arrival,” Villeneuve’s Oscar-winning science-fiction film from last year. Shadowy, moody, and steeped in slow-churning terror, that movie wrung plenty of chills from its eerie premise (an egg-like alien spacecraft hovers above a field in Montana; a linguist, played by Amy Adams, is tasked with translating the language spoken by the squid-like beings inside). But it also swelled with crescendos of compassion as Adams extended a hand into the unknown, daring to believe that the menacing creatures before her might have something to offer humanity.

That same impassioned idealism courses through “Blade Runner 2049” (which is based on characters from Philip K. Dick’s novel “Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?”). The movie may be packed with horrors—from a sweatshop filled with child workers to a hand being squeezed against shattered glass—but there is so much more. Bravery. Kindness. Sacrifice. Love. These forces light up the film as much as the gleaming 3D advertisements for Sony and Coca-Cola that illuminate Villeneuve’s Ridley-ized L.A.—and they’re some of the many reasons why the sequel, in some ways, transcends Scott’s original.

Here are five more.

1. K and Joi’s relationship deepens the series’ meditation on artificial intelligence

“Fuck off, skinjob.” That crude insult is hurled at K by a fellow cop as he walks down the halls of LAPD headquarters. It’s a jolting jibe that alerts you that while K is surely one of the handsomest and best-dressed dystopian investigators (if there’s any movie that can turn men onto fur collars, it’s this one), he is also a pariah—which makes him different from Rick Deckard (Harrison Ford), the blade-running antihero of Scott’s film.

Deckard spent much of “Blade Runner” in isolation, whether he was moping around his cluttered apartment or scouring the streets of Los Angeles for replicants. In that respect, he was much like K. Yet Deckard also grew unsure whether he was man or machine, whereas K understands he’s a human-shaped facsimile from the start and longs to be more.

You might think that superficially, K’s certainty would simplify the sequel (the original “Blade Runner” argued that the line between the real and the synthetic is porous; how fitting that its hero blurred that boundary). But K’s desperation to be human (like the Tin Man in “The Wizard of Oz,” he doesn’t feel complete without a “real” heart) injects “Blade Runner 2049” with painful yet joyous feeling—especially in the midst of K’s strange but sweet romance with his holographic girlfriend, Joi (Ana de Armas).

K’s existence is peppered with reminders that he’s little more than a walking-and-talking weapon. As he ascends the stairs to his apartment, a woman calls him a “tinplate soldier” and even his superior officer, Lieutenant Joshi (Robin Wright, smoldering with icy wit), damns him with faint praise be declaring that sometimes, she’s forgets he isn’t human (gee, thanks).

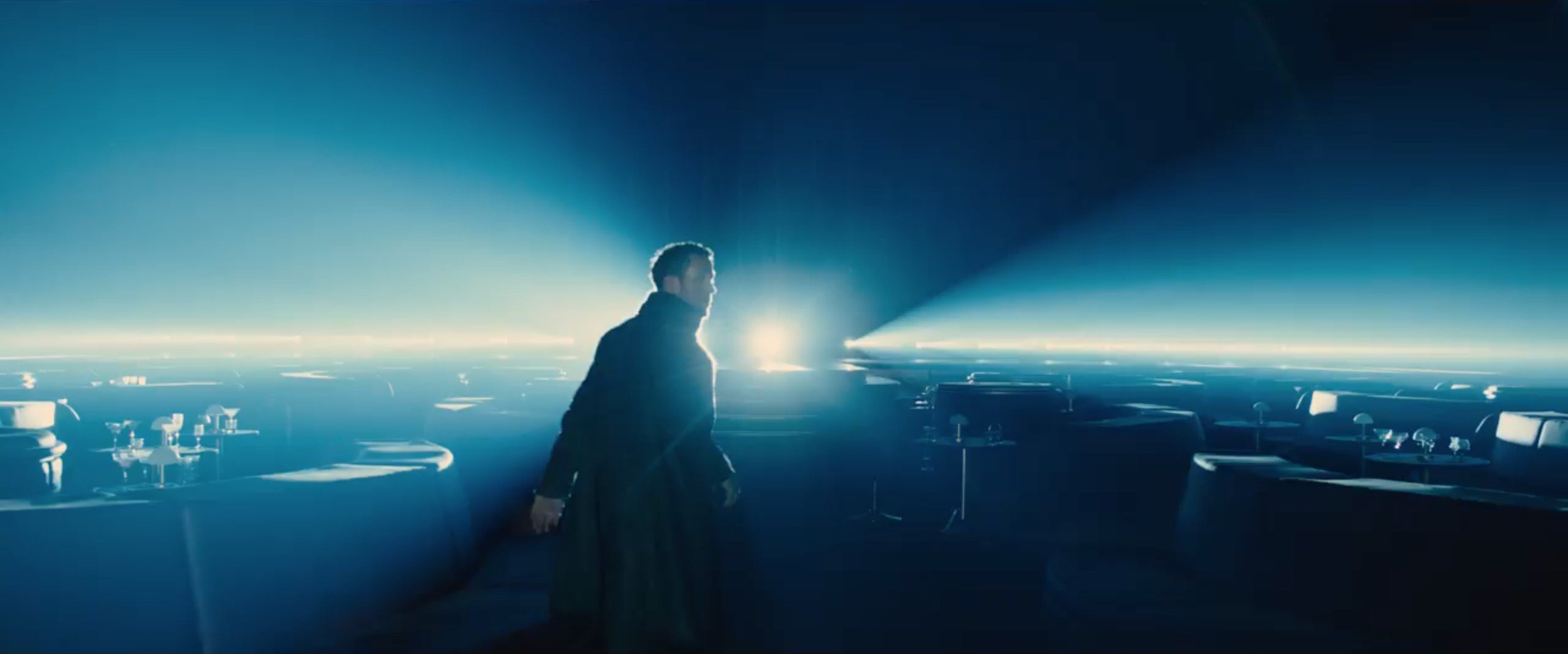

Inside his apartment, however, K is free to use artificial trimmings and trappings to create the best approximation of a normal human existence that he can. The day he slays Sapper winds down with him listening to Frank Sinatra smoothly croon his way through “Summer Wind” and enjoying the attentions of the pretty Joi, who pretends to cook meat and fries for him and coos, “I missed you, baby sweet.”

Is K’s bond with Joi the equivalent of a flesh-and-blood romance? Hardly. Still, there’s something glorious about the moment when he presents her with an “emanator,” a skinny device that allows her to escape the confines of their apartment. For the first time in her life, she’s able to sojourn to a dark rooftop and feel the electric thrill of rain touching her skin—an image that brings a tender expression to K’s stiff features.

Literally, that moment is hollow (if K is a computer, Joi is a calculator); emotionally, it’s a wonder. K and Joi may be second-class citizens in the eyes of callous overlords like Joshi and Wallace, but they take their happiness where they can get it. Society may deny them the right to be called humans, but it can’t stop them from clinging to small but ecstatic scraps of magnificence, like holding each other while the rain beats down.

2. The mystery of the missing child expands the “Blade Runner” mythos

It turns out that the tree where K finds those lone flowers hides a secret: a box full of bones. They look human, but they belong to Rachel (Sean Young), the elusive, glamorous replicant who became Deckard’s lover in the first film. Apparently, Rachel has been dead for decades, but an examination reveals evidence that she may have left something behind: a child.

You can’t overstate just how revelatory it is that a replicant—even just one—could procreate. For Joshi and Wallace, the very idea is a threat; for K, it represents unexpected and miraculous possibilities for his future; and for the replicants as a species, it crystallizes the irrefutable of the wrongness of their enslavement. Scott’s film never shook the foundations of its futuristic society; watching “2049,” you get to watch the pillars of that foul dystopia begin to quake.

It’s in the best interest of Joshi to hold them in place. “The world is built on a wall the separates kind,” she declares imperiously. “Tell either side there’s no wall—you bought a war. Or a slaughter.” She recognizes that if replicants realize that one of them conceived a child, it could inspire them to rebel against their masters. Thus, she sends K to “erase” the child.

Wallace sends his own replicant to probe the mystery: the slick, impeccably groomed Luv (Sylvia Hoeks, whose ferocious cool could probably turn the Terminator to ice). Luv, however, has a different set of orders: Wallace wants her to abduct the child, who he believes can make possible his dream of adding a procreation feature to his replicants. Like Joshi, he wants to insure the supremacy of the human race, but via different means: by birthing countless new slaves so humanity will have the manpower to “own the stars.”

But who will pay the price for Wallace’s ugly ambition? It doesn’t take long for K to wonder if it might be him. A series of clues—a date carved into that tree, a toy wooden horse buried in a furnace—force him to consider that he may be Deckard and Rachel’s son: a “real boy,” as Joi puts it. That prospect fills K with terror (if it’s true, he tells Joi, he’d be hunted by someone like him).

Yet he can’t resist seeking out Deckard, who he has never met before. Nothing can change the fact that K is a replicant, but he seems to believe his existence would have more value if he was born instead of made (“To be born is to have a soul, I guess,” he says).

It may be that K also glows at the idea of being the only one of his kind to have a true mother and father. But the beauty of “Blade Runner 2049” is that it shows that the existence of a replicant child has meaning that extends beyond one life. Unbeknownst to K, Wallace, and Joshi, a replicant uprising is brewing under the leadership of Freysa (Hiam Abass), a one-eyed revolutionary resplendent in an ebony gown. If even one replicant can conceive, Freysa declares, “[W]e are our own masters.”

To some, that idea may not make sense—just because Rachel could give birth doesn’t mean that Freysa and her followers could do the same. But Villeneuve understands that the meaning of the child is symbolic. As much as it’s a threat to Wallace and Joshi, it’s a reminder to the replicants that they deserve the same rights as humans. And that gives them what the androids of Scott’s film never had: a reason to rise up not as individuals, but as a people.