Just as cinema and its techniques evolved from the beginning of the 20th century, an interesting parallel presented itself in the increasing industrialization of modern life from this time onwards. Both became intertwined; the urban landscape provided the film industry with the infrastructure and resources it needed to thrive, with cinema helping to shape how we viewed and understood the urban form.

Finding a prominent starting point in the Weimar Republic’s fascination with the future of modern metropolises in the 1920’s, filmmakers began to use cities more and more for inspiration, with all facets of its form being explored.

Consider, for example, the dark visions of the New Hollywood movement: films like Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver (1976) portrayed New York and the urban realm as chaotic and dangerous, an alienating place to find oneself.

Given this close connection, it was only natural that certain filmmakers focused their attention on specific places that they had a greater feel for. By delving deeper into one city, they could reveal more about its interior life and daily existence. This list looks at 10 prominent connections, beginning with the likeliest and most obvious example.

1. Woody Allen – Manhattan (New York)

The most stereotypical example on this list, Woody Allen became renowned as the New York director. It’s important however, to narrow this down: for a city of New York’s size and magnitude, it would be impossible for one person to capture what it meant to live there—the experiences of its citizens vary too vastly. Therefore, it’s more pertinent to say that Allen’s work detailed Manhattan life, especially a middle-class, intellectual Upper Manhattan lifestyle.

A comedian by trade, after starting out making pure comedy films like Bananas (1971) and Take the Money and Run (1969), Allen began what could be termed his more dramatic Manhattan period in 1977 with the iconic Annie Hall (1977).

The film reflected his intense passion for the island of Manhattan. A wryly humorous passage compares New York and Los Angeles, with the West Coast city being gently mocked for being less intellectual and appealing. But while for Allen’s character, Alvy, Manhattan is the center of the modern world, Los Angeles seems to hold something more for Diane Keaton’s Annie, a greater freedom, as if saying that New York can be viewed as cold and alienating to others.

The city’s landmarks were commonplace in his films, including the mesmerizing opening to Manhattan, as Gershwin plays over a montage of Manhattan images while Allen narrates drafts of his characters’ book about a man in love with the city.

His films even created new Manhattan landmarks, like the bench overlooking the Queensboro Bridge. He strayed from his beloved city a few times over the decades, sometimes making films about other places (Blue Jasmine (2013) and Vicky Cristina Barcelona (2008) for example) but Manhattan is what Woody Allen knows and understands.

While the accusation may be levelled at him that he portrayed an elitist and unbalanced view of the city, during a time in its history rife with violence and social problems, this is somewhat unfair.

Allen depicted the life that he knew, just like Spike Lee, and Scorsese before him; an auteur can only create out of what he has at his disposal. And, additionally, it could be argued that his films helped in creating a new and positive image of Manhattan. Culture and intellectualism remained and were thriving, and Allen was at the center of this.

2. Jean-Luc Godard – Paris

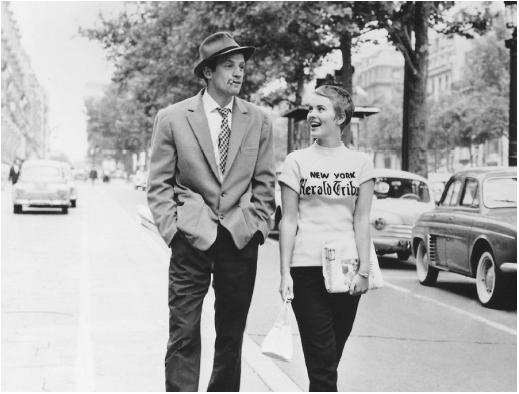

Perhaps, along with Allen, the truest city auteur on this list, Jean-Luc Godard became the most renowned director part of the chic and influential French New Wave that exploded onto the cinema landscape in the 1960’s. He shot his films in real locations as much as possible, in order to establish his filmed city as a real geographical space.

Indeed, another director of the period, Eric Rohmer said that the New Wave ‘was born from the desire to show Paris, to go down into the street, at a time when French cinema was a cinema of studios’. Godard liked to create his films without a full script, favoring improvisation and perhaps reflecting a key condition of filming in an urban place, dealing with the uncertainties of production.

While Los Angeles came to be known with one film genre, and Berlin was related to the idea of modernity, Paris, through the subjectivity of Godard and others implicating their narratives within the dimensions of the city, acted as a pure emblem of place; Paris was Paris. France at this time was steeped in American culture but the Paris depicted by Godard wasn’t a romantic, Americanized portrait.

Rather, his films ironically played off the Hollywood influence, reinterpreted with the French arthouse sensibility. The influences were definitely acknowledged but played off with a wink and a smile by the auteur. For a city so synonymous with its nation, Godard felt a responsibility to reflect what Parisian life was like during this period.

His work highlighted the post-war anxieties as globalization lead to the growth of American and consumer culture; consider the famous quote from Masculin Feminin (1966) ‘this film could be called The Children of Marx and Coca-Cola’. For Breathless (1960), it was both a love story and an anti-love story, playing with the conventions of Hollywood romances and eliminating them when the film ends in tragedy. At once intellectually astute and aesthetically pleasing, Godard’s output encapsulated Paris: cool and sophisticated while being philosophically and politically engaged.

3. Federico Fellini – Rome

As he said himself, ‘When I found Rome, I found my world’. Federico Fellini spent most of his life in Rome, shooting the majority of his films in the famed Cinecitta studios. The city and the director were the perfect partnership – Rome inspired and intimidated Fellini in equal measure. He found wonder in the fact that the city’s citizens could live and work contentedly amidst Rome’s ancient and imposing landmarks; this he admired greatly about the Romans. He was fascinated by its dense history and this showed in his cinematic output.

Within a square kilometer one could view Egyptian pillars, baroque churches and medieval structures and this complexity Fellini felt mirrored the Roman identity—at once warm and pleasant, and haughty and passionate.

In one of the most iconic and romantic depictions of a city, La Dolce Vita (1960) followed Marcello Rubini, a journalist over one week in his search for ‘the sweet life’. Marcello is a gossip journalist covering the affairs of film stars who yearns to create more meaningful output and this contrast captured his existential struggle: an intellectual trapped in a world of excess and fame that was Rome’s popular culture at this point in the 1950’s.

Fellini showed the thriving cafe society of post-war Italy. An astonishing 80 Roman locations were created at Cinecitta for the film, but perhaps the most famous scene was shot on location at the Trevi Fountain. Indeed, the fountain became so synonymous with the film that it was turned off and covered in black when the actor who played Rubini, Marcello Mastroianni died in 1996.

In his most explicit homage to the city, the semi-autobiographical Roma (1972) portrayed Fellini’s move from his hometown of Rimini as a youth. With a simplistic plot, the Eternal City herself was the foremost character. He contrasted differing visions of the city: Roman life during wartime and modern life in the 1970’s.

Under the Fascist regime, scenes showed how people congregated in large numbers in public spaces, such as cafes and squares, and Fellini emphasized the upheaval that occurred as modernization moved the people from gathering together to navigating the city in their cars and motorcycles. While of course not missing a life under the threat of war, he showed that something was lost in the city in the past decades: a stronger city community.

To the outside world a place of beauty and sophistication, and while not an aspect Fellini neglected in any sense, what his work showed was the surreal and changing nature of Rome; here was a city that had managed for 3000 years, he seemed to say, and would manage for 3000 more, in whatever capacity it chose to.

4. Abbas Kiarostami – Tehran

The greatest director to emerge from the rich Iranian cinematic landscape is Abbas Kiarostami. Born in Tehran, he was raised in the city and studied there too; indeed, after the 1979 revolution, he was one of the few filmmakers to decide to remain where he was, instead of fleeing. Kiarostami himself credited this decision as helping his filmmaking ability and future immeasurably.

While he filmed in various parts of Iran, like in the small town of Koker for the Koker trilogy, many of his most well-known works take place in and around Tehran. It should be noted that there are other directors who could claim to be associated with the city – Asghar Farhadi may present more realistic portrayals of the place today, and Mohsen Makhmalbaf may have been more politically engaged – but no one used such an inventiveness and had such a sense of poetry in showcasing Tehran.

Kiarostami liked to mix documentary and fiction to create his films, as seen in Close-Up (1990) and Ten (2002). The former tells the story of a man who impersonates Makhmalbaf, in the process deceiving a Tehran family into thinking that they would be a part of the director’s newest film.

Close-Up featured all the people actually involved in the events, portraying themselves. It’s an impossibly intricate and layered masterpiece. It stands as a brilliant insight into what is, surprising to some, a city and country devoted to cinema: we have the well-off family so enamored by the possibility of being in a famous Iranian film that they’re hoodwinked by a local nobody; we have said local, Hossain Sabzian, a passionate cinephile who longed to be a renowned filmmaker, given his best chance to live his dream.

Include the auteurs Makhmalbaf and Kiarostami making appearances and a rich tapestry of Iran and its love of cinema emerges. Ten, meanwhile, featured 10 scenes each depicting a conversation between an unchanging female driver and a variety of passengers as she drives around Tehran. Again, the cast were untrained amateur actors and the narrative included elements of the actual lives of those in the film.

Exploring the social problems in Tehran at the time, particularly for the women driver, Ten felt like more than a film about Tehran: it felt like a unique work, made by its people. Another of his finest films, Taste of Cherry (1997), follows a man named Badii driving around the city looking for someone to do a job for him, eventually revealed to be the task of burying Badii’s body after he kills himself.

The people he asks give an idea of Tehran’s ethnic identity: he encounters a Kurdish soldier and an Afghan seminarist to name two. Kiarostami then breaks the fourth wall by including footage of himself and his crew working on Taste of Cherry; we see the actor who plays Badii lighting up a cigarette.

Kiarostami could be judged to be saying, by doing this, that life will go on in Tehran, despite its fragility. Through these works, Kiarostami made more than just films regarding his home city, created something more than just fictional narratives about the place: rather, he encapsulated Tehran by including its citizens and allowing them to have a voice in their own portrayals.

5. Billy Wilder – Los Angeles

Los Angeles, being the home of Hollywood, has one of the richest cinematic histories of any city. The imprint of several noteworthy directors can be associated with it, owing much to its mass sprawl (think David Lynch or Paul Thomas Anderson). However, one man came to have a deeper connection with the city. Billy Wilder created two of the seminal film noir films, Double Indemnity (1944) and Sunset Boulevard (1950), which both became synonymous with a certain vision of the City of Angels and Old Hollywood.

The genre associated the city with the themes of isolation and alienation, increasing the viewers idea of Los Angeles as a space of urban and moral decay. As a recent emigre to the city from Germany seemed to make Wilder the perfect candidate to capture these feelings of transition and loneliness.

In ‘Double Indemnity’, the black and white scenes of lonely drive-ins, bowling alleys, even the inside of the femme fatale Phyllis Dietrichson’s house displayed an unnerving isolation and darkness. It’s also the overarching feeling of the city that makes Walter Neff, the insurance salesman susceptible to Phyllis’s seductions.

Wilder, owing to his working in the studio systems, did little actual location shooting; instead, a tapestry of Los Angeles was created by the characters referencing places in their dialogue, mapping out the city for the viewer through the unfolding narratives. Walter’s voiceover, for example, marks the precise location for each change occurring in the story.

‘Sunset Boulevard’ also presented the psychological turmoil of alienated characters, this time in the claustrophobic world of Old Hollywood. In the character of Norma Desmond, the silent-film star, left behind in the sound era, Wilder effectively highlighted the ruthless nature of the business. Perhaps owing to his outside beginnings, he managed to have a more truthful and accurate representation of what it was like to exist in the Los Angeles and Hollywood of this time, where everyone was out to get you and everyone only cared for themselves.