This list of films is necessarily inadequate. There are a large number of truly great films to have received a hundred percent critically favourable reviews. It would have been desirable to select silent classics of German Expressionism such as The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, Hitchcock’s drama Shadow of a Doubt, Kieślowski’s Red and especially the films of Satyajit Ray, to name but a few omissions.

Nevertheless, the selected films were picked not only on the basis of their diversity but also on their commonality. Almost every film picked is aesthetically unusual and almost every selected film analyses the political or social structures that shape everyday life (although sometimes within a historical period different to our own day).

10. The Conformist

Bernardo Bertolucci’s greatest film, The Conformist is a surprisingly colourful and vibrantly photographed exploration of Italian fascism, perhaps channelling the aesthetic dynamism of modernism. The film explores the dangers of conformism and the very modern notion of the agent who lacks agency, lacking both a moral identity and integrity.

The Conformist follows Marcello, who through flashbacks is revealed to have had an isolated childhood, estranged by his wealth and further alienated from society as he believes that as a youth he killed his predatory chauffeur. His guilt is ultimately expiated but in what Bertolucci has called a ‘negative catharsis’, namely by sinning more rather than making amends. Throughout his life Marcello adapts to his situation, often in a chilling manner when he works for the fascists.

The self as a vacuum emptied of selfhood, as adaptive was memorable explored by Woody Allen’s masterpiece Zelig which also ranks at 100% critical approval on Rotten Tomatoes. Bertolucci expertly conveys the existential themes from Alberto Moravia’s novel of the same name in relation to an exploration of sexuality, alienation, illusion and totalitarianism. If one is a lover of Bertolucci’s exploration of complicity, responsibility and guilt, one may also enjoy the films of István Szabó.

9. Vagabond

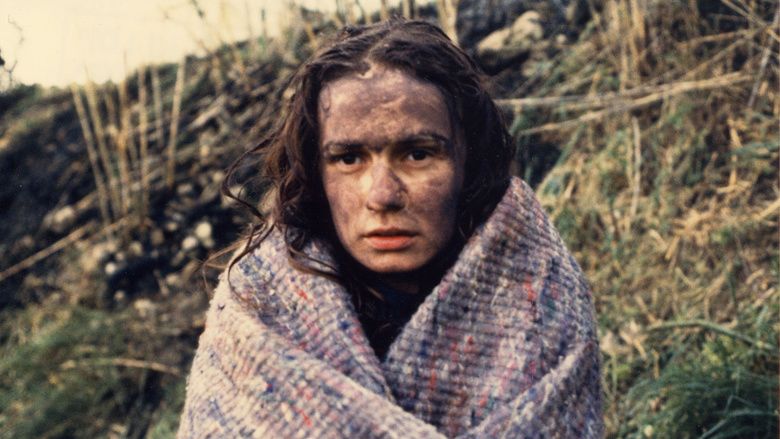

Agnès Varda’s haunting film explores the death of a woman vagrant named Mona. We are introduced to Mona by her corpse and come to learn the circumstances that led up to her death. We also discover the people who crossed paths with her along the way her fated journey. By the end of the film, Mona still remains enigmatic, but her sense of defiant free-spiritedness is nevertheless apparent.

The French title of the film Sans toit nil oi means no shelter no law conveying a sense of the protagonist as exposed but also locating her story through a negativity, of being without. We learn about her through an investigation into the circumstances of her death, but we also glimpse her as a human being searching.

There is a long tradition of female existentialist figures suffering or dying, especially in French cinema, think Godard’s brilliant Vivre sa vie. But there’s something different about Vagabond, some sincere desire to know its character and not patronise her—as with Godard’s film where Nana is killed illustrating her inability to determine her life against the cold linguistic logic of the modern world. This film on the contrary is a call for justice underpinned by an approach of respect and sometimes respectful distance for and toward the protagonist. It is a film that every cinephile ought to view.

8. Tokyo Story

Ozu’s masterful Tokyo Story concerns an elderly couple, a mother and father, who travel to visit their adult children in Tokyo. It transpires that their children have no time and interest in them. The only one who wishes to meet them and seems to display feelings toward them is their daughter-in-law, who is widowed and desperately lonely.

But the film is more than a sentimental, tender narrative about loss and an analysis of family ties. It is also a film about alienation and hushed desperation amid the rhythms of modern life.

7. Un Chien Andalou

Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí created one of the most recognisable sequences in film history. Opening with a graphic scene where a barber slices a woman’s eye open as a cloud divides the moon, we are violently thrust into an altered reality severed from conventional cinematic perception. Often considered the first surrealist film, it is a great work of cinematic art, capturing the sadism and cruelty embedded in the modern psyche.

The film explores violent and sexual fantasies buried within bourgeois culture. Fittingly, the film is not altogether coherent in its objectives. Buñuel was a leftist while Dalí had little interest in politics. For Dalí surrealism was a way of liberating oneself from moral, political concerns and surrendering to aesthetic realms that were at once above and below the surface of our reality.

At times, one intuits that the sequences of the film reflect not so much the deplorable fantasies of the bourgeois as celebrate their Sadean realisation. This antithetical focus meant that Dalí split with Buñuel over their next, more ambitious collaboration L’Age d’Or, which further pronounced the difference between their outlooks.

6. Citizen Kane

Citizen Kane remains one of the greatest films. With its innovative deep focus, its unusual narrative structure and the idea that a missing reference remains unknown to a key character by the end of the film. As the wealthy Kane dies he utters the word Rosebud which inspires a journalist to decipher what the word means, only for the film to end without him ever learning that Rosebud was the name of Kane’s childhood sled.

The film leaves open whether Kane mentioned Rosebud longing for a false and idealised past or whether he was merely replaying his life. The remembrance of his sled may in fact be the remembrance of his childhood fetish—in the sense Freud used the term fetish—namely a way to cope with trauma. We are transported from Kane, the wealthy recluse to Kane the child of a poor family, leaving what appears to be a happy life until we learn that his father beat him, and his mother is desperate for him to escape both his abusive father and to offer him an education.

Despite the various easy explanations we now offer for Kane’s reminiscences—most of which are pop psychology and rather twee (such as the idea of recasting the small things as really big things after all)—the film remains a testament to what we cannot know and the various deceptions of power. Given fake news, and the current US president, the framing of business and power and the idea of a news cycle descending into triviality and scandal, while capturing a sense of revolutionary times, the film is a powerful warning of the trappings both of power and powerlessness. It is reminder of the futility of the American dream.

Even the technical use of deep focus conveys an exploration of the human subject up against the world. The use of deep focus allowed Welles to use theatrical space but contrary to the view that such a device merely allowed Welles to move from theatre to cinema, deep focus combined cinematic shots, affording Welles the ability to capture the pathos of the close-up and the bathos of the wide-shot. As such, a sense of significance granted by the close-up is undercut and undermined by the insignificance of the wide shot, and the noir chiaroscuro underpins the atmosphere of despair and the Faustian bargain of fame and fortune.