Movie production breeds conflict. Films take years to make, involve thousands of people, ridiculous sums of money, and the biggest egos in the world. This combines for a chaotic environment where any misstep in the process means the loss of money, careers, reputations, and renown—the latter of which is most coveted. So much rides on a motion picture’s success that it’s no mystery why the industry attracts and sustains eccentrics. It takes a special type of person to risk his life for make believe, and that person might not think rationally.

Documentaries are at their most interesting when the above qualities coalesce. Film as a subject is as entertaining as film as a medium. Unlike film as a medium, these stories need no punching up; they contain enough crazy characters, multi-layered interpretation, and plot twists to make Hollywood writers obsolete. If desperate for ideas, look no further than a movie about a movie. Charlie Kaufman knew this and exploited it.

Though we’ve included a few token documentaries about the history and techniques of movie making, you may notice a common theme throughout this list: Art’s resistance to compromise.

10. This Film is Not Yet Rated

The Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) is the organization which assigns ratings to movies. From NC-17 to G, these alpha and numeric distinctions can make or break movies, affecting viewership, distribution, and, consequently, box office results. This Film is Not Yet Rated explores the organization, its members, and the censorship and distortion of films at the board’s discretion. These include double standards on issues like nudity, violence, and dark humor, all of which are subjective and, as directors like Darren Aronofsky, Kevin Smith, John Waters explain, incredibly frustrating.

The MPAA comprises a small group of reviewers whose job it is to watch films and decide their distributary fate based on their content. Unfortunately, as the documentary discovers, these people are hardly qualified to judge movies. They’re old, out of touch, admittedly biased, and are hired, specifically, for their cinematic naivety, the reason being that someone not submerged in the minutiae of showbusiness will give a more authentic rating. They’re also slaves of their time and environment, unable to adapt to a mercurial society where obscene content is not the moral aberration it once was.

This Film is Not Yet Rated also takes us through the painful process of having a film—this time, the documentary itself—submitted to the board for screening. Without accreditation from the board, films were basically withheld from wide release, so they were forced to use other, less reliable routes for distribution. The MPAA was a powerhouse, but the power is depleting thanks to autonomous release on alternative platforms.

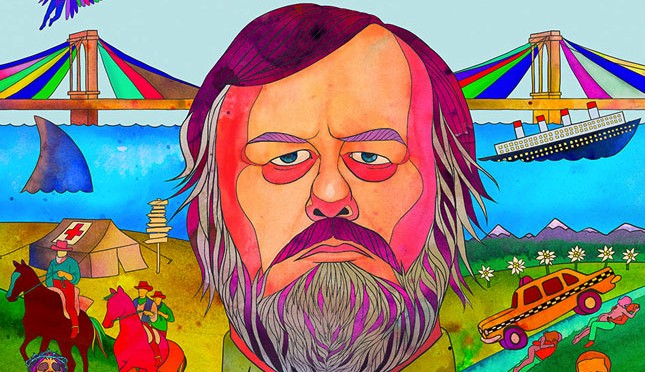

9. Lost Soul: The Doomed Journey of Richard Stanley’s Island of Dr. Moreau

The Island of Dr. Moreau is about a mad scientist who creates grotesque human/animal hybrids with which he populates an isolated island. The fiction is strange, but the film’s production proved much stranger.

Richard Stanley was the man appointed to direct the 1996 film adaptation of The Island of Dr. Moreau. A horror director, known for the British cult films Hardware and Dust Devil, Stanley held the reins of a movie destined for success. It was a famous story, had a huge budget, and had the likes of Marlon Brando and Bruce Willis set to star. But what could go wrong did go wrong, and even more.

Willis dropped out. Val Kilmer was hired. He and Brando became arch enemies, which, compounded with Brando’s standard eccentricities, meant certain failure to the cohesion of the film. Unable to corral the actors, Richard Stanley was fired, but that didn’t stop the bad luck.

Everything from hurricanes to egos disrupted production. Brando was so bad that he insisted on shooting scenes with a bucket on his head, despite nothing of the sort in the script. He would also only read his lines if fed through a transistor radio. Everyone fought, especially with the new director John Frankenheimer. Thanks to horrible weather, the shoot was extended by months. Since this was the Australian jungle, this was not a desirable outcome.

The craziest story is that of the eponymous director. After suffering a post-firing breakdown, Richard Stanley returned to the set in the costume of one of the animal/human hybrids. He effectively hid in the film without anyone knowing. Some scenes with the costumed Stanley were apparently used in the final cut. We can presume that Stanley’s idea was to sabotage the film, but Stanley revealed in Lost Soul that he wasn’t really thinking at all.

The Island of Dr. Moreau was completed, but it’s notoriously terrible. Without the film, however, we wouldn’t have this documentary, and the tales of a doomed production now cinematic legend.

8. Side by Side

The most fundamental part of moviemaking is the film itself. It goes without saying, then, that when an institution as ubiquitous as film is jeopardized, those individuals who have relied upon the format for their careers are unnerved. Side by Side explores the digital revolution, describes its effects on the film industry, and contrasts its pro and cons with that of physical film, the industry standard for a century.

Side by Side is presented by Keanu Reeves, who interviews dozens of film professionals and tracks photochemical and digital film through their respective lineages, entwining expert opinions within a historical context of technical evolution.

Directors like Martin Scorsese, David Lynch, Christopher Nolan, George Lucas, and Lars von Trier are asked for their choice on digital versus physical film. Lynch, Lucas, and Von Trier have fully embraced digital film, while Scorsese and Lynch, though they have indeed shot plenty with digital, still extol the virtues of physical film and shot some of their best movies on thousands of impractical feet of 35mm.

There’s one thing that all agree upon: the digital monopolization is inevitable. The few photochemical holdouts can only hold out for so long. Even Scorsese has adopted digital since the documentary’s release. However, as Side by Side explains, physical film is more durable, and digital innovators have not devised a method through which digital film will last as long as physical. It’s a problem, but one that will no doubt be solved.

7. Video Nasties: Moral Panic, Censorship, and Videotape

Moral panics are generally overblown and superfluous, especially if media is to blame. This documentary describes one of such panics that ensued in 1980s Britain…over videotapes.

“Video nasty” was a pejorative used to describe any gory or sexually violent film. These video nasties began circulating in the early 80s after the advent of home video, sold in video stores before any ratings system restricted the sale to minors. Therefore, extremely graphic content was sold indiscriminately, seen by children of all ages who needed only to visit their local video store. As always happens when culture gets subverted, traditionalists call for the ban on the new art corrupting people’s minds.

The documentary takes us through these contentious years where videotapes were rounded up from stores, seized from homes, and burned by the government. They worked off an official list of 72 banned films, which included I Spit on Your Grave, Cannibal Holocaust, and Faces of Death, but this soon expanded to include any film that could be construed as corruptive, even horror classics like Texas Chainsaw Massacre. The panic lasted until 1984 when a ratings system was enacted for home releases, effectively domesticating the untamed video market.

Through interviews with exponents and proponents of one of the most egregious cases of censorship in the modern world, Video Nasties: Moral Panic, Censorship, and Videotape discovers that the only evidential impact of these video was positive. They influenced a generation of horror filmmakers, including, but not limited to, Neil Marshall.

6. The Cutting Edge: The Magic of Movie Editing

Editing is an indispensable yet unheralded part of movie making. This documentary is a long overdue presentation of movie editors, the unsung heroes of the industry. The very apparent, or unapparent, reason for their omission from popular recognition is that the best editing is that which is invisible. A viewer who recognizes a movie’s editing is, generally, seeing through the wizard and acknowledging the man behind the curtain. There is no better indication of a movie’s failure.

This 2004 film describes the techniques, technology, and history of film editing, starting before editing even existed. Early films were simply continuous shots which ended only when the reel ended. Eventually filmmakers discovered the efficacy of cutting and splicing films for narrative and dramatic effect. Edwin S. Porter’s The Great Train Robbery is the archetype of such stylistic changes, cited in the documentary as revolutionizing the medium.

Following the inception of editing, we watch the evolution from a rogue discipline to a studio-run machine comprising women constructing movies on assembly lines. Eventually directors started noticing the value of collaborating with their dark-room brethren, and editors escaped the confines of the studio to gain creative autonomy. Now editors are auteurs, just as important as the writer and director for shaping a movie, and the last line of defense against mediocrity.