France. The birthplace of cinema. The center stage of cinematic innovation for generations. With revolutionary movements emerging over the years, ranging fromAbel Gance’s poeticism in French Impressionism to the radical nature of Godard of the Nouvelle Vague to the more obscure, modern names like Leos Carax of Cinema du Look.

Regardless of the amount of changes cinema faces over the years, you can be almost certain that one factor stays constant in the context of French Cinema. Pure, artistic innovation. This desire to be different, to break free from the norm through beauty, expressionism, impressionism, style, all of these poetic elements amalgamate into the brilliance that is French Cinema.

The films on this list span almost the entirety of the cinematic history of France, but regardless of how much the films differ from one another, in terms of both style and substance, they still, in one way or another, share the same characteristic of representing what France truly is to the world through the medium of cinema. Without further ado, these are 10 of the most French movies of all time.

10. The Dreamers

The French New Wave and French Cinema as a whole has always been at the forefront of cinematic innovation. There’s just something inherently beautiful and magical about the French that practically cannot be found in any other country of cinema. Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Dreamers, serves as a love letter to these times, replicating the intensity, the rebellion, the freedom that the zeitgeist is notorious for.

It’s undeniable that The Dreamers is an inherently flawed film with poorly developed characters and a haphazard plot, which is precisely the reason why this film is ranked so low on this list.

Nevertheless, it still deserves a spot as the effort made to modernize classic conventions that define the Nouvelle Vague to contemporary audiences in the film is brilliant, and truly exemplifies Bertolucci’s understanding of cinema. His incorporation of callbacks to classic cinema certainly provides a layer of depth and nostalgia to the narrative, if anything, adding to the entertainment value of the film.

A French New Wave film is uniquely a French New Wave film. One can so try, though it can never ever be replicated. With that being said, for what it’s worth, The Dreamers does an impeccable job at emulating what made films like Breathless and Band a Part so timeless even up until today, capturing the idea of what it feels like to live in the moment without any regard for consequence. Not to mention, the added bonus of a cinephile-centric narrative.

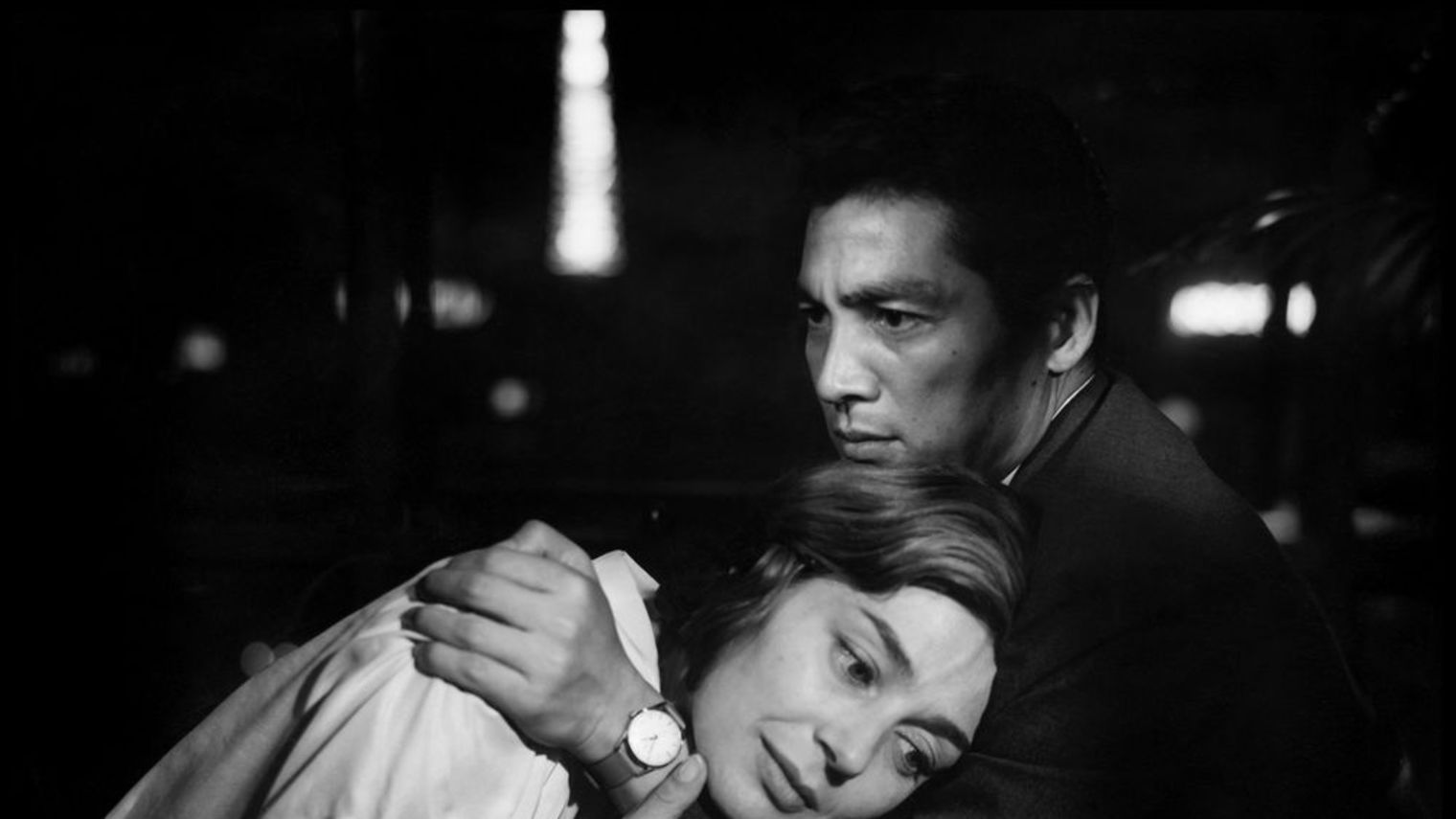

9. Lovers on a Bridge

Perhaps the greatest film to come out of the stylized Cinema du Look movement of the 90s, Leos Carax’s Les Amants du Pont-Neuf offers a very genuine interpretation on this concept of hedonism. Especially compared to his much more idealistic predecessors of the Nouvelle Vague.

Nevertheless, beyond the grittiness and unflinching honesty of its portrayal, what it presents to us is still something undeniably beautiful. It explores the concept of a “starving artist” and the unhealthily alluring nature of such an archetype, glamourizing the beauty and amplifying the ugly.

It explores the lives of two individuals and the increasingly tragic arcs they undertake, slowly amalgamating into a relationship. A truly exuberant and volatile relationship built through an inexplicable spark, interpreted very distinctly by the two characters, giving rise to a world filled with consequence and drama. Leos Carax has certainly progressed to a much more philosophical and surreal style over the last 20 years as a filmmaker.

Though his newer works may subjectively be more powerful, Carax stumbled on creating something absolutely brilliant with Lovers on a Bridge and it truly is a shame that we may never see another film like it by him anytime soon.

8. Hiroshima Mon Amour

Alain Resnais’s Hiroshima Mon Amour is a film completely unafraid to delve fully into the inherently introspective approach to his filmmaking. It’s a film that brilliantly blends elements of nonfiction into an otherwise fictional narrative that, beneath its seemingly impenetrable surface, lies a strong and personal commentary of war.

Resnais, along with the other Left Bank Filmmakers, certainly have a much more distinct style compared to their counterparts and Hiroshima Mon Amour is definitely a much more daunting film to watch as opposed to something like The 400 Blows or Pierrot le Fou.

With the long, self-indulgent monologues and scenes that just demands an unnecessary amount of attention to what is essentially just two people talking, it does admittedly drag on at moments. However, when taken in as a whole, this is a film that, in spite of these inaccessibilities, succeeds in perpetuating what it set out to do.

It offers an increasingly harrowing tale of memory and loss, set against a passing sense of romance between a two distinct individuals with different outlooks of life. These tales are spun and woven so masterfully that it leaves us speechless.

We can’t exactly discern as to what these remnants truly mean specifically, but we’re certain of their emotional impact, not only to the characters, but to us as an audience. More so considering the political and social implications of this film in relation to the Atomic Bomb, juxtaposing the horrors of which with the introspective horrors of the self.

The French identity is certainly a unique one to say the least, and Resnais’s haunting portrayal of that with Emmanuelle Riva’s character offers a moving personification in the film. One that shines in a backdrop of what is essentially a polar opposite to that of France. One that enlightens as well as impacts us beneath the ostentatious nature of his filmmaking.

7. The Rules of the Game

Decades prior before Truffaut and his contemporaries shook the cinematic world, we have the equally energizing works of Jean Renoir of the poetic realist movement. Perhaps the greatest film to come out of Renoir’s filmography, The Rules of the Game offers an interesting and layered statement reflecting the absurdities of a bourgeois war-torn France.

It examines the ever-relevant idea of the upper class wasting their lives away on trivialities and ignoring the bigger picture, descending into a life of unnecessary drama to almost comedic proportions. The Rules of the Game is essentially one of, if not the greatest romantic comedy of all time.

One would even go as far as to call the film a soap opera, with the numerous intertwining arcs and diverse cast of characters that outwardly seem irrelevant in the grand scheme of things. Renoir embraces the stupidity of it all and goes to the absolute extreme, complete with elaborate physical comedy framed with glorious deep focus to rival even the likes of Citizen Kane with the overall effect it produces.

In the history of cinema, there have been many great films that explore society following major historical events such as war, through seemingly unassuming narratives. But very few dare to venture to the comedic side of things with their filmmaking as Renoir so masterfully did with The Rules of the Game.

6. Jules and Jim

When it comes to the subject of the French New Wave, discussions of classics like Breathless and The 400 Blows are inevitable, each being cited as the quintessential cornerstones of the Nouvelle Vague. However, there’s a certain, underrated brilliance when it comes to Truffaut’s Jules and Jim, one that’s unfortunately overshadowed by the magnitude of his earlier work as well as that of his contemporaries.

The film perpetuates the radical stylisations of the Nouvelle Vague that we are so accustomed with, against the backdrop of a love triangle between two best friends. The common themes of hedonism, desire, crime run wild in this film, albeit heavily restrained and controlled with the shackles of realism by the personal touch of Francois Truffaut.

This is, beyond all the infamous extravagance of the movement, all genuine film. A truthful portrait of the strength of friendship, one that transcends the idea of love and even the very conventions that define the genre itself. It’s a film that pushes the boundaries of filmmaking with elements from the movement while still retaining the undeniable emotional impact of cinema, one that examines the notion of loyalty when perpetuated in an environment that forces for a lack thereof.

Jules and Jim, much like most of the other films of the era, is certainly not a perfect film. Nevertheless, the sheer experimentation Truffaut dares to present audiences is commendable enough for us to look past any superficial flaw or mediocrity the film has and accept it as part of the revered canon of the French New Wave.