It might feel like a backhanded compliment to say a movie is great even though nothing happens. We’re accustomed to the idea that a film needs to be constantly moving forwards, with several plot points unfolding at once – be it narratively or simply visually – for us to want to concentrate on it.

But that seems like a rather simplistic point of view, doesn’t it? There are hundred of ways one can make a film, dozens of things one can do with the cinematic language. Claiming nothing happens in a film is not a critic in and out of itself, it can be a bad or good thing.

What ones need to pay close attention to is whether the apparent uneventful nature of the film serves its story and language, and thus creates an engaging and often atmospheric film, or if it just turns it into a boring, hollow viewing experience.

Having that in mind, here are some of the best films where nothing really happens (I mean, they do, but very little actually happens) and why that isn’t a bad thing in the slightest:

10. Blowup

Lauded as one of the greatest works from one of the best filmmakers of all time, Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blowup is a slow-burn of a thriller. An instant classic upon release, Blowup follows a pompous British photographer who believes he unwittingly captured a murder on camera. As he begins to investigate whether his assumptions are true or not, his life spirals out of control.

Claiming nothing happens in Blowup isn’t a fair statement, as a quick glance into the film’s Wikipedia page will show the story’s many twists and turns. What really springs to scene isn’t precisely what happens in the movie, but whether how it happens.

Antonioni has no clear interest in moving the story along at a rapid pace, the film is filled to the brink with long scenes of the protagonist wandering aimlessly through the parks and streets of London. He encounters several people who at first seem to be following him on account of the supposed murder he was a witness to, but ultimately end up being mere nuisances and distractions.

Antonioni has always been fascinated with incommunicability, with characters who seem unable to grasp at what’s happening around them and, due to their ignorance, are bound to wander and ponder endlessly. Sure, Blowup has its moments of tension and suspense, but Antonioni seems to conduct the story to elicit mood and atmosphere, to convey through sound and image the state of mind of the lead character.

It’s a thriller that is almost an anti-thriller in its development. It’s no surprise Blowup, even with is captivating narrative, is a slow moving and quite difficult film to watch, especially for those unfamiliar with Antonioni’s body of work.

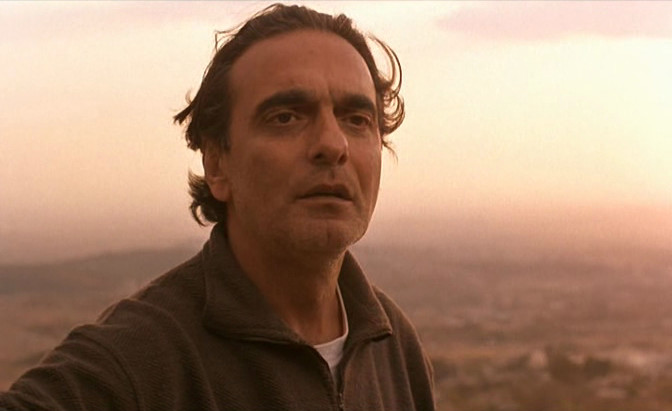

9. The Taste of Cherry

One of Abbas Kiarostami’s greatest masterpieces – which is saying a lot, considering the filmmaker’s track record -, The Taste of Cherry is a profoundly beautiful yet heartbreaking film, one that manages to be approach heavy themes in a subtle and delicate way.

Taste tells the story of a man who drives around a small Iranian village in search of someone who’ll bury him after he commits suicide. He encounters a myriad of people who are concurrently shocked and moved by his proposal, and who become involved in his quest some way or another.

Moving at a leisurely pace, Taste of Cherry is a testament to Kiarostami’s commitment to a slow, intimate cinema, one that burns with lost looks and long stretches of silence. The lead character is often quiet, listening patiently to the tales and words of those he drives in his car. People tell him of their lives, try and convince him to keep on living, say they have thought of suicide as well but opted against it. The movie shows these exchanges, never making one more important or more explosive than the other, they are all equally delicate scenes of intimacy and quiet conversation.

As the movie approaches its ambiguous ending, one realizes that it doesn’t seek to tie the story in a nice bow or give the A 34B no scenes of moralistic epiphany, no real change in the characters.

The film moves on as we listen to the stories being told and watch the car moving through the hills. In the end, as the protagonist lies awake in a grave and a storm begins to rage on, we see nothing has really happened, but so much has been revealed in the subtlest of manners.

8. Gummo

Coming from one of the most interesting and provocative auteurs of the turn of the century, “Gummo” is perhaps the quintessential view of American midwestern poverty and its doomed, hedonistic youth. Deeply unsettling and depressing, it’s a feature that seems deprived of narrative, where the characters’ many (awful) actions almost never amount to effect or consequence, and where everyone just drifts away at life.

Exploring such themes as prostitution, mental illness, sexual abuse, suicide and euthanasia, “Gummo” patiently follows its characters as they wander aimlessly through a hurricane-devastated small town in Midwestern America.

Depicting a wide myriad of characters which range from two mentally handicapped teens who brutally kill cats to a man who prostitutes his down syndrome afflicted sister, “Gummo” can sure be a difficult film to watch. It is a dark, abrasive film, uninterested in silver linings or faint rays of hope.

What makes “Gummo” such a tough yet fascinating viewing experience is the fact that nothing really seems to amount to something. Actions, no matter how horrible, yield no discernible consequences. People live in houses filled with cockroaches, kids bathe in dirty contaminated water, recently-freed convicts participate in indoors mosh pits that destroy their entire homes, teens prostitute their siblings.

And none of those occurrences are given more time or attention than the other ones, they all seem to be so utterly banal and worthless that one goes from questioning why these characters act the way they do to sympathizing – from a distance – with these peoples’ predicaments.

It’s a terribly unerving film because it shows that as nothing really happens that holds any weight, all these kids have to do in their unending free time is find new and increasingly destructive ways to get a kick out of something, anything. No matter how violent or deranged that turns out to be.

7. Last Year at Marienbad

If anyone ever told you they can easily explain Alain Resnais’ “Last Year at Marienbad”, they are lying their teeth out and you know it. A cryptic, experimental film by nature, it is generally listed in everyone’s polls of most complicated and convoluted movies ever made and it is still analyzed to this day, over 60 years after its release.

“Last Year at Marienbad” centers on an unnamed couple who meet in a luxury hotel but may have actually met the year before and may have started an affair. Oh, there’s also a third man that may be the woman’s husband. I guess. I don’t really know, it’s a baffling spellbinding film that continues to challenge viewers.

Its repetitive, confusing plotline – which many refer to as dreamlike – constantly toys around with space and time. It’s not unusual for the film to present impossible cuts and juxtapositions; the characters often continue a same line of dialogue in two separate locations, whole scenes are repeated throughout in different sets, under different circumstances.

As the movie leads you into its unique atmosphere, it becomes increasingly difficult to discern whether something is legitimately happening, has already happened, is a figment of someone’s imagination or is even a dream (or a dream of a dream, as some fans have posited).

In the end, nothing really happens in the film that holds true narrative weight; the movie refuses any sense of closure as it stays close to a “mental continuity” rather than a classic film structure. Marienbad is told as if through dreams and memories (not unlike Tarkovski’s “The Mirror”, mind you), which constantly phase together in an uncertain and agonizing manner.

You’ll have a hard time following this film, but if you manage to walk through the apparent nothingness of the plot, there is a lot to be seen, heard, felt and admired in Resnais’ great work.

6. Frances Ha

Noah Baumbach is infatuated with New York and its types. Be it the forty-year-olds dealing with midlife crisis in “While We Were Young” or the tempestuous, borderline nihilistic young adults of “Mistress America”, almost every one of his characters are drenched in the big city melancholia of New York.

Nowhere in this more apparent than in “Frances Ha”, one of Baumbach’s greatest achievements. Chronicling a couple of weeks in the life of the titular Frances, the film is a look inside the trials and tribulations of a seemingly privileged group of people, who still struggle to make any sense out of their lives or find joy in their everyday activities.

Frances’ odyssey of self-discovery is brought to the front when she is forced to move out abruptly, at which point she relocates to the house of a friend. Several conversations ensue, of themes that range from insatisfaction to insufficiency, and even a couple of trips to California and Paris (!).

However, no decision or action made by Frances seems to affect her life in any discernible way. What makes the film so interesting is that there is no real dramatic ark in the way one would expect from an American film. Frances doesn’t get involved in a tragedy which propels her into a life-changing journey from which she comes out as a different person.

As Frances moves along her life, she realizes that every decision she’s made – be it impulsively or deliberately – to change herself and her life has come to no fruition because she doesn’t need to change; she only has to find ways of being fulfilled with what she has and who she is.

“Frances Ha” is really a film about a woman who tries to do everything she can to change her entire life, only to figure out she hasn’t done anything at all. In the end, nothing happens because it doesn’t need to.