Talking about “the best (individual) shots in film” is a difficult task, not only because there’s thousands of equally deserving entries, but because meaning in cinema is usually better conveyed through the succession of frames, shots, and sequences.

Concepts like “affinity” and “contrast” play a crucial role in achieving meaningful and lasting images, and although it would be easy to just name those that display the most aesthetically pleasing density within their borders, the ones featured here are just meant to show how filmmakers try their best to communicate with the viewer through the visual form.

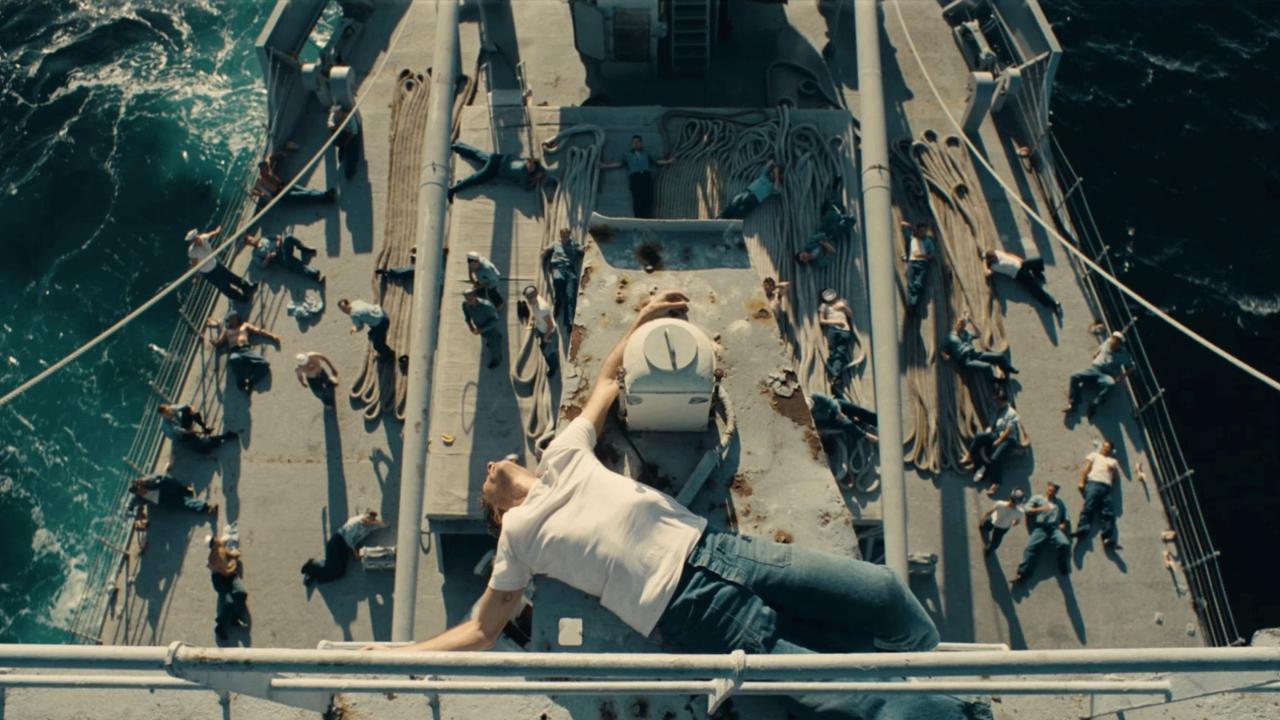

30. The Master (Paul Thomas Anderson, 2012) – On the top of the boat

Even though it is usually considered best suited for spectacle-driven films, Paul Thomas Anderson opted to shoot 2012’s “The Master” in 65mm, demonstrating that the richness of the format “can work just as well for intimate and character-driven stories” as FotoKem’s Andrew Oran, stated in an interview about the film for PVC.

However, there’s no doubt that the movie takes advantage of the high detail offered by its larger film gauge in shots like the one with Freddie Quell (Joaquin Phoenix) laying on the top of the boat in the beginning.

This shot is a perfect example of some well-known compositional rules. Division in thirds, the triangle shape made of the deck of the boat, and the difference of size between Freddie and the other soldiers. It’s a really busy but captivating image that shows the ingenuity of its director.

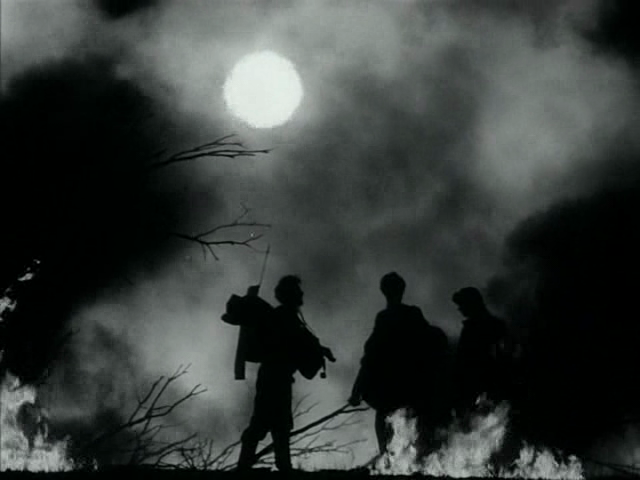

29. The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (Andrew Dominik, 2007) – Jesse James just before the train robbery

The dark figure of Jesse James (Brad Pitt) holding a lantern while being backlighted by the locomotive of a train along the fog and trees is one of the most celebrated moments found in the acclaimed cinematographer Roger Deakins’ career.

In addition to the obvious aesthetic power displayed by the image, the shot also provides a perfect picture for the character portrayed by Pitt. A man whose legend has engulfed and erased his whole persona, making him only a shadow for those who surround him.

28. Black Swan (Darren Aronofsky, 2010) – Nina falls in slow motion after her performance

Shot for the most part on Super 16mm by its cinematographer Matthew Libatique, “Black Swan” is a grainy, fraught, and frenetic descent into madness. The film moves unrelenting towards Nina’s (Natalie Portman) debut as the White/Black Swan in Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake, but its most inspired moment comes right after the function ends.

The film makes great use of visual contrast to communicate the sense of bliss and relief felt by Nina as she falls after her performance. The shot, unlike the rest of the film which has a marked sense of abandonment thanks to its handheld style, is almost artificially symmetrical and steady, especially thanks to its use of slow motion. It’s just a perfect example of how visual design can communicate emotions through challenging the visual language that has been presented to viewers throughout the film.

27. Yojimbo (Akira Kurosawa, 1961) – Sanjuro faces Unosuke and his men

The film that would later be remade by Sergio Leone as “For a Fistfull of Dollars” has some of the most lasting images from the acclaimed Japanese director Akira Kurosawa and the legendary cinematographer Kazuo Miyagawa.

Miyagawa used telephoto lenses to render the small town and the fights from the film. The shot where Sanjuro (Toshirô Mifune) faces Unosuke (Tatsuya Nakadai) and his men is made even more tense and dramatic thanks to its blocking and the long lens, which make the figure of the former feel even more trapped and overwhelmed at first sight.

26. HÄXAN (Benjamin Christensen, 1922) – A woman sleepwalks naked through the forest

Based on the 1486 treatise Malleus Maleficarum, this Swedish–Danish silent documentary of sorts, which was considered at its time too graphic and morbid due to its depictions of sex and violence, is nonetheless a heart stompingly gorgeous film that deals with the accusations of witchcraft that took place during the 15th century and onward.

The film is structured through little vignettes that provide insight into the realm of superstition, and while all of them are equally uncanny and intriguing, the image of the naked woman walking through the forest in the dark after being seduced by the Devil is still as eerie and ghostly as anything that has come out in theaters since the release of the film in 1922.

25. Un Chien Andalou (Luis Buñuel, 1929) – Before the razor slashes the eye

With its most famous frame, “Un Chien Andalou” was not only anticipating the shocking scene that would follow in the film, but also declaring, intentionally or not, the birth of a new way of filmmaking. The film was inspired after a meeting between Buñuel and Salvador Dalí at a restaurant where they talked about some dreams they had, which ended up becoming the film’s main theme.

Almost 90 years later, the movie not only still retains its subversiveness and is commonly taught in film school, but it is actively cited as one of the most original and important works from the medium.

24. The Tree of Life (Terrence Malick, 2011) – Jessica Chastain walking towards the sun

If “The Tree of Life” is a film built around the duality between nature and the divine, Jessica Chastain’s character is definitely the incarnation of the former, balancing Brad Pitt’s portrayal of the cold and angry father.

Emmanuel Lubezki used natural light almost exclusively, alternating between 35mm, 65mm, and IMAX formats in order to enhance the impact of certain shots and scenes. Lubezki’s affinity for low angles intensify the perception of Chastain’s character as the representation of the “mother.” Her figure walking toward the light in the plain field is both exhilarating an a testament for Malick’s late non-theatrical approach to filmmaking.

23. Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (Michel Gondry, 2004) – Frozen lake, watching stars

In the same way that it works as a moment of visual reflection after all of the fast-paced sequences taking place in Joel’s (Jim Carrey) mind, this shot from the 2004 romantic film written by Charlie Kaufman and directed by Michel Gondry is also the one that best encompasses the main conflict of the story: the falling romance between Joel and Clementine (Kate Winslet).

While both of them are fixated on the beautiful night sky, the crack in the ice beside them reminds the viewer how fragile, worn–out, and ultimately doomed their relationship really is.

22. Letter Never Sent (Mikhail Kalatozov, 1960) – The man in the snow desert

The image of Sabihin (Innokenty Smoktunovsky) crossing the white snows of central Siberia after losing all of his fellow companions is both anguishing and beautiful to behold.

It is not clear where the snow ends and the sky begins, as the only points of reference are the Sun and Sabihin’s dark figure. The shot is a white hellscape that surrounds the protagonist, showing his uncertainty and the helplessness that he faces.

21. The Third Man (Carol Reed, 1949) – The silhouette emerges from the tunnel

One of the greatest British films, the evocative visuals of “The Third Man” by cinematographer Robert Krasker and director Carol Reed have been an object of study since its release in 1949.

The elongated shadows that haunt the streets of Vienna have become part of the film noir mythos, but watching Holly Martins (Joseph Cotten) emerge from the tunnel in the sewer after putting an end to Harry Lime’s (Orson Welles) life is what probably makes for the most iconic moment in the whole film, from the light reflected in the brickwork to the small stream of water that ends in Martins’ ghostly silhouette.