To be, or not to be?

Perhaps the most famous Shakespearean quote is the first articulated existential question. And here we are, centuries later, but nobody has ever answered this painful question for us‒ not even Friedrich Nietzsche, or Søren Kierkegaard. Not even Jean-Paul Sartre.

The total existential philosophical movement has been able to analyze our nature deeply and interpretively, answering a lot of longstanding introspective questions. Yet, this classic, dramaturgic, and archetypical query doesn’t correspond to a rational answer.

How often do you wake up with existential agonies? How often do you have that inexplicable pain in the stomach which shrinks your body and soul until your entire existence feels like a grain of dust dangling in the middle of an endless emptiness? Even when you get this feeling, even when the whole world seems to be meaningless and suspended, you’re not alone. The most significant humane conquests, like philosophy and art, exist due to such inherent feelings.

Definitely you know some of them. Maybe you’ve seen a couple of them. Most of these motion pictures move upon a black-and-white color palette. All of them are essentially character-driven. Anyhow, these 10 films discussed here talk about you. They reflect on the friends that you have and the friends you’ve lost. Don’t expect necessarily straightforward answers. But watch them if you mean to look in the mirror and ask yourself about your secrets.

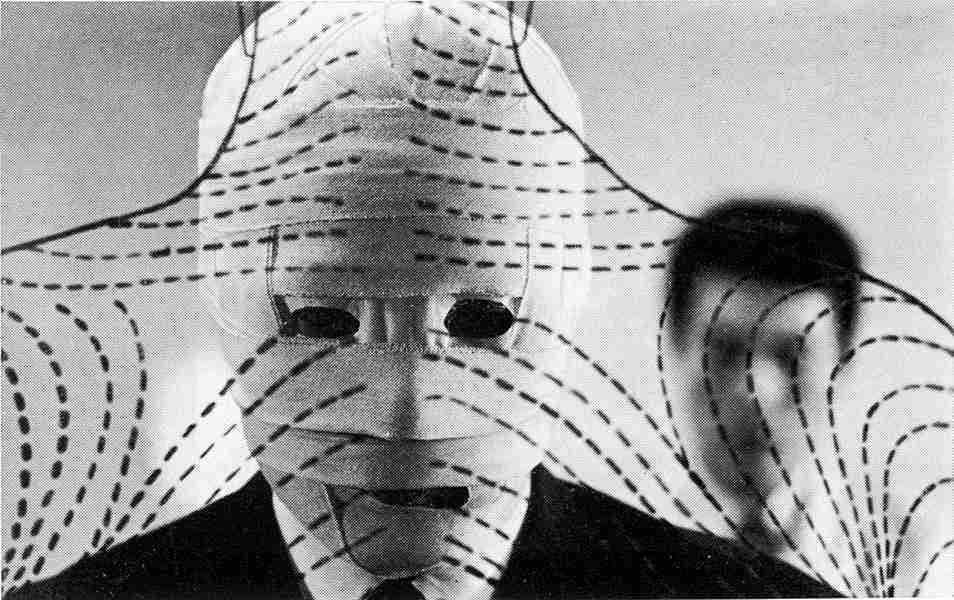

10. The Face of Another (1966)

Life begins in simple terms. Sculptured into specific shapes and structures, the miracle of existing and thinking introduces a granted self. Primarily, this self is expressed through a figure and is drawn on a face’s features. Later on, this face will mature and decay, but it will be just the same mirror of a character. Could you even imagine yourself without your face? This is the essential question posted in Hiroshi Teshigahara’s sci-fi existential film “Tanin no Kao.”

Okuyama is a victim of a horrid accident. His face has become completely disfigured due to an industrial fire. A team of doctors is able to restore his repulsive appearance by transplanting a new artificial face. After the operation, Okuyama beholds a stranger every time he looks in the mirror. And suddenly, he is a stranger in his own life; a stranger freed by the cumulative actions, experiences, and bonds of a lifetime.

As if he’s a restless ghost of a dead person, this unknown man walks through the crowd, spying on his wife. He makes love to her without revealing his identity. But is this Okuyama? Does he really feel like Okuyama? A man with the face of another observes his life from a distance and seeks to find out the way his old figure represented his mind, and most importantly, he seeks to find out where Okuyama is found, if not in his visible fingerprint. Chilling in an unconventional way, this cinematic gem explores the meaning of character, showing a remarkable apprehension of identity’s nature.

9. Memories of Underdevelopment (1968)

Tomás Gutiérrez Alea’s 1968 “Memories of Underdevelopment” seems like a collage of street photography portraits. Street photographers capture the spirit that lives behind arbitrary facial expressions and moving figures, allowing the constant flow of collective idealistic dynamics to survive on a frozen moment. Here, Alea does the same work in his own cinematic terms.

Cuba, 1962: A space-time setting that trembles between underdevelopment and revolution. Sergio is a privileged intellectual man who feels like trapped within this transitive window of history. His family and ex-wife have moved to the United States. He stayed in Havana, and decided to observe this repressed city’s attempts to conquer a real chance for its people. The revolution’s smell is spread all over, but the past’s overtone affects everything and everyone. A socially effective change can’t take place immediately, Sergio realizes.

Oftentimes, politics is about changes and changes are about politics. However, an essential change is based on a much deeper fundamental backdrop. In this fashion, “Memories of Underdevelopment” is on a first level about Fulgencio Batista’s and Fidel Castro’s Cuba, but substantially, is about its people: the ones who don’t want to change, the ones who try to do so, and the ones who don’t need to. Sergio envisions a changed world, reflected in the eyes of the people around him. Trapped in his personal existential trap, he abstains from that dream.

8. The Tree of the Wooden Clogs (1978)

In his socio-psychological work “Escape from Freedom,” Erich Fromm elaborates on the sense of security provided by an existence’s total control and domination by a sustaining external parameter.

By according a lifetime’s potentials and abilities of any kind to a superior force, one becomes an insignificant yet useful gear of a gigantic deterministic machine. Since the establishment of feudalism, the masses are incorporated in plundering systems. Poor people subliminally perceive themselves as sacrifices to a God’s worldly apparatus. Could the humble peasants of a feudal system imagine and uphold a heavier existential duty than that?

Obviously affected by the Italian neorealist film movement, Ermanno Olmi creates a persevering, observing, respectful, but still bothersome film about the real people of the past, for the people of his present. “The Tree of the Wooden Clogs” is an honest and detailing portrait of an Italian farming society during the 19th century. Owning less than the necessary, hoping for nothing more than surviving, unaware of pleasure, and constantly under the persistent eye of a closefisted and severe God, the story’s tragic human beings reflect on our past’s wholeness and on some of our present’s compounds.

How should life be? How could we be free? Are we really free? How much does freedom cost? “The Tree of the Wooden Clogs” isn’t a masterpiece. Perhaps it needed a groundbreaking ingredient so as to surpass the oblivion that followed a contemporary victory. But all of the aforementioned questions are painfully articulated over and over again in this story, not only for the projected miserable characters of a dead past, but for us: the contemporary citizens of a sparkly, expensive world.

7. Love Is Colder Than Death (1969)

Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s career was short but flourishing from many points of view. If you have watched several of his well-known and appreciated films, then his first feature is going to be a surprising experience. Fassbinder’s first fruit fuses his identifiable existential issues with an aesthetical synthesis inspired by the Nouvelle Vague. Since it’s a gangster movie, we could say that “Love Is Colder Than Death” is Fassbinder’s “Breathless.”

The great German director was 23 years old when he attempted to direct his first feature film as an independent promising artist. Of course, “Love Is Colder Than Death” isn’t his best film, not even one of his numerous best ones. It is, though, a steady first step into an ideologically, thematically, and artistically settled field. Original in its own way and marked by Fassbinder’s personal imprint, this debut film needs to be more illuminated and deconstructed into its fundamental qualities.

Franz is a young pimp. His days are haunted by another promoter’s demands, by the law’s constant cat-and-mouse game, and moreover, by his dysfunctional erotic relationship with a confusing prostitute. Here, for the first time, Fassbinder puts under a kaleidoscopic lens his own ignored and chased existence during his early life. He is Franz, and the film’s setting is his real territory: Munich.

Being neglected by every societal aspect, Franz seeks to survive in a hostile and apathetic environment. He seems to move within an amputated sphere of people who have imprisoned their own feelings and desires into a preposterous structure of dominion.

The film’s static close-ups and breezy black-and-white photography capture these self-made inner boundaries. But Franz longs for breaking free, it’s obvious. He just needs to love and be loved. Is this possible to happen, yet, in a place where love is colder than death?

6. 3-Iron (2004)

Based on a real artist’s sublime discernment and projected through an intelligent metaphorical script, Ki-duk Kim’s “3-Iron” is one of the most profound films ever made. A flat, conventionally rational analysis of the film’s plot isn’t just useless here, but completely disrupting as well. Tae-suk, the story’s surreal protagonist, is not actually a character: he’s an idea.

He’s solitary and silent. During the day he distributes commercial flyers, whereas he breaks into luxurious residences during the night. Surprisingly, his intentions steer clear from stealing, destroying, or killing. Living under the shadow of the residents’ absence, Tae-suk takes care of empty extravagant places.

One day, he finds out that a young woman has seen him living in her home, watching his routine calmly. She’s silent too, surviving under the shadow of her bleak life. From now on, she embraces his way of living, utilizing her mental and emotional potentials for the first time in her short wasted life. But their transparent flow in their world’s comforting corners can’t go on forever. He’s arrested for murder and she’s sent back to her abusive husband.

A concrete prison could never be a form of effective confinement for Tae-suk, since he’s the symbol of an utter spiritual freedom; a freedom that finds a territory in the absence of materialistic excess and overuse. Dedicated to all those who live in the shadows and stay ignored by the social complexes, and to all those who are indulged in the simplistic spiritual beauty, “3-Iron” is a unique interpretation of how we are and how we could be.