Amidst character development and storytelling which are considered to be the main ingredients for a watchable movie, visual style and precise direction are the main ones for a cinematic masterpiece. And since the seventh art is encapsulated for the most part in what meets the eye, here are some of the most wonderfully shot films with stunning visuals.

1. Mishima: A life in four chapters

Cinematographer: John Bailey

Paul Shrader’s 1985 biographical drama Mishima: A life in four chapters portrays the life and works of Japan’s most celebrated author Yukio Mishima. Author, poet, film director & nationalist, Yukio Mishima is unraveled through Shrader’s lens.

The exclusivity of Mishima’s narrative lies in the dichotomy between human & author that Shrader cleverly constructed. We first get to experience the persona in whose name the film is founded, just like in a typical biopic. However, shortly the dramatizations of Mishima’s most famous works come on screen.

The potential confusion that may arise from this is obvious: Biographical drama or book adaptation? And the answer, is biographical drama, from the beginning to the end. With the clever narration trick of presenting Mishima and his complex ideas through his works, which are embedded in the film reflect him.

Additionally, Mishima’s impressive cinematography and style is inimitable. The perfect geometry that consumes the majority of the frames, the use of saturated colors and the scenic depictions of Japan constitute the aesthetics of the film unique in the exact same way as Yukio Mishima’s works, blending beautifully modernity and tradition.

The film starts with Mishima’s last day alive and proceeds to a throwback in his early years as a sickly boy and his transformation to an acclaimed author and later on extreme traditionalist. The dramatizations that follow depict three of Yukio Mishima’s most celebrated novels: The Temple of the Golden Pavilion, where a man sets fire to a Buddhist temple, Kyoko’s house, where a young man is in financial debt to his middle-aged lover and Runnaway Horses, where a group of fanatic nationalists commits seppuku after failing to overthrow the government.

2. Kill Bill : Vol 1 & Vol 2

Cinematographer: Robert Richardson

No need for introductions to this one. Tarantino’s 2004 martial arts/ spaghetti western/ revenge drama film “Kill Bill” has become a cult classic. Tarantino plays the cool & badass card again and this is certainly the most profound reason for which “Kill Bill Vol 1& 2” have both found a permanent spot in every cinematic heart.

And aside Tarnation’s obsession and success with witty dialogues, killer soundtrack and original screenplay, “Kill Bill’s” greatest triumph is its visual style. Less witty dialogues than in “Pulp Fiction”, less psychographic depth into the characters than in “Inglorious Basterds”, and more graphic violence than in “Reservoir Dogs”. “Kill Bill” is what notoriously established the anesthetization of violence as Tarantino landmark.

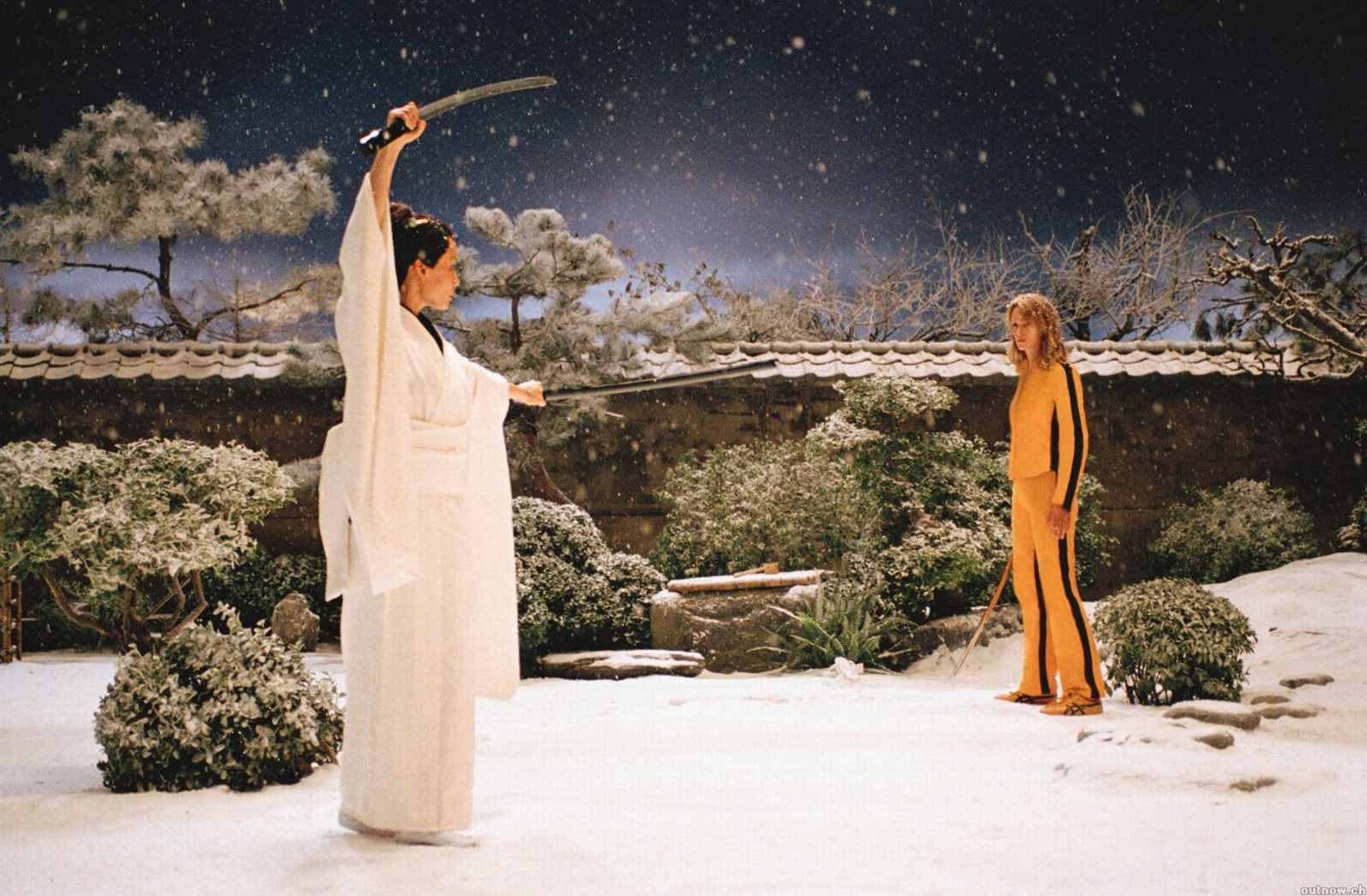

The beautiful roughness and vulgarity of “Kill Bill” surpasses that of every other Tarantino film and is certainly inimitable. What constitutes the atmosphere of “Kill Bill” so one of a kind is the mixture of Samurai/cowboy which Tarantino beautifully portrays in four hours of film that follow the protagonist, “The Bride”, in her journey.

From a red wedding at “El Paso” to a hostile hospital and then to Okinawa in search of a deadly weapon and back to rural America in search of revenge. The multitude of different cultural elements and styles of shooting inspired by Japanese gore, spaghetti western and film noir as well as the references to those sources of inspiration (The Bride’s iconic yellow and black suit is worn by Bruce Lee in “Game of Death”) give “Kill Bill” its one of a kind vibe that cannot be copied.

3. Three Colours: Red

Cinematographer: Piotr Sobociński

Krzysztof Kieślowski’s Red, the third film in his posthumous Three colors trilogy follows Valentine ( Irene Jacob), a university student that works as a part-time model. Valentine is the face of a chewing gum campaign and during her time at the studio, a sad looking picture of her is selected for the campaign, which becomes a recurrent image of the film. Valentine runs over the dog of her withdrawn and voyeuristic neighbor ( Jean-Louis Trintignant).

The incident makes their paths cross and through conversation Valentine discovers that the lonely man is eavesdropping on the phone the conversations of all of his neighbors. In the same neighborhood, an aspiring judge, Auguste ( Jean- Pierre Lorit) loves a woman who betrays him. His present situation is a deja vivre of what has happened to Valentine’s lonely neighbor long ago. The kinships among the three characters are explored throughout the film.

Red is certainly the most iconic and loved feature film of Kieslowski’s three colors trilogy. Its most overarching visual element is certainly the deep red that encircles the majority of frames and creates strong emotion and tension. What is striking is the melancholy that oozes and contrasts the supposed warmth that results from Kieslowski’s recurrent red palette.

4. The Conformist

Cinematographer: Vittorio Storaro

The Conformist is Bertollucci’s most stunning directorial work. A film about convention and conformism achieves excellent aesthetics, which are in perfect alliance with Bertollucci’s themes. Vittorio Stotaro’s camera work in The Conformist is so encapsulating of Bertollucci’s vision that it manages to convince the viewer of the reality and ease with which one complies, even with the most atrocious regimes.

The perfect symmetry and repetitiveness along with the grey palette use which subtle beams of light illuminate make the frames as rigid and unforgiving as fascism itself. In The Conformist the miserable and sterilized scenes end up conveying a surprising beauty and elegance because of their accuracy and perfect congruence with the emotion the film ought to induce.

Marcello Clerici ( Jean-Louis Trintignant) is a submissive man and fascist sympathizer who agrees to kill his college professor, a political refugee that is wanted dead by the fascist government. His fiancé ( Stefania Sandrelli) asks him to confess before their marriage, which he does despite being an atheist.

Marcello admits his indifference towards his wife to be but admits to a desire for a conventional and normal middle-class life. His efforts of obtaining it are witnessed through his appalling actions of compliance and absolute lack of guilt. But despite Marcello’s attempts, his hidden secrets and inner deviance from what the establishment deems acceptable may be the very reasons he feels so desperate to conform.

5. The Tree Of Life

Cinematographer: Emmanuel Lubezki

Terrence Mallick’s 2011 cosmological epic drama earned him the Palm D’Or at Cannes film festival as well as the critics’ respect, however it did not receive the affections of audiences. This isn’t surprising since the film is characterized by a slow pace, a 139 minute length (and that’s only the theatrical release) and long extracts depicting the birth of the universe and our solar system. Despite its difficulty, The Tree of Life is undoubtedly a success and most importantly an immense cinematographic achievement for Emmanuel Lubezki.

The film follows the childhood and adulthood of Jack O’Brien (Sean Pen), a disillusioned architect and the eldest son of a family of five. His complicated relationship with his father (Brad Pitt) is unraveled through flashbacks dating from birth to current age. In between dramatizations, space sequences, volcanic eruptions and microbes that replicate are depicted.

What Mallick and Lubezki crafted in The Tree of Life doesn’t look like anything else. The film is a creationist drama, telling its story, from the beginning, the genesis of the cosmos and then transcends to the lower levels of its separate beings in order to focus in the lives and development of its characters.

The parts that depict the formation of the galaxy and the earth are so silent and lengthy – especially throughout the first half of the film- that the viewer often forgets the existence and story relevance of the protagonists that the film follows, which might have been Mallick’s exact intention.