The most famous director to ever come out of the Soviet Union, Andrei Tarkovsky has had a massive influence on both auteurist filmmakers and the science-fiction genre. Known for his long and austere takes, serious inquisitions into the nature of the human spirit and enigmatic endings, his relatively short filmography — spanning only seven features — is easily one of the best of all time.

But what if you have seen all of his films and are in the mood for more moody dramas about the impermanence of life and the impossibility of connection, shot against a bleak backdrop of decay or nostalgia?

We have the perfect list for you. Covering both the Russian and Soviet filmmakers who related to and were inspired by his style to mainstream Hollywood cinema and the wider global auteurist scene, this eclectic list is the perfect showcase of what Tarkovskesque film is outside of the great man himself.

It shows that the director is not somebody who can be easily put in one box or another, but someone with a variety of techniques and themes that is one of the most diverse in cinema. Think we missed anything important? Give us your suggestions in the comments below.

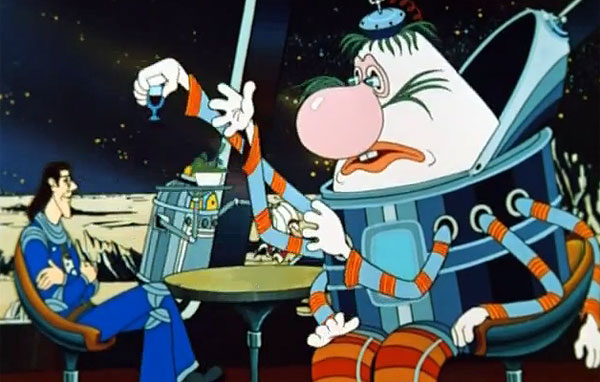

1. The Secret of the Third Planet (Roman Kachanov, 1981)

A true Russian cult classic, The Secret of the Third Planet is a traditionally animated tale based upon the novella by children’s writer Kir Bulychev that shows the best of what Soviet science fiction can do. While light, bouncy and colourful where Tarkovsky’s two science fiction outings Solaris and Stalker were dark, austere and brooding, both The Secret of the Third Planet and those two films have the same fascination with uncovering the unknown.

Produced by the Soyuzmultfilm studio in Moscow, it tells the story of a space crew on a mission to find new animal species for the city’s zoo. Along the way they discover all sorts of strange creatures, ranging from talking birds to flowers that act as mirrors to strange floating jellyfish.

While ostensibly a Yellow Submarine-style children’s tale about exploration and discovery, its boundless imagination easily asserts it as one of the most memorable animated science-fiction films to come out of the Soviet Union in the 1980s.

2. Kin-dza-dza! (Georgiy Daneliya, 1986)

A truly bizarre science-fiction tragicomedy that doubled up as a critique of the absurdity of the Soviet regime, Kin-dza-dza! was Georgian director Georgiy Daneliya’s biggest hit.

Similar to how the search for the zone in Stalker was a metaphor about the search for meaning in a fractured society, the desert planet of Kin-dza-dza! is the Soviet Union through the looking glass. While approaching their material in very different ways — and Kin-dza-dza! is remarkably silly, even by Daneliya’s standards — both directors utilised the sci-fi genres to hide broader critiques about the Soviet Union.

It tells the story of two Muscovites who suddenly find themselves transported to a strange land. There they encounter a society governed by completely bizarre rules. As funny as it is satirical, it showed Daneliya at the height of his tragicomic powers.

Never breaking out of the Soviet Union apart from a small release in Japan, Kin-dza-dza! is the true definition of a cult film. Basically begging a rerelease, its shows that Soviet science-fiction went to far stranger — and funnier — places than just Stalker and Solaris.

3. Hard to Be a God (Aleksei German, 2013)

Legendary Soviet director and contemporary to Andrei Tarkovsky, Aleksei German had a torrid time getting his films off the ground during the communist era. Both directors were deeply harmed by censorship, making one wonder what could’ve been if they were allowed to carry on uninhibited.

His sixth and final film, Hard to Be a God is German’s masterpiece and shares direct similarities to Stalker. Both films are based on novels by co-writers Akardy and Boris Strugatsky, science-fiction authors whose works were characterised by a highly intellectual and philosophical bent.

Hard to Be a God tells the story of scientists who travel to a nearly identical alien planet which is stuck in the middle ages. One scientist assumes the persona of Don Rumuta, a nobleman living in a castle. There he comes into contact with a completely and backwards world.

Darker and more grotesque than any of Tarkovsky’s visions — which although obsessed with falling textures such as rain and snow were generally quite uncluttered — its slow pace and science fiction theme makes Hard to Be A God one of the best Russian films of the past ten years.

4. Loveless (Andrey Zvyagintsev, 2017)

If any modern living Russian director was to assume the mantle of Tarkovsky’s successor, the eternally depressing Andrey Zvyagintsev is the closest heir (after Aleksey German Jr). His films are slow and melancholic, characterised by long, looping tracking shots and characters seemingly shut-off from expressing positive emotions.

His latest film, Loveless, telling the story of two bickering parents who don’t notice when their child has gone missing, is a great case in point, using the metaphor of a lost child to comment on the state of Modern Russia and the country’s controversial conflict with Ukraine.

While not quite as pointed as the work of Ukrainian director Sergei Loznitsa, Zvyagintsev’s latest film is a no-holds-barred critique of a country that has seemingly lost its way.

Made with international support after the government was less than pleased with his anti-corruption tome Leviathan, Loveless is characterised by its bleak portrayal of Moscow as a land without hope or love. Alternately moving, intimate and dark, its tragic landscapes bring to mind Nostalghia and The Sacrifice. It’s not an easy film to watch, but rewarding in spades.

5. Come and See (Elim Klimov, 1985)

One of the definitive anti-war films, Come and See can be directly compared to Tarkovsky’s first feature Ivan’s Childhood. Telling a Second World War story through the eyes of a child, Come and See is a harrowing depiction of the brutal cost of war.

Telling the story of a young Belorussian teen who joins the resistance against the Nazi occupation, it portrays a complete descent into madness and despair. A direct inspiration on Steven Spielberg — who screened it before starting both Schindler’s List and Saving Private Ryan — it is the true heir to The Cranes are Flying in the way that it marries anti-war concerns with bravura filmmaking.

Ending with a dash of inspiration that figuratively moves backwards in time, it truly counts the cost of the most terrible war of all time. Accompanied by a brutal score by Oleg Yanchenko, Soviet Marching songs and classical music such as Mozart’s Requiem and the Ride from Wagner’s Die Walküre, Come and See is one the rare 80’s Soviet films that has become required viewing across the world of cinema.