Cinema sometimes is a shadow of thoughts carved in the pathway of its creator’s steps through life. Cinema is both science and magic. Cinema, in its purest form, is a reflection of beauty and ugliness into shapes and shades that stain one’s mind in their sincere illustration.

In Ingmar Bergman’s shattered subliminal terrors, we’ve loved cinema’s secret ingredient which flows in our trembling veins. On Andrei Tarkovsky’s hovering ghosts of memory, we’ve always loved cinema’s direct capability of mental interpretation. We are all movie buffs, at the end, and what keeps our minds stimulated is cinema’s highest purity as it occurs on visual moments of recorded human intelligence.

The cases of cinematic mastery captured in a scene’s exposition are numerous. This is just a selection of 10 scenes and sequences that showcase technical glory, visual beauty and substantial adequacy. Let’s enjoy them.

10. Memories of Murder (2003) – They’re watching in the rain

Based on real events that took place in South Korea in the time span of 1986-1991, Joon-ho Bong’s 2003 “Memories of Murder” tells the abominable story of a serial killer who always used the same eccentric techniques so as to abuse his female victims, as it was experienced and handled by the local community.

Obsessed with rainy days, red clothes and one specific pop song, the film’s dark criminal managed to create a vivid reflection of his character in his seekers’ eyes and remain under the shadow of his pitch-black intelligence all the same.

Bong’s cinematographically ravishing interpretation of a serial killer case deals with many issues, instead of strictly focusing on the mystery’s effect on the viewer. The film’s thematic center is rendered on a sickly social framework that strangles human liberty, as it also highlights the aspect of the investigators who are ethically and sentimentally involved in the case. A dispersed mood of climactic mystery dresses the story’s solid core as an embellishing cloth that doesn’t steal any of its substance.

In the most fascinating sequence of the picture, the detective team has prepared a well-studied ambush to the killer. The rain begins. A female detective wears a red dress and walks in the woods. Her colleagues wait in an observatory. The real victim, though, is all alone. She looks around…

Then, a phone rings. This sequence is masterfully synthesized, bringing out the killer’s unbeatable plan. We believe we can read his mind and then we find out we were trapped. In its unparalleled operation, this compilation of events represents an aspect of cinema’s skill to influence.

9. Enter the Void (2009) – Opening sequence

The loved and hated enfant terrible of “New French Extremity” has fearlessly dived into the muddy waters of a both real and elusive underworld, dragging up familiar, sometimes detestable figures that were sculpted by the hands of a relentless master. Gaspar Noé looks his miserable creatures directly in the eye, as he simultaneously exposes them at the day’s burning light and at his own love’s warmth.

Among his shocking, visually explicit and still deeply dramatic works, “Enter the Void” is defined by the most delicately existential texture. Its plot involves two American siblings, a male drug user and a female stripper, who carry their sorrowful minds in the cosmic maelstrom of modern Tokyo. Oscar narrates the story through the delirious cerebral paths of his drugged mind until he finds a way to hover over his former existential void of wounds and griefs.

The notorious opening sequence of the film introduces us to a world of persistent flashing lights that encircle a gloomy territory of tarnished souls. Oscar is the point of observation, as his eyes seem to film his balcony’s view during the usual routine of getting high. His perspective provides an imagery as psychedelic as sadly deforming, directly delivering the hero’s mental state and engaging the viewer to the story’s psychological landscape. Intoxicating and depressing at the same time, this is one of Noé’s greatest cinematic moments.

8. Dreams (1990) – Kurosawa walks on a Van Gogh’s painting

One of cinema’s greatest possibilities is the depiction of that fleeting breath of hidden thoughts that we call “dreams.” We admired this ability on Andrei Tarkovsky’s oneiric mirrors. Then, we experienced its chilly effect in David Lynch’s surreal dream world. In Akira Kurosawa’s 1990 “Yume,” more directly than ever, we saw his own nocturnal voyages in a land of childhood idols and adulthood terrors.

From his days of puerility until his years of conscious maturity, the Japanese auteur experiences a meandering in his most beloved places and in the most dystopian infernos of an almost collapsed real world. Every viewer of this film makes a plunge in Kurosawa’s conscience, which is generously drawn on a canvas of bewildering visual beauty and contextual profoundness.

Perhaps the most striking part of the film involves a dream of Kurosawa about Vincent Van Gogh’s art: He carefully looks at a painting in a museum and suddenly, the depicted landscape absorbs him.

Accompanied by Fredric Chopin’s engaging music, Kurosawa walks on the painting’s textured alleys of mixed color, until the entire landscape becomes real. Kurosawa follows Van Gogh in the territories that hosted and inspired him, and eventually reflected his artwork. This is one of the greatest co-existences of two legendary artists in the cinematic universe.

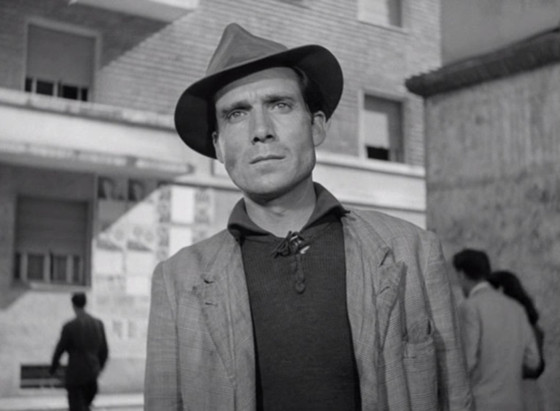

7. Bicycle Thieves (1948) – Antonio’s attempt to steal the bicycle

One of the most representative pieces of the Italian Neorealist Movement and diachronically one of the best pieces of the seventh art generally, Vittorio De Sica’s “Bicycle Thieves” captures the quintessential morbidity of the societal circumstances in post-war Italy, in its sincere simplicity. As if letting all of the parameters flow in a naturalistic circular course, De Sica sheds some light on a realistic figure that could have suffered in a similar way uncountable time.

This time, it was Antonio. He just needed a job so as to provide food and shelter to his little boy. His attempts were many and the offers were few, while his son’s needs were daily intensified. Finally, a job would be offered him, as long as he owns a bicycle. And yes, he owns a bicycle, until it’s stolen. What is he supposed to do now? How can he claim a weapon to survive? Why should his fate be so relentless?

Existing in the small void of space that lies between struggle and pauperism, Antonio can’t find an honest way to save his family. He has to steal a bicycle. In the wrecked structure of his city, perhaps a bicycle is more valuable than human life. He doesn’t mean to harm anyone. He despises the act his hands are about to commit, but he just has to live. In these few moments before Antonio grabs the bicycle, we observe a desperate dance of an ignored, unfairly impoverished human being.

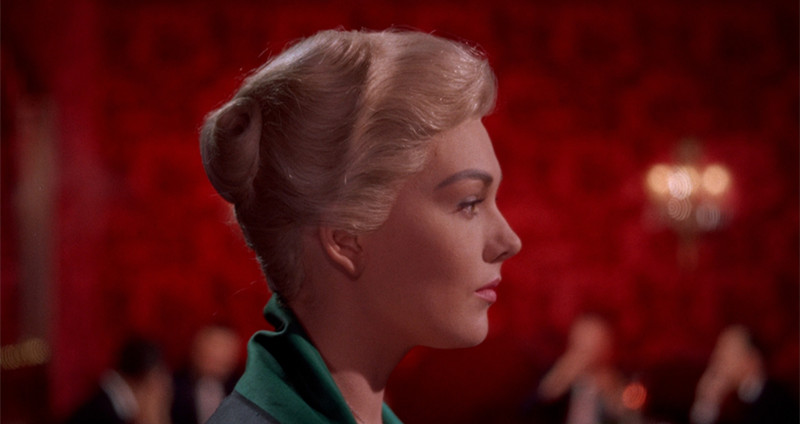

6. Vertigo (1958) – The revelation of Madeleine Elster

Lying among Alfred Hitchcock’s best works, the 1958 American classic “Vertigo” is a skillfully composed symphony of charged moments. The maestro of thriller-mystery film genre really knows how to prove that mundanity creates illusion and illusion reflects mundanity all the same on the deceiving glass which stands between them. James Stewart as Scottie Ferguson is Hitchcock’s quintessential character and Judy Barton is just a woman disguised in his dream’s lace.

Scottie is a man of both fragile body and mind. He suffers from fear and pain. He even bears an insistent feeling of loneliness. When a woman called Madeleine Elster is introduced to him, he beholds his dream in flesh and bones. Dressed in expensive fabric and embellished by her shiny blonde hair, Madeleine is just a retouched image of a less glowing woman. Eventually, Scottie finds out he was trapped, but he’s not ready to let his dream disappear in the abyss of nonexistence.

The meeting of Scottie and Madeleine takes place during one of the most iconic shot sequences in cinema history. Indeed, the combination of camera movement, perspective, color synthesis, and body movement provides a very well-crafted scene that accurately serves the film’s contextual framework.

Scottie stands at the bar. Madeleine is found somewhere among other people in the background, but her figure is dressed in green while the walls have a bright red color. She walks toward Scottie while following coordinated moves, their eyes cross. Then, she moves back again. Before she exits the room, her figure is reflected in a mirror…