Discussing Buddhism can be a tricky task; after all, the first rule of Enlightenment is: you do not talk about Enlightenment. The essence of awareness is the living of it, and the one who loudly claims to understand the nature of reality has not understood it. Still, from ancient times Buddhism has used stories to illustrate ideas and point to truths, and so a film about the venerated religion may also be a profitable subject for study.

The ideal Buddhist film would perhaps possess the qualities of a koan – asking a question for which there is no logical answer. “What is the sound of one hand clapping?” is one of the most famous examples of a koan; of course the riddle is paradoxical, and against its brick wall the human reasoning faculty struggles until finally (hopefully) resting from the fight and transcending itself. But even these profound anecdotes have their limits: Enlightenment cannot be owned, and therefore it cannot be given. All the teacher can do is ask the question which points toward the promised land, which the student must explore alone.

Here are ten films which in some way embody aspects of Buddhist thought, and which ask important questions of the viewer. Dogmatism and easy answers are not to be found in them, but each is a thoughtful, provocative invitation to meditation.

Some of the films directly relate to the history of Buddhism and its important figures; others are inspired by the noble truths which adorn the path to personal liberation. All are meant to be viewed with care and attention. As always, the most important lessons in life cannot be taught, but only learned; therefore, they cannot be advertised, but only recognized. In these films, thoughtful viewers may find their own lives reflected in instructive ways.

1. Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter… and Spring (2003) – Kim Ki-duk

On a floating monastery in a beautiful lake, a young Buddhist monk and his master live their austere, simple lives in Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter… and Spring. This film traces the life of the young monk as he grows into adulthood and old age, with each stage of his life represented by a season of the year.

The wise master oversees the boy’s training with the kindness and patience of a parent, using the child’s failures and successes to teach valuable life lessons. But when the teenage boy falls in love for the first time, his carefully planned circle of life is threatened with disruption.

This film perfectly exemplifies Buddhist teaching and ideals in both its narrative structure and its message. By framing its story within the changing seasons of the year and of life, it reminds us of the impermanent yet recurring nature of each stage of existence.

The great Gautama Buddha sought to help people understand why they suffer and how they can end their suffering: “All conditioned things are impermanent – when one sees this with wisdom, one turns away from suffering” he said.

Likewise, the master in Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter… and Spring knows and seeks to teach his student that the importance of every season should be embraced without attachment. Siddhārtha Gautama taught that by maintaining the proper perspective and welcoming each change in one’s life, we may avoid the sorrow that comes from clinging to either the joys or sorrows of any given season, and thereby achieve balance.

2. Why Has Bodhi-Dharma Left for the East? (1989) – Bae Yong-kyun

It’s difficult to think of a film that more completely embodies the spirit of Buddhism in content and style than this unique classic. The director, a professor and painter, made this film with one camera over the course of seven years. His dedication is revealed in the small details of this beautiful movie, which show extraordinary care and forethought.

With minimal dialogue, Why Has Bodhi-Dharma Left for the East? unfolds on screen as naturally and subtly as life itself. There is no attempt to hammer home its message or explain the inexplicable, but rather the lessons of the film are demonstrated through the story itself.

The film traces the lives of three Buddhist monks at different stages of life: a young orphan boy, an adult monk, and an elderly Zen master. The plot unfolds as naturally and gracefully as a flower, and exemplifies karma and the meditative state effortlessly. It’s a truly unique film experience, and worthy of repeated viewings.

The koan plays a valuable role in Buddhism, and is an extraordinarily effective teaching device. Often framed as a story or a question, a koan is a difficult concept for the rational mind to process, and its purpose is to provoke doubt or further spiritual inquiry. The title of this film is itself a kind of koan, and the story functions as an extension of the titular questions which the viewer may consider throughout. Bodhidharma, who is mentioned in the question, was an Indian monk who brought Zen Buddhism to China many centuries ago.

Within the film, two additional koans make up critical aspects of the plot. The first is “What was my original face before my father and mother were conceived?” The second is “When the moon takes over in your heart, where does the master of my being go?” These questions are at the heart of this wonderful film, and the answers await exploration by the thoughtful viewer.

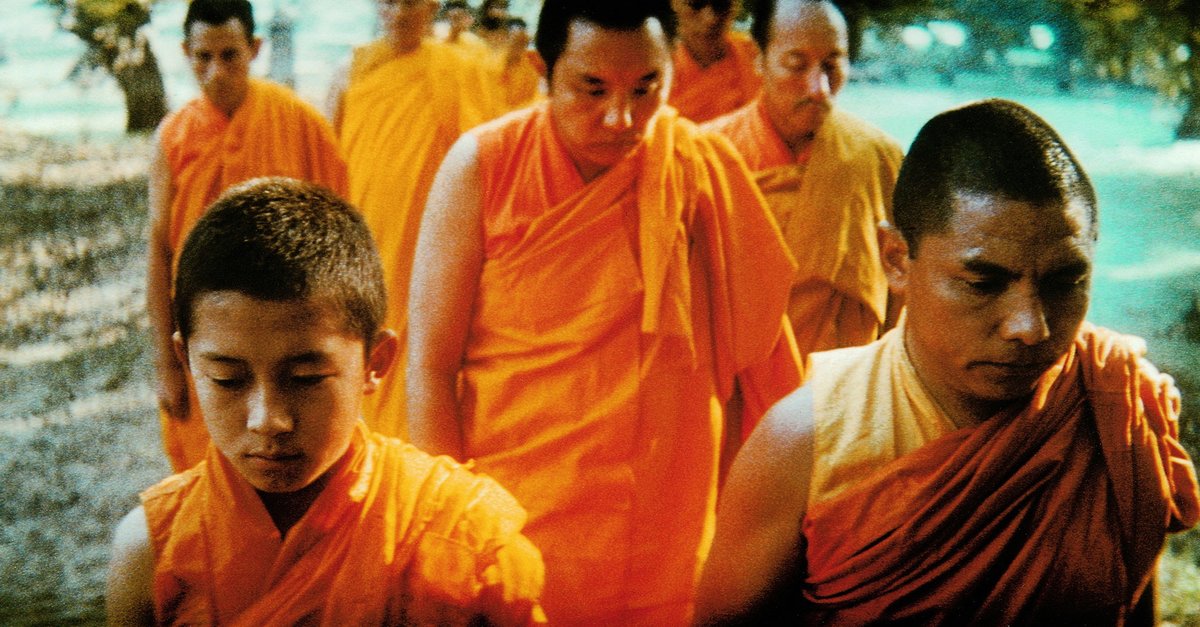

3. Kundun (1997) – Martin Scorsese

Martin Scorsese’s epic film is a straightforward but inspired telling of the life of Tenzin Gyatso, the 14th Dalai Lama. The leader of Tibetan Buddhism has simultaneously served as a universal ambassador for the religion as a whole, and his personal appeal and charisma are legendary. While Kundun is no hagiography, it is a respectful biopic which allows the viewer to experience the film as a meditation, and its affection for its subject is infectious.

The writer, Melissa Mathison, met with the Dalai Lama to ask his permission and blessing for her project, and received both; she proceeded to conduct interviews with him, which eventually formed her script. The brilliant soundtrack by Philip Glass enhances the meditative quality which Kundun possesses, and helps to make this film experience a delight to lose oneself in.

The legendary Roger Deakins served as cinematographer for this extraordinarily beautiful film which perfectly serves the spirit of its subject. Kundun provides a detailed account of how an iconic world figure became who he is, and anyone who has seen the smiling face of the adult Dalai Lama will be fascinated by his life’s story.

“Kundun” is one of the titles by which the Dalai Lama is addressed, and the word means “presence.” Each Dalai Lama is believed to be an incarnation of the Bodhisattva of Compassion which manifests according to the needs of a given generation. In Buddhism, a bodhisattva is one who taken the necessary steps to achieve nirvana, but chooses to delay entering that state out of a deep desire to help other beings who continue to suffer.

Having extinguished the fires of desire and ignorance, a bodhisattva nevertheless remains within the cycle of rebirth with the express motive of compassion for those who remain in darkness and pain. The 14th Dalai Lama has played a significant role in many important events of the 20th century, and his story is one worth exploring through this excellent film.

4. The Burmese Harp (1956) – Kon Ichikawa

Mizushima, the protagonist of this Japanese film, is no coward; he has proven his bravery in battle, but circumstances have forced him apart from his unit. Narrowly escaping death, our hero along with his beloved harp begins the quest to rejoin his friends; but the death and destruction which line his path will change his life forever.

As Mizushima is confronted with corpse after corpse of once hopeful and promising young men, he feels compelled to give them proper burials. Losing himself in this higher purpose, he finds that the Buddhist ideals he is embracing could keep him separated from his comrades and his home until his work is done. We are asked to consider: do enlightenment and integrity require removing oneself, psychologically or physically, from the corruptive influences of a society? Our friend, armed with his harp and song, will have to make a difficult decision.

“It is no measure of health to be well adjusted to a profoundly sick society.” One can imagine the great teacher Jiddu Krishnamurti giving this advice to Mizushima, for this is the realization the young man makes on his path to enlightenment. While this story shows the atrocities of war, it is more than an anti-war screed (does not fighting against war make hypocrites of the opposition?); rather, it is advocating a more transcendent response to societal evils.

And some response is indeed called for by the principles of Buddhism; the inner harmony which is the culmination of its teachings and practices should never be confused with conformity. Only by acting in complete accord with the precepts of peace can one remain on the path which is as narrow as the razor’s edge; whether or not that path leads to moments of social isolation is not an important question.

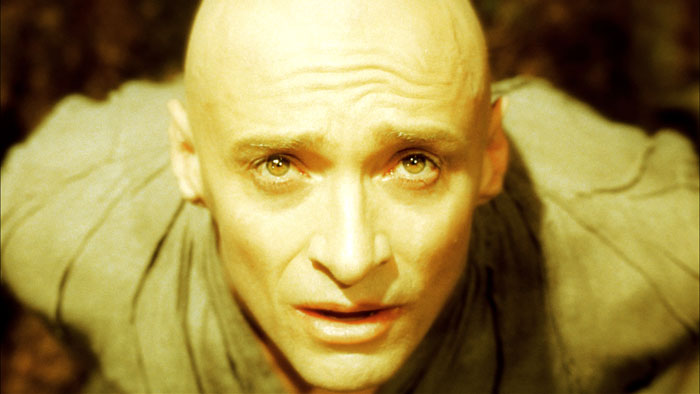

5. Siddhartha (1972) – Conrad Rooks

Siddhārtha is another name for Gautama Buddha, the individual on whose teachings Buddhism was founded. This film, which relates the details of his life as we know them, is based on Herman Hesse’s novel of the same name. The book Siddhārtha is one that many people stumble upon during the course of an education, but this screen version breathes new life into the beloved tale.

Alongside the legendary cinematographer Sven Nykvist, director Conrad Rooks filmed Siddhārtha in Northern India, where the original events are said to have taken place. It’s a film that adheres closely to the content of the written version, but the gorgeous visuals enhance the transcendent feel of the fable in a special way. For anyone who remembers the book fondly, and for those who are unfamiliar with the story of Siddhārtha, this film is essential viewing.

A central tenet of Buddhism is the idea of living according to a “Middle Way,” which describes the nature of the moral path one should follow. Gautama Buddha chose this Middle Way for himself, and subsequently made it one of his primary teachings.

The film Siddhārtha details how he arrived at this balanced choice for his own life, and shares the experiences which shaped this core belief. Throughout religious history, the practice of asceticism, or severe self-discipline, has been a point of intense debate; some consider such austerity as mandatory for spiritual growth, while others view it as a hindrance.

While the contrasting practice of hedonism, or self-indulgent pleasure, is less often favored by religious practitioners, it remains a preferred way of life for many. Siddhārtha passed through periods in which he tested the waters of both austerity of pleasure, and came to believe that the proper path rested between the two extremes. This Middle Way was the one which Gautama Buddha’s own enlightenment taught him to follow, and it remains the Buddhist ideal.