Though the arrival of Jean Luc-Godard’s Breathless in 1960 is an undisputed breakthrough moment in international cinema, New Wave movements do not end (or necessarily start) in France.

In the days and decades following frequently cited Nouvelle Vague films like Breathless and François Truffaut’s The 400 Blows, dozens of countries have exploded onto the world stage with approaches to the medium that are difficult to clump together, other than by way of their shared experimental nature and the fact that the majority of New Wave directors have a deep knowledge of film history.

In 2019, as social media continues to link the world, it grows more and more enticing to stay inside, and cultural movements as unanimous as a Nouvelle Vague or Cinema Novo are harder to come by. These 15 films, starting with the forefather of arthouse cinema, all speak to the history and empathy that can come from a deep dive into another country’s cinematic history, and often times, it all starts with a wave.

1. Pather Panchali (from The Apu Trilogy) by Satyajit Ray (1955)

India, Parallel Cinema

By the early 1950s, the through-a-window realism of Indian Cinema’s early filmmakers had been all but destroyed by the song-and-dance success of a cinematic movement based in Mumbai: Bollywood. As the earliest film on the list, it is appropriate that one of the first New Waves established in cinematic history was a response to maybe the most lavish, melodramatic, and commercial (to this day, Bollywood produces the most films per year of any industry) mainstreams.

As a response to the rise of international arthouse festivals like Cannes, the Indian government set out to finance films that, unlike those produced in Bollywood, would be critically successful. The filmmakers who defined Parallel Cinema are Mrinal Sen (The Calcutta Trilogy), Ritwik Ghatak (The Cloud-Capped Star), and Satyajit Ray.

Adapted from fellow Bengali Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhay’s novel of the same name, Pather Panchali, the first in The Apu Trilogy, originally premiered at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City in 1955, after three years of production on a shoe-string budget. Even without subtitles, the film’s careful attention to childhood and the beauty of wonderment made it a splash at Cannes and beyond.

Put simply, young Apu Roy’s (Subir Banerjee) sole goal throughout the film is to see a train. Rarely does Apu say a word (though his milky eyes say millions), but Ray places a lot of value on Apu’s pursuit of simple joys by framing it as an escape from his family’s many struggles. Durga (Uma Dasgupta), Apu’s older sister, has unfortunately been relegated to a life of work, as her father is often off working and her mother Sarbajaya is responsible for, well, the billion jobs that comprise motherhood.

When Durga picks up fruit off the ground from a neighbor’s orchard (which used to be the Roy family’s, before they had to sell it for money to repair the house the buyers helped destroy), Sarbajaya pulls her hair and drags her through the mud. The magic of the film lies in the way Ray gently guides us away from jumping to any conclusions, following up this violence with a monologue from Sarbajaya about the dreams she had to give up for her family.

Karuna Banerjee’s performance, punctuating every dark moment with facial expressions of helplessness and anguish, is perhaps the most pivotal in the film, as Abu is only a young boy in this installment of the trilogy. Even though the cycle of violence trickles down via Durga beating her brother for borrowing foil from her toy box to make a mustache with, seeing how disadvantaged she is compared to her friends makes it hard to feel anything other than love for her.

Famously, François Truffaut was not (initially) impressed, walking out of the film because he didn’t “want to see a movie of peasants eating with their hands,” before modeling what is commonly considered the start of the Nouvelle Vague, The 400 Blows, and its successive quadrilogy, on the movie. This, perhaps, is one of the reasons why Agnes Varda is on the list and not him.

This, perhaps, is the reason why it might be more appropriate to consider the Parallel Cinema the world’s first “New Wave” movement. Oh, and we have cinematographer Subrata Mitra and his work on the trilogy to thank for bounce lighting. Thanks, Mr. Mitra.

Available on Kanopy.

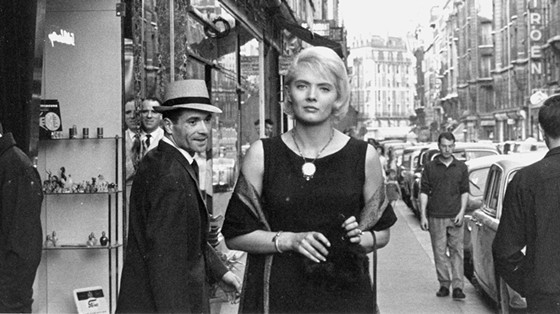

2. Cléo from 5 to 7 by Agnes Varda (1962)

France, The Nouvelle Vague

It would probably be unnecessary to discuss in too much detail here the key figures of the French New Wave, the iconoclastic spirit of the movement as a whole, and its lasting impact on international cinema.

In short: Agnès Varda, her husband Jaques Demy, and their contemporaries made films that questioned the long-established conventions of cinema as a medium, setting out to make as many films as possible, from off-beat musicals to crime pictures littered with jump cuts, that defied notions of genre, style, and even the relationship between film and audience.

Some of the eminent figures of the period, including Godard, were accused by critics of having some sort of contempt for the audience, operating like surgeons tasked with dismantling film rather than the art of storytelling. Such a classification could not be further from the truth when describing Agnès Varda, and her warmth is characteristic of the Nouvelle Vague subset, The Left Bank.

Cléo from 5 to 7 followed Ms. Varda’s debut feature La Pointe Courte, a micro-budget film comprised largely of unprofessionals that preceded Godard and Truffaut’s debut by four years. Fun fact: it was also co-edited by Hiroshima mon amour director Alain Resnais.

Though widely regarded as a classic, La Pointe Courte made no money and relegated Varda to directing shorts and government-funded documentaries for the next seven years. The time spent working on her craft is obvious in her follow-up. Cléo starts with a lie: while the film’s title suggests (and “suggests” is generous) that it will follow two diegetic hours of the protagonist’s life, it is really an hour and a half.

This is Varda’s big lie, perhaps hinting at the way every man that Cléo (Corinne Marchand) talks to in the film thinks she is lying about her cancer diagnosis, which is seen on-screen. After coming home from the doctor’s office, Cléo’s maid Angèle (Dominique Davray) warns her “don’t say you’re ill, men hate illness.” Unfortunately, it turns out that the men she meets— including soldiers, artists, musicians, don’t just belittle ill women, they entirely dismiss the possibility of there being such a thing.

Soundtracked by nouvelle chanson songs sung by Cléo herself (and written by the late great Michel Legrand), a pop singer, the film investigates the oppressive structures that render Cléo obsessed (“as long as I’m beautiful, I’m alive” she says early on) and devoid of self control. Consumerism, shown here as a showcase of hats in the store played out delicately like a field of poppies that Cléo stares at with wonder.

Beauty standards, demonstrated by Cléo’s close relationship with a model who tries over and over again to tell Cléo that “my body makes me happy, not proud.” Aging, as a taxi cab parked directly in front of horse spring riders at a playground.

Unfortunately, Cléo has no clue yet about these systemic instruments that silently do violence to her every day. But a series of chance encounters from 5:00pm – 7:00pm to boost her mood a little bit— and maybe that is more important for her than anything else. Cléo from 5 to 7 is socially resonant today in ways that the landmark films of many of her male contemporaries simply are not.

Available on Kanopy.

3. The Servant by Joseph Losely (1963)

United Kingdom, British New Wave

Before the 60s in England started to swing and The Beatles, Kinks, and Stones came stateside to have their own New Wave, directors including Tony Richardson, John Schlesinger, and Joseph Losey took what they were seeing at the Royal Shakespeare Theatre, lit it on fire, and put it on screen. Responsible for inventing the “kitchen sink realism” that pioneers from the states like Sidney Lumet and Elia Kazan quickly adopted, the British New Wave focused on real working class people going about their everyday lives.

Previously, English films only included working class characters as clowns. The New Wave directors made films that pointed out that any ignorances on the part of these “angry young men” were built into them by a society that forced them to work in the factory all day.

The Servant, adapted by Harold Pinter from the novelette by Robin Maugham, follows Tony (James Fox), a young Londoner who seems to fit perfectly into a contemporary archetype familiar to us in the United States: the white man who does barely any work as a “developer” (colonizer) in other countries (in this case, Brazil), without any thought of consequence, and makes enough to live a very posh lifestyle doing so.

An accessory of this high life is servant Hugo Barrett (Dirk Bogarde), who is the cook, maid, interior decorator, and alarm clark in Tony’s decadent home. From early on in the film, when Tony and his fiancé Susan (Wendy Craig) try to speak in private, almost overpowered by the sound of screaming children at play outside, it is made clear that this is a film about a set of characters’ relationships to those removed from their world. Also early in the film, it is made clear that International Mogul Tony can not really make the bed, let alone do anything good for Brazil.

Frequently viewed through fun house-like bent glass mirrors and banisters that act as bars, Tony is distorted and caged, a pure product of his imperialist class-obsessed society. Here, we go beyond the working class “angry young man,” which is definitely represented in a fashion by Hugo, to get to know the other side of the spectrum, “coach potato power-mogul” (new term): Tony.

Throughout the film, Losey’s direction proves confident in comedic and dramatic venues, as the power dynamics within the household see-saw through a carnival of twists that would be cruel to spoil.

This is a film where no one comes out the hero, each character marked by his / her tiny gestures of privilege. Full of comedic bravura and sharp commentary, unwilling to fit into any particular package, The Servant is as much a precursor of post-Wave films like A Hard Days Night as it is Ken Loach’s oeuvre.

Available to rent on Amazon.