Like music, like painting, like all the other arts, cinema in its artistic form has been looking for its own essence since its beginning, and hasn’t yet found a definitive, fixed one. We could say that its very essence is to look for that essence, through all the possible combinations of its components (sound, silence, image, color, editing…). When it is art and not merely entertainment, cinema is always experimental, because it searches the right way to convey exactly what each film struggles to say.

Throughout the history of cinema many directors have tried to find their precise way of treating films, ways that weren’t just aesthetic options, but that were closely linked to ethical standpoints. Art is never for art’s sake.

From this perspective, it is possible to pinpoint some very special films that managed to create a meaningful form that transformed deeply the way we understand cinema. They broadened our understanding of cinema as art. When they were released, they were difficult to grasp, and many were misunderstood and undervalued. Since they were so new in different aspects, critics and viewers needed some time to assimilate them.

This newness hasn’t anything to do with spectacular technique. Nowadays, when 3D and all the possibilities made available by computers are so easy to use, we value more than ever the sheer reflexive, poetic films.

Fortunately, cinema has provided us with many films of this essential cinema. Let us talk about some of them.

1. The Passion Of Joan Of Arc (Carl Theodor Dreyer, 1928)

Many films have been made about Joan of Arc, the French martyr and saint burned at the stake by the catholic church and the English in 1431, beatified in 1909 and canonized in 1920. We can mention, as the almost best, the renditions by Rossellini (1954, with Ingrid Bergman) and Bresson (1962). But the one that comes to mind to any cinephile is the silent film by Carl Theodor Dreyer, a landmark in the history of cinema, and one of the best films by the Danish director, along with The Word (Ordet), Vampyr and Gertrud.

The reasons why this film is so unforgettable are artistic, but they go beyond the mere technical aspects. Dreyer (who was given by the producers the option to choose a historic figure as a subject-matter of his film, and apparently chose Joan of Arc because of her recent beatification) wanted to show the plight of a being of flesh and blood facing the cruelty of her sadistic accusers in a trial for heresy.

He eschewed making a celebratory film, a heroic biopic or nationalistic propaganda, and decided instead to show the suffering of an individual person in her commitment to her religious faith, despite psychological and physical torture. The film is often qualified as transcendental, and it is rightly so, as long as we don’t forget its deep human concern.

Dreyer managed his artistic goal by destroying conventional ways of filming and by creating a new cinematographic writing. Whereas the overall narrative is chronological and linear (although the 29 days that lasted the historic trial are condensed in just one), images are worked to show the inner life of Joan, played by a memorable Renée Jeanne Falconetti.

Here I merely mention, without explaining, the main features of this new cinematographic style, that ninety years after the release of the film are still as revolutionary and compelling as the first day: the foremost, the extreme close-ups of the human face, especially that of Falconetti, of course (landmark images of all the history of cinema), but also of the sinister faces of the clergymen and the English governor who judge her.

Expressionist low-angle, inverted shots, that reflect the anguish of Joan. Broken composition, lack of continuity between shots that stress the existential loneliness of Joan. Erased depth of field and perspective that increase the intense effect of the close-ups, bringing the faces to the foreground.

All this options, combined, create an intense effect of human plight and spiritual struggle that have remained deeply fixed in the minds of cinema-lovers.

2. Vivre sa vie (Jean-Luc Godard, 1962)

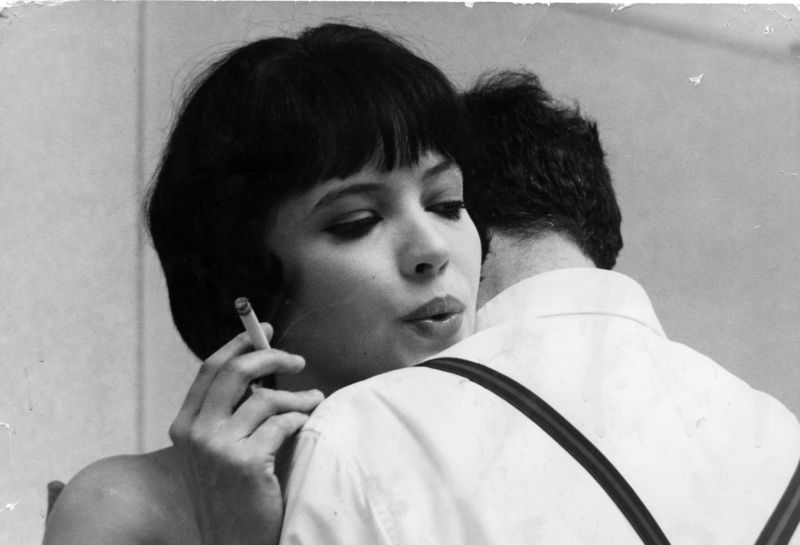

Nana (Anna Karina), a young Parisian, sees Joan of Arc-Falconetti at the cinema and decides to follow her example and fulfil what she feels as her destiny. She quits her husband and her little child to becomes an actress, the dream of her life. But things won’t go as desired and she will end up being a prostitute in the hands of pimps, and killed in a gunfire.

The film reflects the problem of prostitution in Paris, criticizes consumer society and the commodification of women bodies. But he treats viewers as grown-ups, and avoids delivering an edifying lecture. He uses many alienation techniques to prevent spectators from getting leisurely involved in the, to remind them of their role as moral consciousness that observe and must decide about what they see.

Some of the techniques displayed are the ostensible division of the film in 12 tableaux, the use of intertitles that announce what will happen in the next episode, an edition that breaks narrative apparently seamless flow, the shooting of characters from behind even when they are talking, in a way that hides their faces, comments on social issues by a voice-over…

On the other hand, the film goes beyond all the social questions it raises and shows us the naked soul of a woman. The face of Anna Karina, like that of Falconetti, conveys with an unforgettable intensity the inner life of her character, the nuances of her moral decisions, her determination of living her life.

This is why we don’t feel sorry for her, even when she encounters the worst difficulties: we understand that she must face all the consequences of her decision to reach her inner truth. The artistic miracle of this effect -stronger and stronger with each viewing- is created both by the acting of Anna Karina and the way Godard (by time her loving husband) manages to film her face.

3. Persona (Ingmar Bergman, 1966)

Ingmar’s Bergman masterpiece (without forgetting The Seventh Seal and Wild Strawberries, of course, and some will add Through a Glass Darkly, The Silence…) has troubled critics and spectators alike since it was released. Almost plotless, with many cryptic images and apparently unconnected events, it resists any summary or definitive explanation.

What can be surely said about Persona is that its main characters are the actress Elisabeth Vogler (Liv Ullman) who went silent when acting Electra and hasn’t talked again for months, without anyone knowing why, and the nurse Alma (Bibi Andersson), in charge of taking care of her and of trying to help her to recover.

A large part of the film consists of both of them interacting in a very strange relationship: Elisabeth closed in her hermetic silence, and Alma talking to great extents, until she reveals secrets and traumas she would have preferred to keep to herself. Elizabeth’s strong will and determination undermines Alma’s delicate, weak personality.

As we don’t know why Elisabeth keeps silent, we struggle to understand the sense of the film. Is Elizabeth speechless because of the horrors of our world? Does she represent the impotence of art to say anything significant to our existence? Or even, should we understand the film in a symbolic perspective and see Elizabeth as our deepest level of consciousness, and Alma as an attempt to express and reach the other (the Other)?

If the close-ups of Falconetti’s and Anna Karina’s faces have remained as iconic moments of cinema, close-ups of Ullman and Andersson have become so, too. Especially the ones of Ullman, so close, so intimate, so personal, that they almost hurt. The final, interlinked close-up of the faces of both actresses seems to suggest that their personalities merge into one.

The mystery of this avant-gardist film (the most artistically radical by Bergman) is stressed by images that are more than cryptic: they just don’t make sense. The Swedish director and his cinematographer, Sven Nykvist, made a very original use of black and white, with lights and shadows that become part of the argument and a dimension of both personas, and that stress the deep effect caused by the close-ups.

4. Au hasard Balthazar (Robert Bresson, 1966)

Probably the best film by Bresson (although one should bear also in mind A Man Escaped, Pickpocket and L’argent), Balthazar shows the French director’s original language at its peak, a mature style that had consolidated through two decades.

The film tells the story of a donkey that stays with many humans and is able to see the evil that pervades our world. Most of his owners treat him with cruelty, beat him and starve him, and he keeps staring at all this callousness with a serene impassibility.

Balthazar is shown as a martyr, as a saint. Bresson (a catholic believer) gives him a Christian sense, even creates a Christ-like figure, in his resistance, pardon and agony. The donkey sees the evil in human nature and withstands, seems to forgive it. With his passage through human world, he redeems human evil.

The destiny of Balthazhar is linked to that of Marie (Anne Wiazemsky), a peasant girl that knew and loved him as a child, and that loses her purity because of the same human cruelty that abuses the donkey. Both suffer the sheer callousness of the same people, but Marie choses to sink in sin and evil, and after being almost raped by a wrongdoer, she abandons herself to the gang of rogues he leads. In spite of all this, we feel she has kept, very hidden, the integrity of her soul

Bresson conveys his understanding of our vicious world through his distinctive ascetic directorial style, naturalistic and minimalist. He casted nonprofessional actors and made them act in a deliberately inexpressive fashion, to create a characteristic realism that doesn’t affect sensibility directly, but that first crosses the mind.

He made abundant and very significant use of ellipsis, that is, the device of not showing scenes and leave the spectator to imagine them, which in Bresson has a stronger impact than if the scenes were seen. Similarly, he avoids general composition and prefers displaying just isolated parts -a hand, a leg- leaving the rest offscreen.

5. Last Year at Marienbad (Alain Resnais, 1961)

Resnais’ Marienbad puts the artistry blatantly in the foreground and impedes any emotion, bringing the viewer to a philosophical field where what counts is the question about the literal (not moral) sense of the film.

The glacial story is set in a luxury hotel, where a man and a woman (nameless) ask themselves if last year they had an affair in the same scenery, and a second man (maybe the husband) takes part in the debate as a minor character. The same or very similar questions are made once and again to try to make sense of what happened last year at Marienbad, but nobody seems to be able to understand their memories, or to make them coherent, to articulate them.

The first man claims that he and the woman started an affair and that she decided to take a year to think about their relationship, the woman denies it, while the hypothetic husband makes himself present through his playing a table game against the hypothetic lover.

Assertions, refutations, questions, doubts are refashioned and repeated by voices over while we see the long corridors and large rooms full of mirrors of the baroque hotel, the geometry of its rococo gardens, and we are kept ignorant of what is happening, or happened.

Among the viewers who enjoy the film in a philosophical manner, there have been many renderings: that all the dialogues (or parallel monologues) take place inside the woman’s (or man’s); that it is an interchange between a psychoanalyst and his client or that all is a dream (or a dream inside a dream, like Russian dolls) or that everything consists of a ghostly conversation between disembodied souls. One can add many alternative interpretations.

In any case, they can agree that the film problematizes all the structures we tend to take for granted in order to lead a reasonable life: the unequivocal flow of time, the stability and reliability of our memories, the one-sidedness of our personalities.