Movies can be a gateway in many ways where we can include our own history. Sure, we can listen to music from specific times or see paintings from centuries ago. However, film can bring the past to life in all of its elements. Therefore, here are 10 films that make us change the way we see history.

1. 12 Years A Slave (2013) – Steve McQueen

There have been films and miniseries ranging from “Roots” to “Django Unchained” to even elements in “Gone with the Wind,” but with Steve McQueen’s third feature, we get the most brutal and honest depiction of slavery in the United States circa the 1850s.

The film continues McQueen’s approach in combining brutality and a difficult subject matter to artistic prowess in cinema. Here, we follows Solomon Northup’s journey, played with heartbreaking realism by Chiwetel Ejiofor, from free man to slave in the deep South.

The film is episodic in nature that shows the auctioning, transportation, living and working conditions, and psychological trauma that slaves went through. All of this is based off of Northup’s own book upon which the film is based – it is literally a first-hand experience.

While being a very difficult subject matter, McQueen manages to find beauty in the escape and search for freedom, whether it’s allowing the camera to linger on Ejiofor’s face, a choir chant, moments of grace with fellow slaves, and in this case and depiction, human beings like any other.

No film before or since has captured what this life could have been like for a person of black or brown skin in pre-Civil War America. Regardless, we will never have to see another film to show the horrors of slavery even as McQueen found a brutal, harsh truth and made an incredible film out of it.

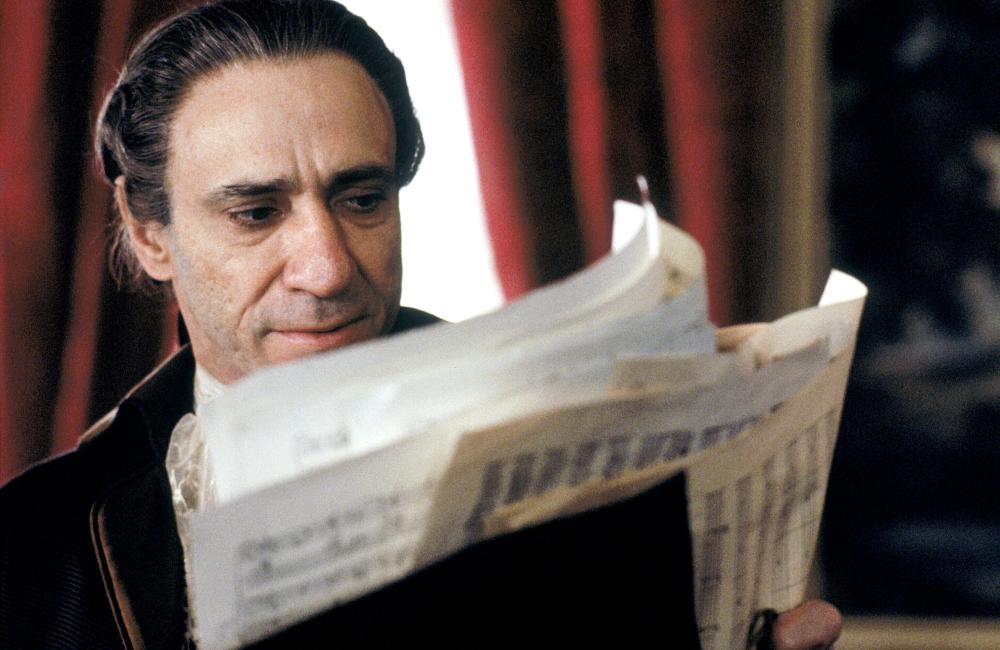

2. Amadeus (1984) – Milos Forman

When it comes to opera or classical music, many people think of English aristocracy or dry films where the costumes and set pieces are the main attraction. Not so much the case when Milos Forman brought Peter Shaffer’s play to the screen.

Of course, the film is gorgeous to look at with all the grandeur set design, costumes, wigs, makeup, and so on, but the atmosphere, mood, and persona of the character, particularly Tom Hulce’s Mozart, make us see Vienna in 1770s a bit differently.

As the film unfolds via flashbacks from F. Murray Abraham’s Salieri, filled with affection, rage, and jealousy, we not only witness Mozart’s genius but his own inner conflict of acting with an obscene, party-going, childlike manner.

The only time we’ve seen period pieces with comedy or wit, such as “Tom Jones” or any Sacha Guitry film, have been traditional faces or satires, but here, Forman was showing what actually occurred, but bringing a liveliness to it that we’ve never seen.

The film can be seen as an inspiration for another period classics with a unique spin, such as Sofia Coppola’s “Marie Antoinette,” because it showed us classical figures acting, behaving, and speaking in modernity, and most importantly, we relate to Mozart and Salieri on human feelings and behavior and not as a painterly figuring occupying a pretty canvas.

3. Gangs of New York (2002) – Martin Scorsese

A film that Scorsese wanted to make since he was a film student as NYU shows how much he was thinking about this throughout his filmography and life. However, the film is composed of historical gangs from around the city of New York, but the devil is in the details with all the surrounding components.

The film touches upon the slum life in New York between 1846 and 1862 during the Civil War, the corruption of William “Boss” Tweed and Tammany Hall, Irish immigrants, to the notorious draft riots toward the end of the film. But instead of presenting a historical film in documentary fashion, Scorsese uses the story of a boy seeking vengeance for his murdered father as he infiltrates and gains the trust of the man who owns the Five Points.

Crafting a stellar cast and typical story allowed Scorsese to explore a world and atmosphere that we’ve never seen before. This is a radical departure from his own “The Age of Innocence,” also starring Daniel Day-Lewis, because aside from a few scenes, we can actually see what life was like on the streets.

Of course, Scorsese received some criticism, such as the use of Chinese-Americans or the actual importance of Tweed in the development of the city, but he and his team literally created a world (in Cinecittà in Rome) that we’ve never seen.

4. Apocalypto (2006) – Mel Gibson

A film that has never before or since explored the Mayan civilization as in Mel Gibson’s native language chase of a film. Composed entirely of regional non-actors and shooting in digital format, Gibson created a film with modern technology exploring an ancient civilization in the early 1500s in Mexico.

The film is rather simple as a young man is literally running for his life and trying to get home, in which he enters a kingdom on the verge of decline composed of sacrifice, horror, and ritual.

As the film progresses, we see more and more of what Mayan civilization could have been like. Scholars and critics felt it was as accurate as possible according to ancient paintings and drawings (as presented in the film as well), and the overall aspect of the civilization’s peak to its eventual dealings with the New World.

One of the most eye-popping visuals in the use of human sacrifice in the film. As this scene unfolds, we must simply give ourselves over to what seems to be a historical representation of beliefs, rituals, and customs for thousands of years. Not necessarily abandoning narrative, but Gibson managed to show us something we’ve never seen and no filmmaker has dared to since.

5. The Battle of Algiers (1966) – Gillo Pontecorvo

A film that could be easily mistaken for a documentary as the film begins but transgresses into something personal, scary, and relevant even today. Pontecorvo shot this film in a detailed documentary-like fashion that showed native Algerians fighting for their independence against the governing French.

As the film chronicles the daily struggles, down to the nitty-gritty real-life struggle, we start to see insurgency in a different light. Here is a nation of people that simply want to live their lives according to their cultural, religious, and social doctrine, and not be interfered with from colonial powers.

One must think of this in terms of later conflicts, such as the English in Northern Ireland or American forces in Iraq, or even the pilgrims coming to the American continent in the 1400s. This film shows the people conducting insurgent operations not out of terrorism, but as a fight for freedom.

The film was banned in France for five years and has only been screened after the conflict ended in 1971. The film is still a cinematic reference for this type of campaign, but also in terms of cinema as it is a gripping and even experimental docudrama approach. It is scary to think that after 50 years, this film is still relevant and alive, and continues to make us look at our present-day timeline differently through films of the past.