If the crucial encounter between Jack Nicholson, the star of “Chinatown”; Robert Towne, the screenwriter of the film; Robert Evans, the influential Paramount producer; and last but not least Roman Polanski was featured in Paolo Coelho’s book, it would be dismissed with terminal condescendence by all critics. It would no doubt be considered either some blatantly manipulative ”feel good” fantasy or a case of already clinical delirium. And yet, Nicholson and Towne were close friends and roommates for a number of years in Los Angeles, while Evans happened to be a mutual friend of both and also had a friendship with Polanski, who was living in Rome at that time.

Evans proposed to Towne to write an adaptation of “The Great Gatsby,” but eventually they ended up talking about a larger-than-life story of corruption during the severe drought in Los Angeles in 1910. Towne heard the story of a massive water scandal during the drought, from his father. However, when Evans invited Polanski to Los Angeles to talk about it, they decided to move the story in mid-to-late 1930s.

1. A catchy premise

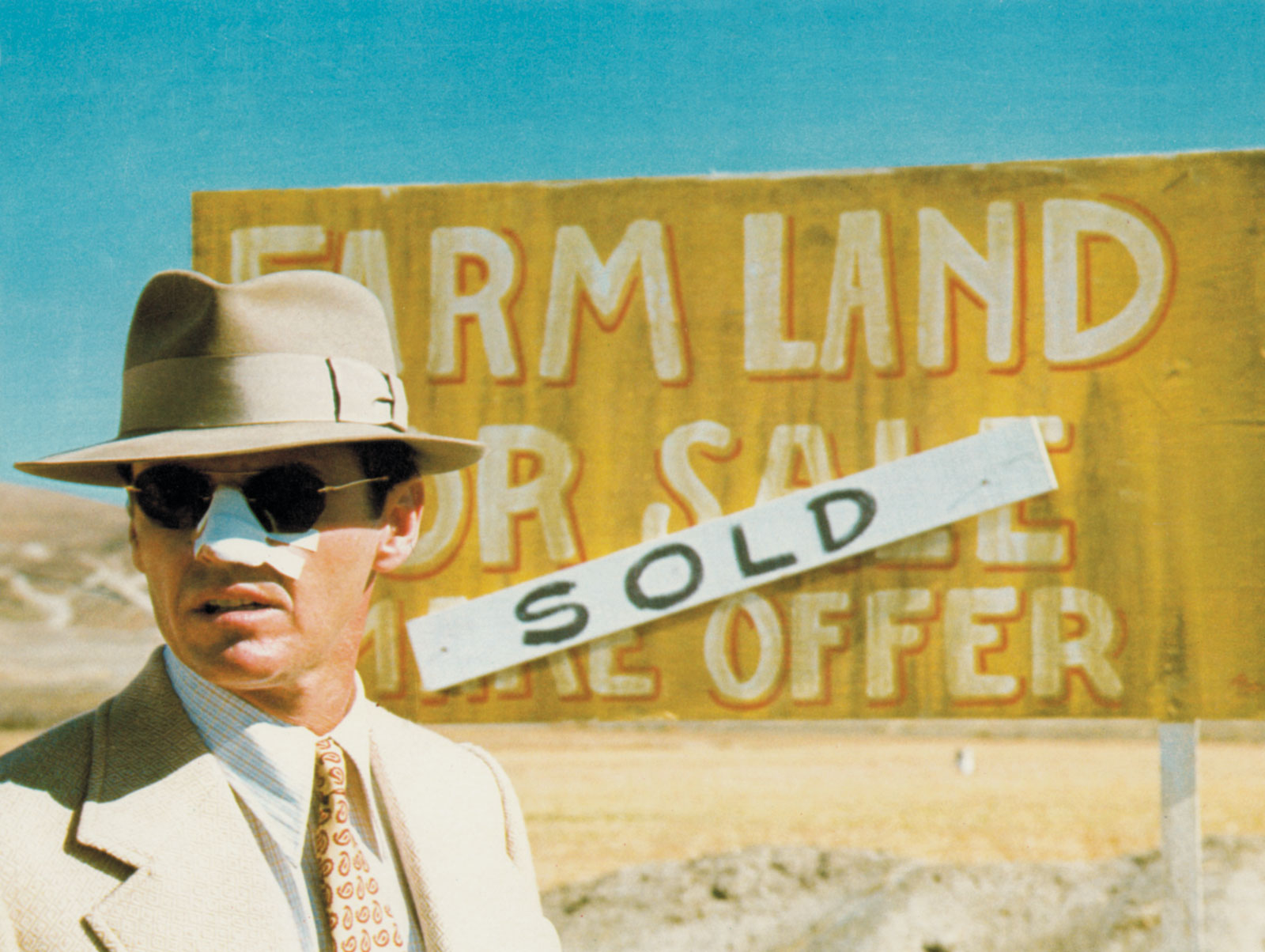

A cool and nonchalant detective in 1930’s Los Angeles finds himself, upon pursuing a routine investigation, in the midst of an ultra-complex corruption scheme involving greed, fake contracts, and assassinations.

The protagonist is a likable and charismatic but morally ambiguous character that is a perfect stand-in for the audience.

2. Amazing architecture of vision – the script

Jack Gittes, a charismatic and moderately successful detective, is hired by a rich woman, Ms. Evelyn Mulray. for what seems to be a routine investigation of an extra matrimonial affair.

Soon enough, Gittes finds that the woman that hired him is not who she pretended to be. The real Evelyn Mulray turns out to be not only rightly perplexed, but determined to sue the protagonist.

Interestingly enough, Evelyn turns out to be the wife of the recently deceased chief engineer of the water and power company in Los Angeles, which had just been involved in a corruption scandal.

Intrigued and also hurt in his pride for having been manipulated for reasons that he simply can’t even begin to understand, Gittes decides to further investigate the matter. Trivial infidelity or not, the husband of the real Evelyn Mulray seemed to have had an extra matrimonial affair.

Even more intriguing, Hollis Mulray is also at the heart of a major controversy; he refuses to build a dam that would serve the interests of several powerful and rich people in a complex real estate scheme to appropriate cheap lands affected by drought in the San Fernando Valley. Once the lands are incorporated into Los Angeles, the plan is to “suddenly” irrigate them through the dam, and in doing so, immediately explode their commercial value.

A little bit of Los Angeles history might be crucial here to grasp this part of the plot: A similar dam was built in Los Angeles in 1929, but the construction plans were so bad and the capitalist greed was so huge that the dam failed and flooded, killing hundreds of people in the Santa Paula area.

However, Hollis reveals at a public hearing that the plans for the dam are so bad that, “It won’t hold. I won’t build it. It’s that simple. I won’t make the same mistake twice.” While in court, Gittes notices Hollis’s guts and integrity.

Shortly after, Walsh, one of the protagonist’s two assistants, shows Gittes pictures of Hollis fighting with an older man. Walsh, hidden in the distance, is able to intercept only one word: “Applecore.”

When Hollis Mulray turns up dead – drowned in the middle of a drought – Gittes’ nonchalant and sardonic demeanor starts to deteriorate, as for the very first time in his career, he is involved in something that is above and beyond a routine extra matrimonial investigation. It actually has an unprecedented conspiracy magnitude and it could also possibly have life-threatening consequences.

When he meets Evelyn’s father, Noah Cross, the patriarch of greed and corruption in Los Angeles, Gittes not only finds out that he is the co-owner of the water and power company in Los Angeles, but he also entertains the elite at an upper scale nautical club called Albacore.

Jack Gittes is hit by a massive revelation: “Albacore” sounds suspiciously close to “Applecore,” the word overheard by Walsh during Hollis Mulray’s fight with the mysterious old guy.

Another ominous detail is that the powerful magnate in front of Gitte seems to resemble the guy fighting with Hollis in the picture captured by Walsh. Well, at least as much as the limited visibility during the night conditions allow for a credible identification. And once again, the picture was taken the night before Hollis turned up dead.

Jack Gittes is in every scene of the film. The audience never knows more than the protagonist, following viscerally Gittes’ tribulations of uncovering a conspiracy involving the highest levels of power and business, and also his gradual frustration when he understands that the nefarious Noah Cross is beyond accountability.

The antagonist owns the city; the water and power company, the land, most of the press, multiple companies, and several judges are “in his pockets.”

It’s a very smart concept as the audience follows the gradual uncovering of the ultra-complex and completely credible scheme of corruption by the detective who’s smart and also cynical about human nature (although still pretty humane, as demonstrated by offering his initial client a glass of whiskey and a discount).

If the character of Jack Gittes were a Voltaire-like “ingenue,” or God forbid a “fish out of water” comedic character, the film would have been obviously a camp type of comedy, tone-wise. The audience needs to identify with a protagonist that posses credible empathy, even if his morals are somewhat questionable.

The fact that “Chinatown” has a very confident protagonist – almost to the point of cockiness – allows for a very ample and nuanced character arc as Jack Gittes descends slowly into perplexity, frustration, and finally existential resignation.

3. Jack Nicholson and Faye Dunaway – top artists at the service of the story

Both actors earned nominations Oscar nominations for their performances in “Chinatown.”

While Faye Dunaway surprisingly lost to Ellen Burstyn for Martin Scorsese’s “Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore,” how Jack Nicholson didn’t take home the Oscar for his earthy and nuanced performance in “Chinatown” performance is downright bizarre.

Dunaway had already been nominated for an Oscar for her amazing performance in “Bonnie and Clyde” in 1967, but Jack Nicholson had practically “subscribed” to Oscar nominations, even before the lead role in Roman Polanski’s masterpiece, as he collected no fewer than three nominations in the four years prior to “Chinatown.”

Two of Nicholson’s nominations were for Best Actor in a Leading Role (“Five Easy Pieces” in 1970 and “The Last Detail” in 1973), while the first Oscar nomination in his career happened four years prior to “Chinatown” (Best Actor in a Supporting Role for “Easy Rider” in 1970).

The protagonist’s role in “Chinatown” was written, as per Robert Towne’s own statements, with Nicholson in mind. The ample character arc, from a sympathetic and charismatic but somewhat cocky, morally questionable detective, to an increasingly frustrated character, is very nuanced and extremely well-calibrated.

The next stage, from the impotence in exposing the crimes through any legal channels and actions, to existential rage and ultimately resignation (“Forget it, Jake, it’s “Chinatown”) might have been handled with some degree of histrionism and cheap tricks, such as raising the volume of his voice and using tortured grimaces by a lesser actor.

Nothing of that sort with Jack Nicholson.

He covers a wide range of emotional states and moods – a cocky attitude and sardonic humor with his two employees and some of his clients; impatience with the Chinese gardener’s accent; gradually falling in love with Evelyn Mulray yet dissimulating his true feelings; being completely repelled but also professionally intrigued by the terminal corruption and ruthlessness of Noah Cross.

Dunaway, despite reports of bitter complaints with Polanski’s handling of the actors on the set and radical disagreements, manages probably the best performance of her career as the vulnerable, neurotic victim of her monstrously abusive father, hiding behind the facade of a mysterious and capricious upper-class femme fatale.

A phenomenal pair of actors for the lead roles of an amazingly complex and compelling script.

Jack Nicholson ended his no-win streak just two years later in 1976, for Milos Forman’s “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.”

4. Roman Polanski’s tragic vision subverts and transcends the neo-noir conventions

All directors working from the 1960s on in any neo-noir picture were hyper-aware of the genre’s thematic and aesthetic conventions.

First of all, an urban story of terminal corruption unveiled by a detective, and the inevitable presence of a femme fatale (up to a certain point, at least, as Evelyn emerges ultimately as a tragic victim) seems to place Polanski’s film into classical noir territory.

And certainly, on a thematic level, it is.

The aesthetics, though, couldn’t be more opposed to the extreme contrasts between well-lit areas and dramatic and expressionistic shadows. There are no twisted Dutch angles and no distorted Jeunet or Kubrick-like POV shots; such as those in “Dr. Strangelove,” taken with wide-angle lenses indicating the character’s mental imbalance.

Polanski’s clinical and highly intelligent mise en scene and John Alonzo’s glossy lightening have a nostalgic tone, supported also by the haunting, romantic score written by Jerry Goldsmith.

Polanski also brought his artistic DNA to the narrative. Robert Towne envisioned a story of the incredible magnitude of corruption that we have in “Chinatown,” but strange enough, with a happy ending. In Towne’s first drafts of the script, Gittes was able to finally expose the conspiracy, survive and live happily ever after. But Polanski certainly did not see it that way.

The nefarious Noah Cross, representing the self-entitlement of the super-elite that considers themselves above and beyond the law, is able to get away with real estate colossal scams, the rape of his own daughter, murder, and quite mind-boggling levels of corruption.

The first major disagreement between Polanski and Towne was about the ending. Towne found Polanski’s ending bleak and “too tragic for his own taste,” while Polanski felt the first draft happy ending envisioned by Towne was shallow and completely unrealistic.

The second major disagreement was about whether the protagonist was going to sleep with the icy blonde portrayed by Faye Dunaway. Towne was against it, while Polanski felt that in the noir tradition, Evelyn must seduce the detective and add another layer of complication to an already tough investigation.

However, this as far as the noir genre femme fatale (deadly woman) convention goes.

In the famous and disturbing scene where Jack finds out that Katherine, Evelyn’s daughter, is also Noah Cross’s daughter; and that the evil antagonist raped his own daughter, causing her to run away from home when she was 15, the apparent icy and manipulative femme fatale image of Evelyn is all but shattered. She is revealed simply as another tragic victim of her diabolic father.

Also, another subversion of the noir genre about which Polanski was crystal clear from the beginning was that most scenes would occur in plain daylight, and not in dark and claustrophobic environments.

The last scene of the film, where Evelyn is shot dead by the police officer when trying to run away with the girl, is shot on location in LA’s Chinatown. After the public illumination system was significantly altered to give it an authentic 1930’s feeling, the scene was treated by Polanski in an almost documentary style.

We see the officer shooting in the direction of Evelyn’s car; another guy stops him, at which point a colleague pushes forward and resumes shooting. The car stops and honks, at which point we know Evelyn must be dead, with her head collapsed onto the horn.

A fast whip pan connects the detectives and cops shooting with the scene of the tragedy. Evelyn lies dead while her daughter screams in panic and despair. A detective lifts up Evelyn’s body, while Noah Cross closes Katherine’s eyes and takes her away.

The implications are downright macabre – the incest cycle will repeat itself and the life of Katherine will also be destroyed.

There is another, much slower pan left ending on Gittes, who whispers to himself as if in a trance, “As little as possible,” an abbreviated form of the professional mantra we heard before, “Do as little as possible.”

“Don’t interfere with the crimes and corruption of the elite if you want to stay alive” is what Towne repeatedly heard from a Hungarian cop who was working on cases in Chinatown.

Sobering, but honest beyond reproach.

5. A romantic and haunting score by Jerry Goldsmith

The amazing thing about Jerry Goldsmith’s intoxicating score for “Chinatown” – which also earned an Oscar nomination – was that it was written in only 10 days. He was brought in to “rescue the film” after the first score was rejected.

Robert Evans suggested a kind of music that is authentic for the 1930s, but Goldsmith instead persuaded the producer to go for something timeless, as the characters’ emotions transcend a specific time period.

From the title credits, we hear a haunting and intoxicatingly melancholic tune running over a yellowish-ochre color scheme, perhaps subliminally suggesting a dry and arid landscape.

As opposed to many didactic and manipulative scores in Hollywood that indicate or even impose on the audience what they must feel in a scene that doesn’t elicit such feelings, Goldsmith’s classic score amplifies emotions that are already built in the scene through story, performance, and color scheme.

The Oscar for Best Original Score, however, was won that year by another extraordinary composer: Fellini’s lifelong collaborator, Nino Rota for “The Godfather Part II.”

6. The theme – darkness to be found not in the film’s aesthetics, but at the core of human nature

When the protagonist finally unveils a real estate massive scam – covered with blackmail, fake contracts, and ultimately the assassination of those opposing it (Hollis Mulray is killed, while Jack Gittes is threatened at gunpoint) – the theme of the film is catapulted on the screen through Noah Cross’s response to the protagonist’s question about guilt. “Most people don’t face the fact that at the right time, at the right place, they are capable of anything.”